Land disputes between immigrants and Ivorians incited last year’s devastating post- electoral conflict. As those who fled the violence return, tensions over land ownership are rising.

by Monica Mark

In his novel “Robert and the Catapilas”, Ivorian writer Venance Konan describes the land disputes that have plagued Côte d’Ivoire for generations. Catapilas refers to the hard-working migrant farmworkers from neighbouring Burkina Faso who are named after the heavy-lifting Caterpillar construction machinery. One Catapilaconvinces Robert, the village layabout, to exchange his ancestral land for money, cattle and wine.

But trouble is brewing. While the Catapila sets about tilling his newly-acquired land, Robert flushes his money on booze and merry-making. By the time his alcoholic stupor lifts, he is broke and without the land which produced enough to feed him. Worse, he is tormented by the constant drone of the Catapila’s tractor ploughing his former land. Eventually Robert convinces the villagers that the Catapila must pay him a monthly sum to “appease the ancestors”—and provide Robert with easy cash.

“The story is pretty much exactly what happened in a village I know, but it’s a story that resonates with millions of Ivorians,” said Mr Konan, the writer. “The problem was that there was no concept of land rights. People just knew this land had belonged to this family for aeons.”

Land disputes have plagued Côte d’Ivoire for more than fifty years. They resurfaced during the 2011 post-electoral conflict in which 3,000 died and 1m of the West African country’s 20m inhabitants were displaced internally. At their heart, decades of foreign migration fuelled nationalism and exclusion, as described in “Robert and the Catapilas”.

The seeds of conflict were sown in the heady days following independence in 1960. Keen to exploit the fertile soil, the country’s first president, Félix Houphouët- Boigny, invited cheaper labour from poorer Sahelian countries, neighbouring Mali and Burkina Faso in particular, to come and work the country’s fields. Under this burgeoning labour force, Côte d’Ivoire became the world’s biggest cocoa grower. Many immigrants settled in the country’s west, where palm oil, rubber, coffee and cocoa plantations abound.

Côte d’Ivoire became renowned as the “West African miracle” reflecting this policy’s success. But these laudatory labels betrayed the growing resentment against immigrant communities as world cocoa prices fell and the Ivorian phenomenon faded. When Mr Houphouët-Boigny died in 1993, crisis followed: his successors capitalised on voter anxiety and blamed the immigrants for the downward-spiralling economy.

This anti-immigrant nationalism, called Ivorité, led to a law that defined “true” Ivorians as persons who could prove that they and their two parents were Ivorian-born. Only these Ivorians would be considered citizens with voting rights.

Many southerners still question the Ivorian identity of their northern compatriots, who are historically and culturally closer to the country’s Sahelian neighbours. In practice, this meant that not only immigrants and their immediate descendants, but also many Ivorians who were easily identifiable as northerners, were simply excluded from political rights.

This marginalisation fuelled the conflict surrounding the country’s controversial land ownership rights, which are governed by the same principles of Ivorian citizenship. Only “true Ivorians” can own land, despite many land purchases by migrant workers, as described in “Robert and the Catapilas”.

Côte d’Ivoire’s immigrant population is Africa’s highest, and one of the highest in the world. In 2010, 2.4m or 11.2% of its 20m population, were immigrants. South Africa and Ghana had the second- and third-highest immigrant populations in Africa.

Each has about 1.9m immigrants, making up 3.7% of the South African and 7.6% of the Ghanaian populations, according to the International Organisation for Migration.

Identity politics resurfaced during the elections held in October and November 2010. During the campaign, posters advertised president Laurent Gbagbo as the “100% Ivorian” candidate. The results were so close that incumbent Mr Gbagbo refused to stand aside and the winner, Alassane Ouattara, was sworn in as president only in May 2011, after five months of violence. Mr Gbagbo’s supporters were mainly southern ethnic groups while northerners voted mostly for Mr Ouattara.

The worst violence during the 2011 post-election crisis took place outside the economic capital, Abidjan, in the south-east. The country’s west, rich in minerals such as diamonds, iron and nickel, was also wracked by deadly clashes.

Pro-Gbagbo militias, mainly from the Guéré and other southern tribes, regularly clashed with settlers, mostly from Burkina Faso and Mali, but also with Ivorians from other parts of the country. But during the conflict, power switched hands in favour of rebels who supported Mr Ouattara. The native Guéré found themselves displaced from their own lands. On April 2nd 2011 at the height of the conflict, human-rights groups discovered three mass graves in the western town of Duékoué that contained the bodies of several hundred civilians—predominantly from the Guéré tribe.

“What we have in the west today is a situation which started off politically- driven. Now, though, it’s motivated by a desire for revenge, a cycle that is very difficult to break,” a presidential aide explained.

In Bakoubly, a cocoa-growing town in the south-west, a small group of Guéré recently returned to find their land occupied by northerners. “For years we suffered even though many of us were born here. Now [the returnees] know what it is like,” a local Burkinabe community leader said.

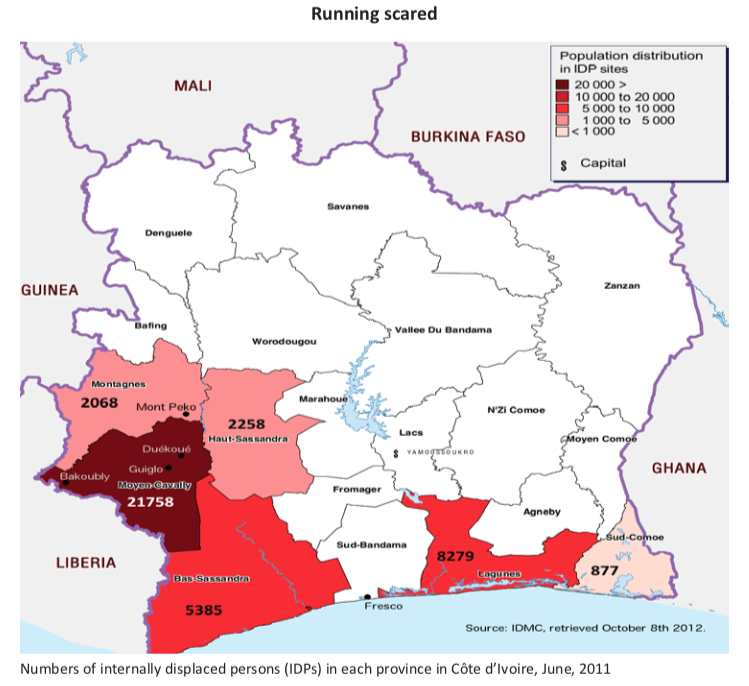

The post-election violence left almost 1m Ivorians displaced within the country

in March 2011, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees reported. Many have since returned. The number of internally displaced persons (IDPs) had shrunk to 247,000 by September last year.

Returning home, many IDPs discovered that their land had been sold or leased in their absence, often to immigrants, according to the Norwegian Refugee Council’s Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC). The absence of formal land ownership rights eases these informal exchanges, which have resulted in violent land clashes.

In May last year, at least ten people were killed in the west near Mont Peko, where illegal land sales are common. In September last year, more than 20 people were seriously injured in a confrontation in the southern town of Fresco, according to Human Rights Watch.

As more IDPs return home, disputes over land are likely to increase. In the west, close to 900 internally displaced ethnic Burkinabe decided to remain in a camp outside Guiglo instead of returning to their land, fearing retribution from the indigenous population there.

Violent attacks are often justified by the behaviour of the country’s leaders. Mr Ouattara has yet to investigate alleged human rights abuses by the forces loyal to him, while several high-profile Gbabgo supporters have been charged and sentenced. Mr Gbagbo himself awaits trial at the International Criminal Court.

“This situation is a ticking time bomb,” said Jacques Varlet, a private land consultant. A national reconciliation commission is largely ineffectual. The government is nevertheless aware that land reforms are urgently needed. A three-day seminar in June produced no formal announcements.

Applied clearly and fairly, some officials argued, the current legislation is enough to regulate land disputes. The 1998 rural land law stipulates converting customary land ownership to formal legal title.

But the process of formalising land rights has been painfully slow. In 2009, authorities had not issued any landholding deeds and only 23 surveyors were expected to demarcate plots across 20m hectares, the IDMC reported. Last year, the ministry of agriculture, with advice from the European Union, handed out some 2,000 landholding deeds through customary courts, said the agriculture minister, Mamadou Sangafowa. “We prefer to go slowly. In France, it took 85 years for land ownership rights to be solved, so time is not the issue.”

Even more problematic than its slow implementation, the law bars immigrants and their children from owning land and permits them only long-term leases. “We have a very clear approach to the situation. Land in Côte d’Ivoire cannot be sold [to foreigners], it can only be leased,” Mr Sangafowa said.

Others have argued that land should be a commercialised, tradeable com- modity, without ownership restrictions. This would reduce clashes while stemming the underlying economic undertones of land disputes, said politician Mamadou Coulibaly.

“If the state was happy for landowners to pay 10 francs [less than $0.02] per square metre [in taxes], that would benefit the state budget to the tune of 2 trillion annually [$3.7 billion] … Such sums are more than enough to finance infrastructure in rural zones and pay back debt without being overly indebted to international donors. This strategy is not only realistic, but it creates jobs, putting an end to land disputes and encouraging agricultural investment,” Mr Coulibaly said.

A major obstacle to reforming land policy is that the current political forum excludes any meaningful opposition. Mr Ouattara’s heavy-handed approach has undermined attempts to reach out to hard-core Gbagbo supporters.

Since a coup in neighbouring Mali last March, regional migration has increased. The pressure is on to find a solution that not only clarifies land rights but also leads to long-term stability.