The “governance” of cities may be narrowly focused on the way the local authority manages its organisational affairs, essentially the internal relationships between the council, political parties, and city administration. More broadly, “governance” needs to include management of the relationships the local authority has with external parties, including other government entities at the national, provincial, and local levels, and service providers active in the city’s functional area. The viability of the city as a place to live and work is fundamentally correlated with success in managing these relationships.

The extent of these external relationships also depends on how the “city” is defined, with the argument here that this should be taken as the functional urban area: the city and its commuting zone (OECD 2012), which can be approximated as the geographic area within the urban edge. As is evident from the case studies presented here, it is often the case that the functional area of the city spills over the primary city administrative boundary. This means there are multiple local authorities responsible for a single-city functional area, which creates considerable complexity in the planning and management of the city as an integrated urban area.

This leads to the primary argument in this article: that the success of cities as functional areas is promoted through having fewer institutions involved in both the management of the city and the associated provision of services to households and enterprises.

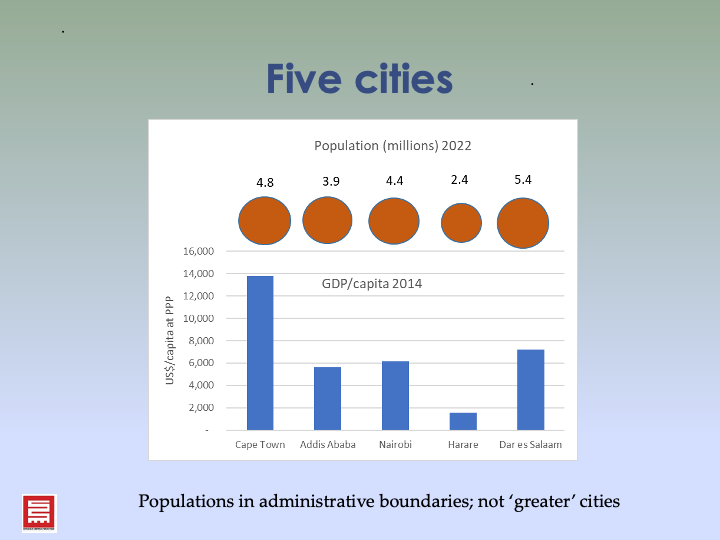

Five cities have been selected as case studies for this article as they are key cities in sub-Saharan Africa, they have differing institutional forms, and information on them was available to the author, based on work for the African Centre for Cities and the African Development Bank (AfDB). They have broadly comparable populations—although Harare is substantially smaller than the others—but very different economic circumstances, as shown in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1: Relative population and GDP per capita for five case study cities

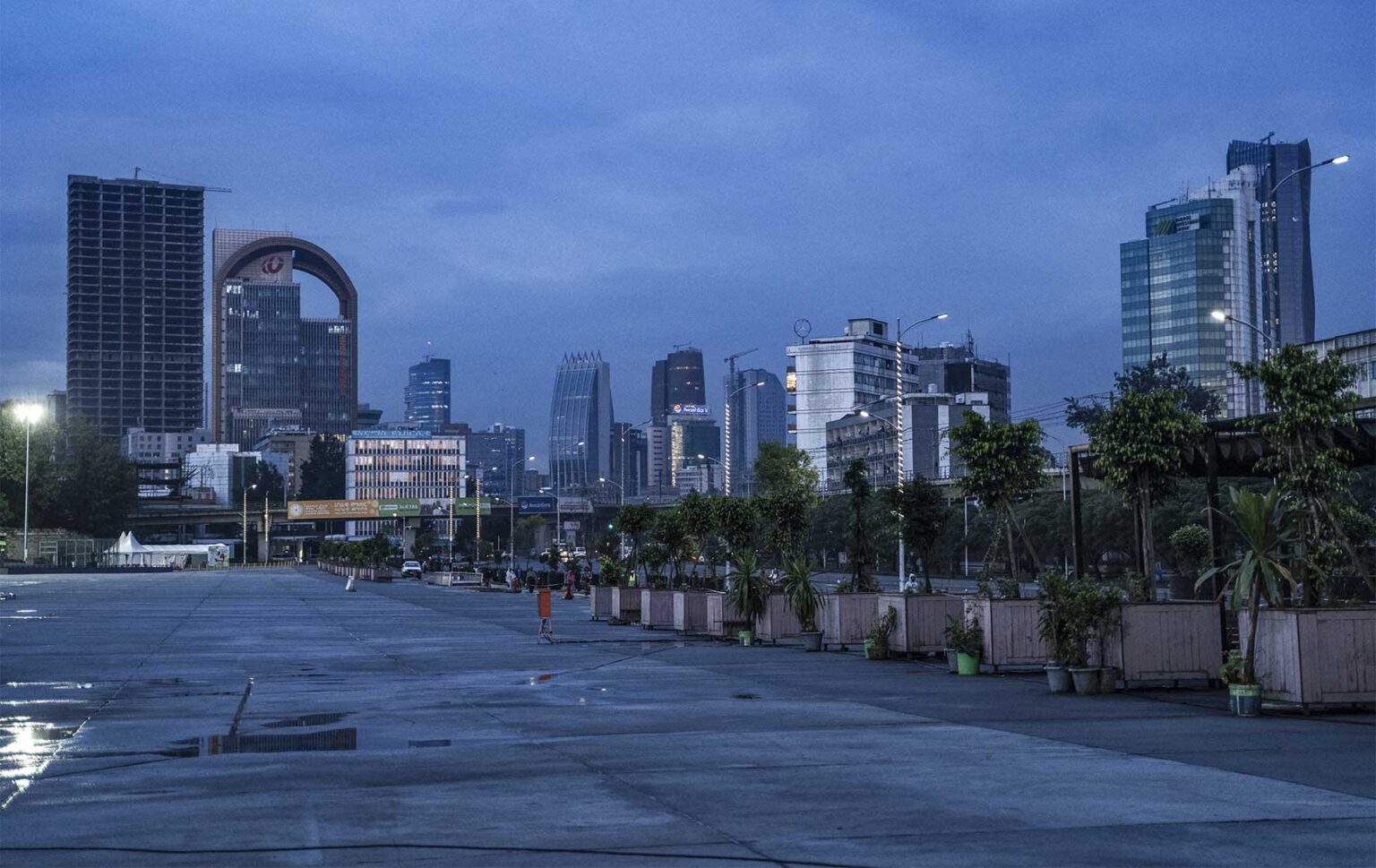

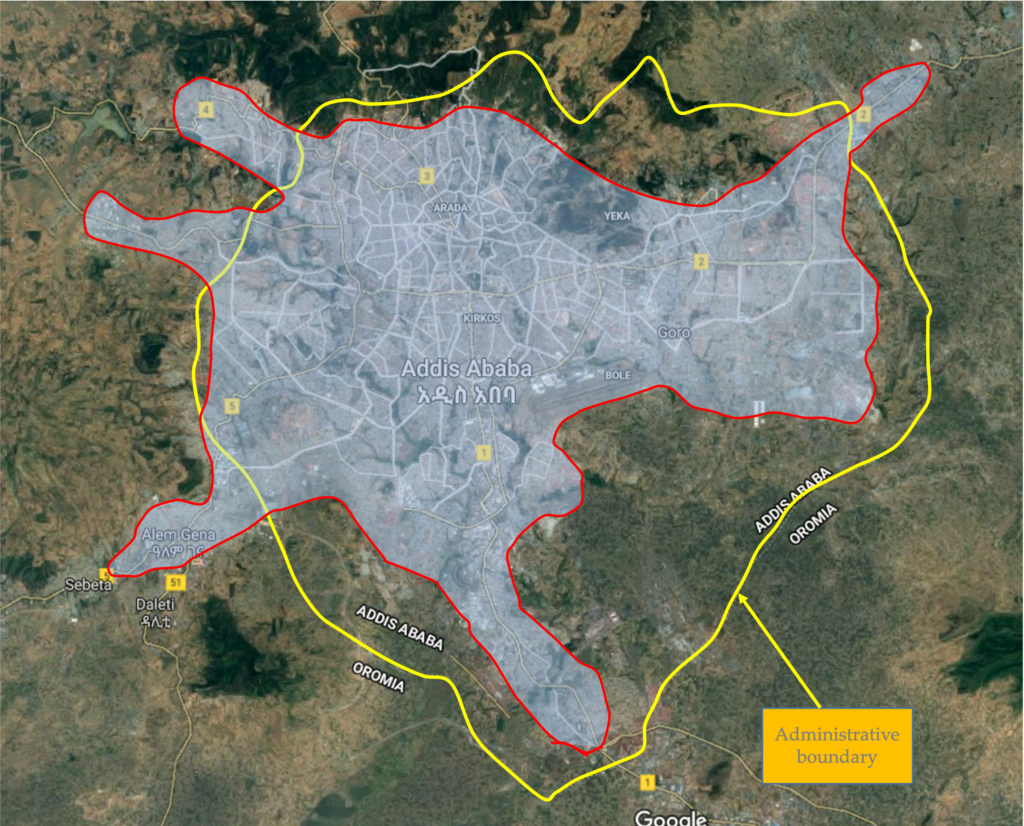

In the case of Addis Ababa, the Ethiopian government and Addis Ababa City are working towards densifying the city, with a focus on multi-storey residential complexes. Nevertheless, the urban area is expanding into rural areas outside the city boundary, particularly in the northeast, with expansion into the surrounding Oromia region. This is causing political difficulties with the Oromia people, as rural land on the periphery of the city is giving way to urban development in the Oromia region, which surrounds Addis Ababa.

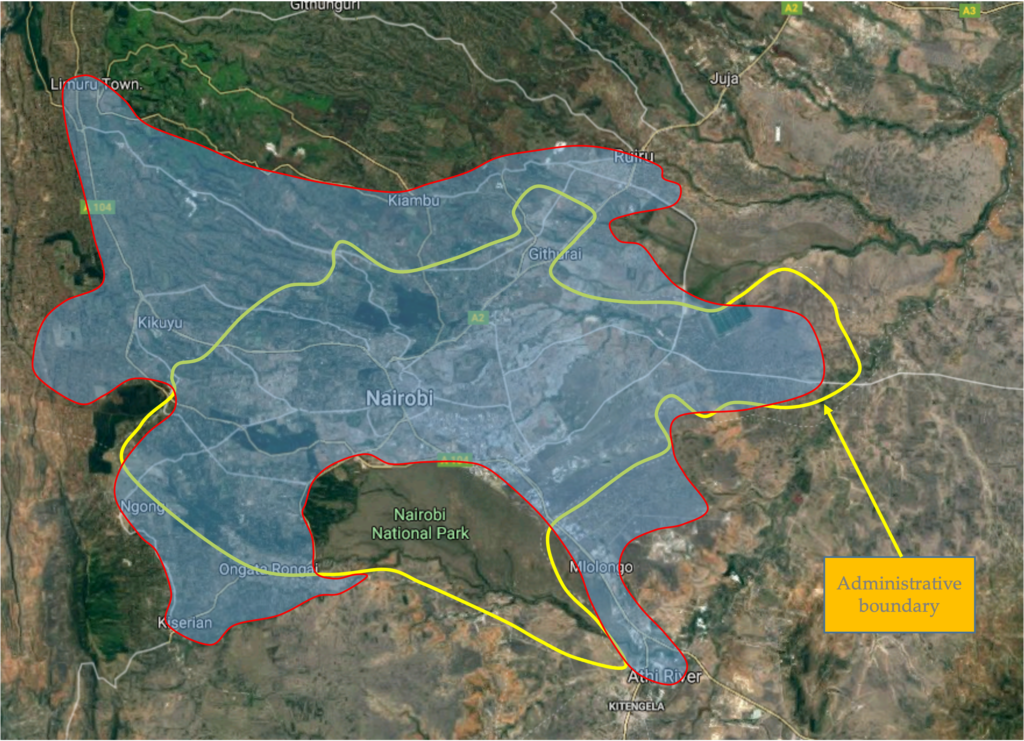

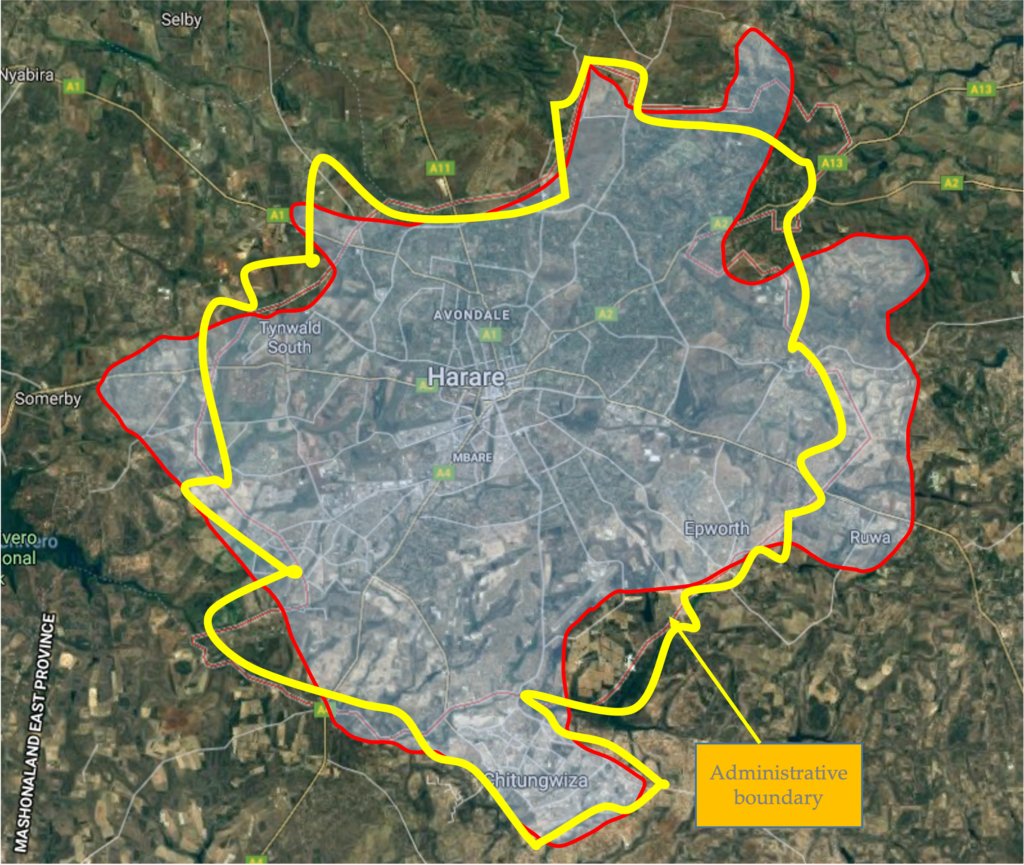

In Nairobi’s case, Nairobi County is the primary local authority serving the Nairobi functional area, but with three neighbouring counties, Kiambu, Kajiado, and Machakos, also administering parts of the area. City expansion is occurring in these neighbouring areas, which will result in increasingly fragmented city management, with water and sanitation services also affected as the counties own the water and sanitation companies. The functional area of Harare also spills over the administrative boundary of Harare City into neighbouring rural district council areas, notably Goromonzi, Chegutu, Zvimba, and Mazowe. The city also has three “urban” municipalities within its functional area: Chitungwiza and the Epworth and Ruwa local boards.

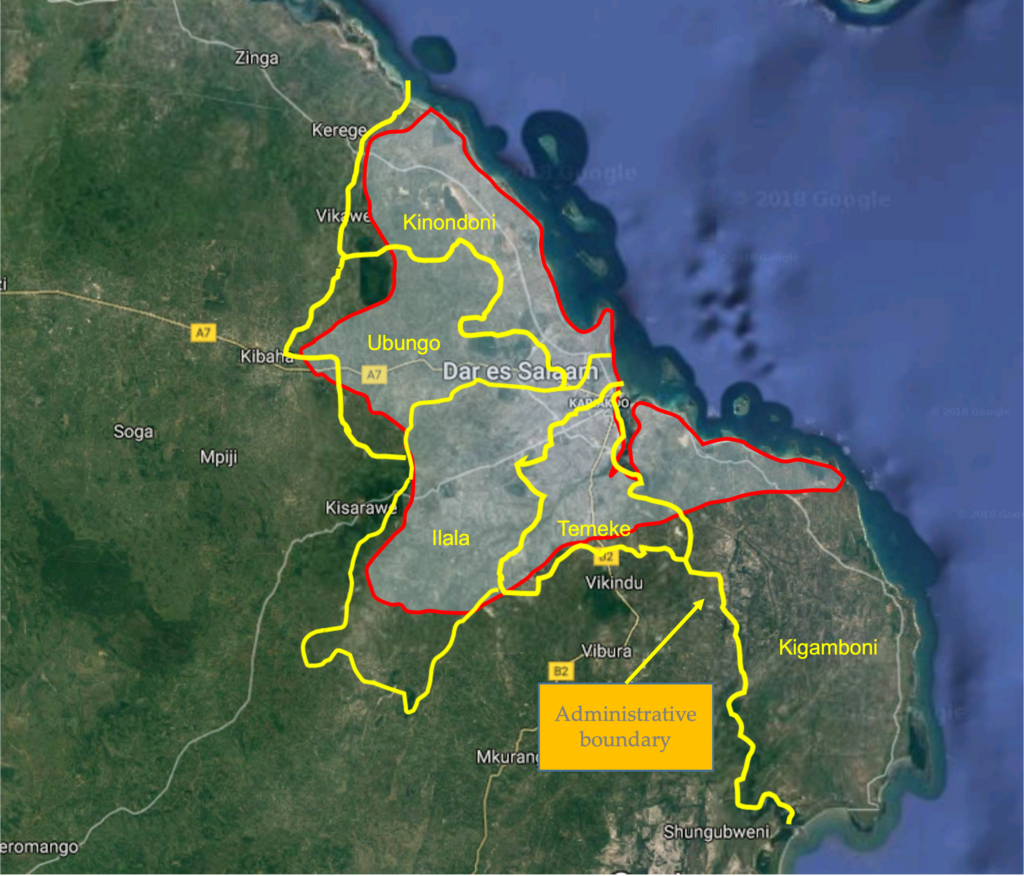

Dar es Salaam does not have this “urban overflow” problem as the functional area of the city is largely within the administrative boundary of Dar es Salaam city council. In this case, administrative complexity is created within the city boundaries due to five municipal councils being given greater powers and functions than the city council. Cape Town’s administrative area also covers the city’s whole functional area; thus, relationships with neighbouring municipalities are relatively insignificant.

Figure 2: Maps showing city boundaries

| Yellow line – administrative boundary | |

| Red line – urban edge (as far as this could be determined) |

There are a range of local government arrangements internal to the primary city government that can be referred to as two-tier local government, with the relative responsibilities of these tiers depending on how powers and functions are allocated through national legislation. Dar es Salaam, with five municipal councils within the boundary of the city council, has the most complex intra-city relationships; the city council has relatively few functions and revenue sources compared to the internal councils. By contrast, Addis Ababa, has 10 districts (sub-cities) within the city boundary, but the city has primary responsibility for services. A portion of the revenue raised by the city council is paid to the sub-cities in return for administering neighbourhood activities.

Nairobi, Harare, and Cape Town do not have separate urban services institutions within their boundaries, but they do have community liaison arrangements through, for example, ward committees.

All cities must abide by national policies and are, to a large extent, regulated by their national governments. However, the extent to which powers and functions are devolved to local government varies. Cape Town, for example, is the only one of the cities discussed here that is given responsibility for electricity distribution.

It is also important to recognise the difference between de jure devolution and what happens de facto. This was well covered in Africa in Fact Issue 45 on Africa’s urban future, where examples of the marginalisation of local governments in several countries are reported, Harare being an extreme example. All cities are also dependent on transfers from the national fiscus to varying degrees, and national governments can exert control over municipalities through the system of transfers, depending on how well-protected this system is through legislation.

If cities need to relate to provincial governments, this also brings complexity, typically without much benefit. This is the case with Cape Town, where some functions are assigned to the Western Cape Province. This does not apply to the other case study cities.

The management of a city’s functional area is enormously complex, requiring a multitude of functions, many of which are associated with services to households and enterprises. It is not intended to deal with them comprehensively here; rather, the focus is placed on networked infrastructure-intensive functions that are central to the success of cities as integrated urban areas.

The emphasis is on municipal or publicly owned service providers (SOEs), whether they are national or regional. This is not to suggest that private service providers are not a valid service provider option, but this is not considered here, partly as this is not currently a major consideration in the case study cities. The merit of municipal vs SOE service providers is also not considered here other than through the argument that an internal (municipal) service provider does not require a relationship with an external partner.

Although some African countries have national utilities – Uganda, for example – in all five case study countries, water and sanitation services are provided at city level, but with big differences in institutional form.

Cape Town and Harare have municipal supplies, while local SOEs in the other cities provide water and sanitation services. Here, too, there are significant differences, with Dar es Salaam Water Supply and Sanitation Authority (DAWASA) answerable primarily to the national government and serving some areas outside the city boundary. Meanwhile, the Addis Ababa Water and Sewerage Authority is directly answerable to the city and receives funding from it for capital works. The Nairobi Water and Sanitation Company is intermediate between these two, with a substantial degree of autonomy as it is wholly owned by Nairobi County but does not receive funds from the county.

As noted above, the situation in Nairobi is also complicated as there are other county-scale water and sanitation companies active within the Nairobi city functional area: the Kiambu, Oloolaiser and Mavuko water and sewerage companies. The latter two serve the counties of Kajiado and Machakos, and all three include part of the Nairobi functional area in their areas of supply.

Electricity: Four of the five cities discussed here have electricity supplied by national SOEs, with Cape Town the exception, where the city’s own electricity department distributes power to the majority of households and enterprises, with the national electricity provider, Eskom, serving some township areas. In fact, South Africa is quite exceptional internationally for having electricity distribution as a local government function; a few other examples in the world include Los Angeles and some Canadian municipalities. This is surprising, as there are considerable benefits for a city to be an electricity distributor. It is a revenue-rich service and brings a potentially large advantage in that electricity supply can be cut to properties where other payments are in arrears, as happens in Cape Town.

Roads: All the case study cities, and most cities internationally, have multiple agencies managing roads within their functional areas. Typically, a national roads agency will provide and manage the major trunk routes running through the city functional area: Ethiopian Roads Authority (ERA), Tanzania National Roads Agency (TARURA), Kenya Urban Roads Authority (KURA), Zimbabwe National Road Administration (ZINARA) and the South African National Roads Authority (SANRAL).

In some cases—Nairobi and Dar es Salaam, for example—the national agency also manages roads of lower hierarchy within cities. But most typically, these lower-hierarchy roads are provided and managed by the municipality or, in the case of Addis Ababa, by a public entity owned by the city, the Addis Ababa City Roads Authority (AACRA).

The extent of devolution to city road departments is contested in cities such as Nairobi, where the city is marginalised in relation to KURA, and Harare, where the national government limits access to funding for the municipality’s roads.

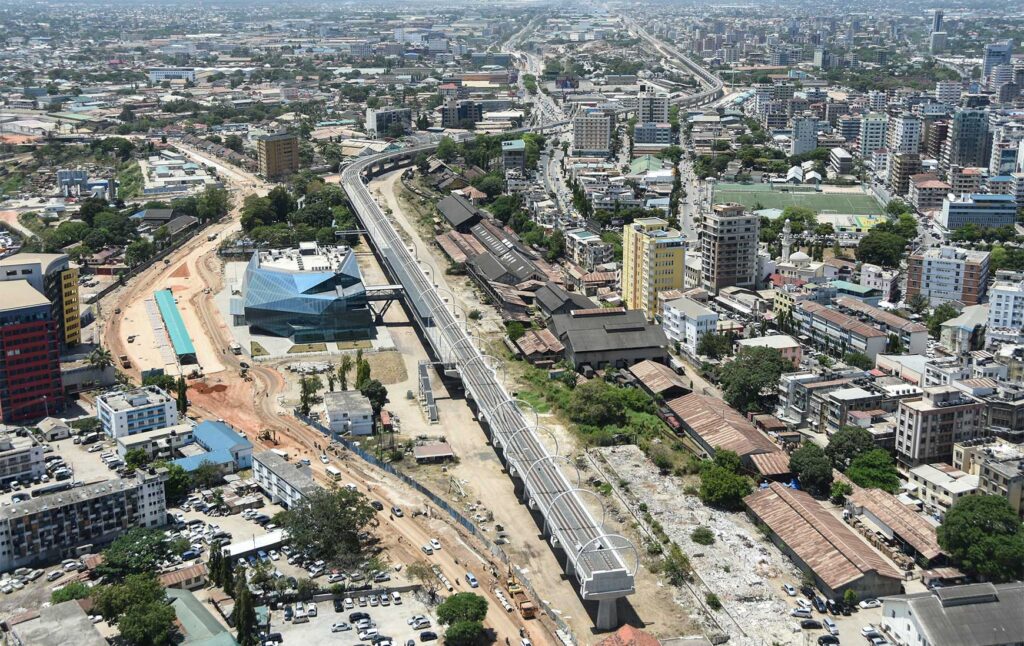

Public transport: In this article, public transport is limited to the provision of mass transit systems, on the assumption that other public transport modes, such as buses and taxis, operate on the roads. Mass transit is of increasing importance for burgeoning African cities where roads are typically congested. This is recognised through recent city-scale interventions: Addis Ababa’s commuter rail system, Dar es Salaam’s bus rapid transit (BRT) system, and the BRT system currently under construction in Nairobi.

While these mass transit systems are promoted as successes in improving city viability, the Cape Town commuter rail system is failing and in decline due to corruption and mismanagement. In Addis Ababa and Cape Town, the rail system is run by national SOEs: the Ethiopian Railways Corporation (ERC) and the Passenger Rail Agency of South Africa (PRASA). Dar es Salaam has a two-tier BRT arrangement, with Dar es Salaam Urban Transport Authority (DUTA) as the asset owner and Dar es Salaam Rapid Transit (DART) as the operator. Nairobi also has a split system, with the planning by the Nairobi Metropolitan Area Transport Authority, which covers the city’s functional area (including Nairobi’s neighbouring counties), intending to employ private operators to run the buses on the BRT corridors.

The benefit of having fewer external parties engaged in city management as functional areas is obviously not the only factor influencing their viability. However, it is argued here that this is most important, with Cape Town an example of institutional simplicity, where the city council has responsibility for the whole functional area and where the city directly provides all networked services other than public transport.

It has only three primary relationships to manage: national government, PRASA (for public transport), and Eskom for electricity distribution in part of the city. It is recognised that Cape Town also has other advantages in relation to other case study cities: a strong economy, a substantial revenue base, and political stability.

Addis Ababa also has a relatively uncomplicated set of relationships to manage, six in number: National government, Oromia regional government, the national electricity provider, the national rail corporation, and two municipally owned entities responsible for water sanitation and roads.

In Harare’s case, the city has seven external organisations to manage in addition to national government, with complexity created by the spillover of the functional area into five neighbouring local authorities. On the other hand, it has only two external service providers to consider, those responsible for electricity and roads.

Nairobi has the disadvantage that the city must deal with three other counties serving the functional area of the city, four water and sanitation providers, a national electricity provider, a national roads authority and a public transport authority, and national government: 11 organisations in total.

In the case of Dar es Salaam, the city council must relate to five municipal councils, three local SOEs responsible for water, sanitation, and public transport, two national SEOs providing roads and electricity, plus national government: 12 organisations in total.

In the final analysis, there are manifold benefits to having a strong single-tier municipality serving the whole functional area of a city. Fragmentation creates administrative and political complexity and reduces the ability of local government to raise revenue and finance capital works.

Ian Palmer

Ian Palmer is the founder of PDG, a leading development consultancy in South Africa. He has 45 years' experience in infrastructure and urban development. He remains with PDG part-time as an associate. For the past 10 years, he has undertaken academic work as an adjunct professor at the University of Cape Town, attached to the African Centre for Cities. Over the period 1996–2012, Ian was a trustee and deputy chairperson of Mvula Trust, a leading NGO in water supply and sanitation. He has been the team leader on over a hundred research and consulting projects in South Africa. Also, he has experience working in Zambia, Mozambique, Uganda, Rwanda, Ethiopia, and Kenya for various development agencies.