*Youssouf’s life took a turn for the worse after the last two goats he was left with died suddenly from a combination of thirst, hunger and disease as a result of the harsh climatic conditions of southern Niger. This vast area includes Dosso, Maradi and Zinder, as well as parts of the Diffa and Tillabéri regions.

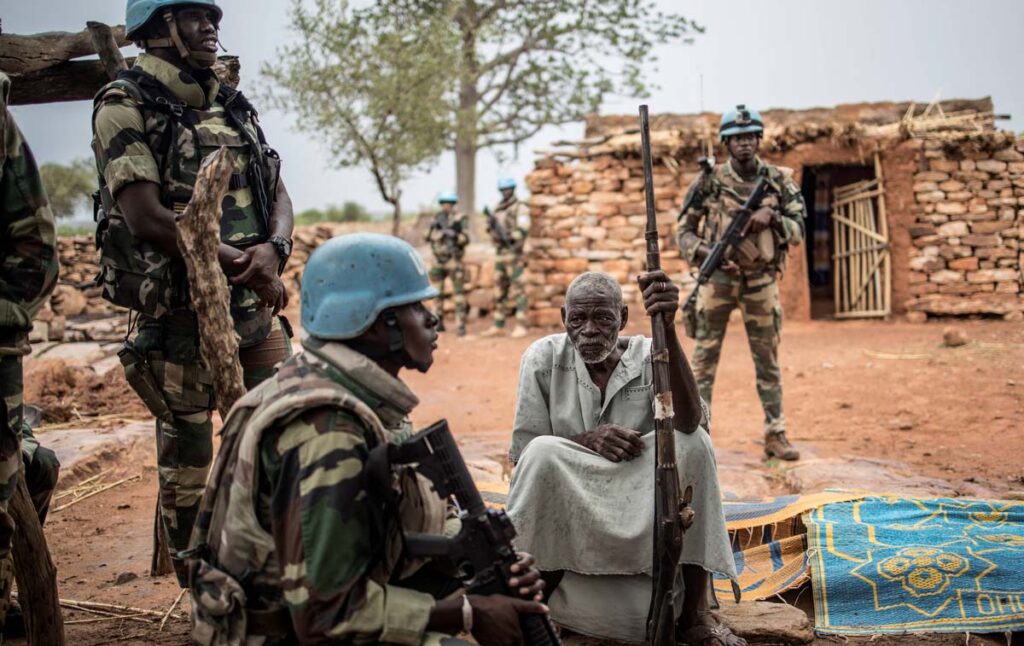

Livestock farmers in the central Sahel, a region that includes Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger, face challenges, including a scarcity of grazing, climate change, disease outbreaks, lack of government support, and cattle rustling.

The region also suffers regular attacks by the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) and al-Qaeda-affiliated Jama’at Nasr al-Islam wal Muslimin (JNIM).

While some of his peers – mostly farmworkers – joined armed groups to “turn their lives around”, an uneducated and unskilled Youssouf headed south, to Benin, to try rebuilding his life shattered by the untimely death of his livestock.

“I don’t want to kill innocent people who happen to be my own people,” he told Africa in Fact from the economic capital Cotonou, where he currently works as a home security guard and earns 40,000 CFA Francs (nearly $70) per month.

“We have no education, no skills and no jobs, so the temptation is huge to embrace insurgency because there is no hope for the future. We thought the July 2023 military coup would improve our living conditions, boost support for herders and farmers, eradicate terrorism, fight government corruption, and rebuild democracy, but we were wrong. The new authorities are doing the same thing as their predecessors, so it is a helpless situation,” he said.

According to a Tony Blair Institute for Global Change November 2024 report, violent extremists in the central Sahel are ever more able to exploit marginalised communities and those disillusioned with their governments. “Resource-scarce communities, struggling with the negative impacts of climate change as they attempt to cultivate arable land and maintain access to water and grazing resources, are particularly vulnerable to the actions of violent-extremist groups, which can be described as the single largest threat to peace, security and development in the central Sahel,” it said.

Year in and year out, the situation remains the same: Previous Sahelian governments’ efforts to address climate change have failed, prompting some experts to call for innovative approaches to prevent affected Sahelian youths from joining armed groups.

Sophie Desmidt, Associate Director for peaceful societies and accountable governance, and head of peace, security and resilience at the European Centre for Policy Development Management (ECDPM), told Africa in Fact that to talk about innovation, one would need to think about actually tackling this as a priority in the first place.

“The central Sahel countries are amongst the most fragile settings but are the least funded in terms of climate adaptation,” she said. “These countries have now cut off ties with most partners that were most supportive of these issues, but even with that support, communities were not really able to turn around the climate-security challenges.

“To tackle climate security effectively, the entry points are very apparent: natural resource management, agriculture and climate- and peace-sensitive investments focusing on youth employment. There are some innovative examples from Somalia, where diaspora crowdfunded investments have integrated climate and peacebuilding, and climate resilience – these could be explored in the Sahel too, though the diaspora link in Horn of Africa/Somalia is quite distinct and particular, so innovative examples cannot be transposed easily.”

Far from his home in southern Niger, Youssouf can only dream that the government will listen to Desmidt and apply her innovative recommendations to effectively fight climate change.

Like Youssouf, other disgruntled Sahelian and West African youths fleeing conflict and poverty have sought their fortunes in Benin. Instead of joining JNIM, which is headquartered in the central Mali regions of Mopti and Bandiagara, Ousmane* has set his sights on reaching Europe with the help of a human trafficking syndicate operating in Cotonou and that has partners all over West and North Africa.

He said he had already made contact with “some people” and everything was fine. “We are still negotiating the terms. It’s a risky adventure but it’s better trying than staying in Mopti, where terrorists are killing people every day under the nose of these generals who are powerless to stop them and doing nothing for the people since they came in power.

“These people said I shouldn’t worry because they have partners all over West and North Africa, and everything will be done smoothly until I reach Europe,” Ousmane said.

Back home, Ousmane used to help his father breed cows, sheep and goats, but the family suffered a setback after gunmen, believed to be terrorists, raided their village, killed people, set houses on fire and stole cattle.

For years, Benin’s proximity to Nigeria has made it the epicentre of transnational crime in West Africa, where cyber criminals, human smugglers, drug traffickers, counterfeit currency makers and prostitution kingpins, among others, set up “offices” to coordinate their activities that span from the region to places that include central and North Africa, Europe and the United States.

Sahel-based terrorist groups have also been able to cross over with ease to launch deadly attacks in northern Benin and Togo.

A source close to the Benin government told Africa in Fact that the country was doing its best to carry out operations to dismantle transnational criminal networks and boosting border control and security, but it needed its neighbours to do their part.

“The most successful approach to eradicate transnational crime and stop armed groups from crisscrossing border towns and villages is through a regional coordinated integrated approach,” our informant said. “The unresponsiveness of our neighbours is greatly upsetting, considering these groups originate there.”

Instead of seeking to collaborate with its African counterparts, central Sahel countries have looked east, from where they have sought military assistance from countries such as Russia and Iran to fight terrorism – a decision that has so far proved futile as attacks have shown no sign of abating.

Asked to comment on Russian and Iranian influence on junta-led Sahel countries, Desmidt said, “I am not sure what can be done here in terms of innovation or for whom – it’s just that geopolitics are defining what partnerships are looking like. Russia has been a partner for these countries for longer, though the security component is now scaled up, even if it’s far from delivering what they promised.

“As long as these junta-led countries see merit in nurturing the relationship with Iran and Russia [even if only for their own narrow benefits] while they also further expand their relationships with Turkey and the Gulf, I don’t see much changing or ‘innovation’.

“What I do see is that the European Union is still far from providing a counter-offer of some sort – the reality will be much more of a shared space of partnership in the central Sahel, something which might sit uncomfortably with one [partner] or another. But, the EU could build partnerships with some of the new partners, particularly Turkey, to see what could be achieved jointly.”

The Beninese source said, “If you ask my honest opinion about an innovative approach to eradicating violence in central Sahel, I will tell you that it is dialogue.” The official deplored the arrogance and political immaturity of the Sahel juntas. “It is high time that these juntas understood that armed conflict can no longer be solely eradicated through the acquisition of high-tech military equipment,” he said. “Russian choppers or jets, or Turkish drones or recruiting foreign mercenaries will not solve the terrorism issue, but dialogue can. Sitting down to talk between Malians, Burkinabe, and Nigeriens has become imperative under the current situation.”

According to the Beninese official, a package of successful solutions consists of looking at the core issues that have triggered terrorism in the region. It must include aspects such as an inclusive national dialogue, socio-economic development programmes, the introduction of new ways of effectively combating climate change, improving service delivery and governance, strengthening civil society, and addressing ethnic conflicts, which mostly resulted from the control of natural resources and marginalisation.

The conflict in the Sahel region has also led to a rise in disinformation campaigns, which in turn have fuelled instability, generated anti-western sentiments amid the deterioration of relations with western countries and Russia’s rising influence, impacted public trust and political discourse, and undermined counterterrorism efforts.

False narratives trending in Sahel streets, often fabricated by non-African groups and pro-government supporters, include “some African countries are harbouring terrorist bases”, “western countries are funding and equipping terrorist groups”, “all the Fulani people are jihadists” and “Fulani communities support jihadist groups” among others.

Desmidt believes Europe is missing an opportunity. “As far as Europe/the EU goes, it has not invested in strategic communication, emphasising spending rather than impact and results. This is a shame, because if you dig deeper, the impact is there, and some EU member states such as Belgium have been present for decades working with communities and authorities in pivotal sectors.”

She added that the EU, and possibly the EU member states still active and operating in the region, must cooperate in investing in strategic communication to effectively counter these disinformation campaigns.

“If the EU wants to invest in fragile settings, including in the central Sahel through the Global Gateway strategic corridors, this will need to be matched with communication and presence on the ground,” She said.

* Names changed to protect the sources’ identity.

Kinshasa-born Issa Sikiti da Silva is an award-winning freelance journalist. Winner of the SADC Media 2010 Awards in the print category, he has travelled extensively across the African continent. He lived in South Africa for 18 years, where he worked for 10 years as a journalist before leaving for West Africa, and later to East Africa, to work as a foreign correspondent. He is currently based in Dakar, Senegal.