South Africa’s housing market

In one of Africa’s largest economies, the middle class cannot buy a home because they cannot get loans

Neliswa Khumalo, 46 years old, shares a peach-coloured four-roomed government-subsidised house with her three children in Soweto, an urban sprawl west of Johannesburg. She qualified for this house in 2002 because her salary as a shop assistant was under $350 a month. MsKhumalo’s fortunes have changed and she now works as an office administrator earning around $1,200 a month. Ms Khumalo would like to sell her RDP house—named after the 1994 Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP)—and move on. A common predicament prevents her: she cannot find an affordable home.

The logic of capitalist property markets asserts that homeowners should be able to climb the property ladder by leveraging, improving and selling their homes, and moving on to greener pastures. But the poor are often unable to get onto the first rung and sometimes even slide back into informal housing after receiving a government-subsidised house. The housing market is also failing people such as Ms Khumalo, who form part of South Africa’s black middle class.

Defining the middle class is a fraught exercise, particularly in developing countries. Two economists, Justin Visagie and Dorrit Posel writing in 2013 in the journal Development Southern Africa, looked at various local and international studies that adoptedrelative and absolute approaches to gauge the middle class.

The relative measures capturethe middle strata of income distribution, often centred on median income. Mr Visagie and MsPosel show that South Africans in this range earn very poorly, between $45 to $170 per month; their lifestyles resemble that of the working poor, not the middle class.

Absolute measures use indicators such as occupation, affluence and lifestyle (using proxies such as the standard of housing or luxury consumption) to define a middle class. Local studies reviewed by Mr Visagie and Ms Posel that use this method place the bottom threshold for the “middle class” at a monthly income of anywhere between $180 and $700, with the upper threshold often not specified.

South Africa’s government, housing experts and the financial sector have identified a “gap market” or “affordable housing market” made up of those earning between $350 and $1,800 a month. They earn too much to qualify for RDP houses but struggle to find affordable homes in the private market. These individuals account for 18% of South Africa’s 52m population, according to Statistics South Africa.

A shortage of privately-built stock and constraints on government stock entering the secondary housing market explain the lack of affordable housing for this gap market. Credit plays a huge role.

After the transition to democracy 20 years ago, the newly-elected government centred housing policy on private homeownership through government-fundedRDP houses, privately-built stock and privatised apartheid-era state-owned accommodation. Access to credit was essential for developers and individuals: it would supposedly allow RDP homeowners, such as Ms Khumalo, to gradually improve their “starter houses” and it would provide loans to those ineligible for the government subsidy to purchase a home.

Despite a multitude of agreements between government and the banking sector, credit provision to these groups has been and remains feeble. Ms Khumalo has not succeeded in getting a bank loan and does not understand the denial of her application. This difficulty in accessing credit is typical: of the 2.94m government subsidised houses delivered between 1994 and 2009, only 120,000 were accompanied by mortgages to expand or improve the house, according to a 2011 study by Shisaka Development Management Services, a consultancy based in Johannesburg.

A similar problem confronts Moses and Nonkosi Dlamini, a couple living in Johannesburg’s Alexandra township, who work in a small electronics shop as a sales manager and a store assistant respectively. Despite having a household monthly income of $900, they have not succeeded in securing a mortgage to buy a house.

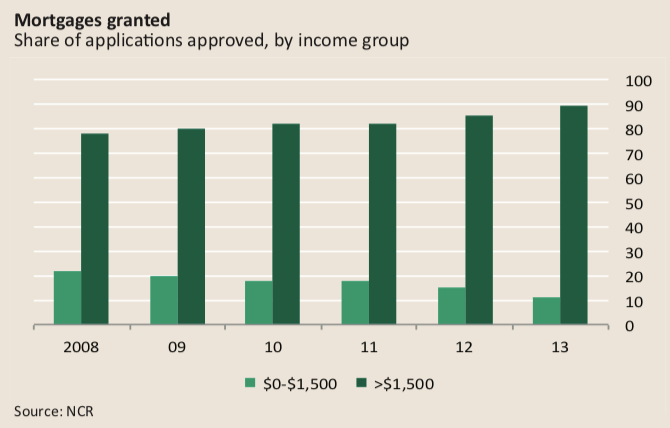

The 2004 Financial Services Charter sought to expand lending to those earning $350-$750 a month. After the first phase of the charter expired in 2009, the banks revised the “affordable market” to those earning $350-$1,500 a month, adjusted each year by inflation so that it now reaches up to $1,800 a month. Despite this revision, mortgage lending to this market ($350-$750 for 2004-2008 and $350-$1,500 for 2009-2011) has decreased. The great majority of mortgages, 80% to 90%, are granted to those earning above $1,500.

Non-mortgage lending is often a more suitable and accessible alternative to mortgages. Ms Khumalo’s neighbours, for example, used a microfinance loan to add on an extra room that they rent out to earn extra income. Neither official nor independent composite statistics on microloans are available. But estimates derived from the government’s National Credit Regulator (NCR) reveal a trebling of the value of outstanding microloans between 2000 and 2013. Despite this increase, in 2013 the highest estimate of outstanding housing microfinance is $1.1 billion compared with outstanding mortgages to those earning above $1,500 valued at approximately $70 billion.

Low levels of housing credit have persisted while overall credit in the economy has risen. Mortgages account for the largest share of household credit, averaging about 60% of total outstanding credit for the past seven years, according to the NCR. Unsecured and retail lending, however, have seen the most vigorous expansion of credit in recent years. For example, unsecured loans not backed by a house, car or other assets have risen from 4% of outstanding debt in 2007 to 11% in 2014.

This credit expansion played a crucial role in fuelling the consumption-led economic boom of the mid-2000s. It also led to a sharp rise in default rates. This has affected middle-class housing in two important ways.

First, over-indebtedness makes people ineligible to qualify for housing loans or unable to repay them. For a long time the Dlaminis, like millions of other poor South Africans, were borrowing just to pay the bills and put food on the table. In asurvey published in 2012 by the NCR and FinMark Trust, an NGO that promotes financial inclusion, over half the respondents cited these two reasons for their borrowing.

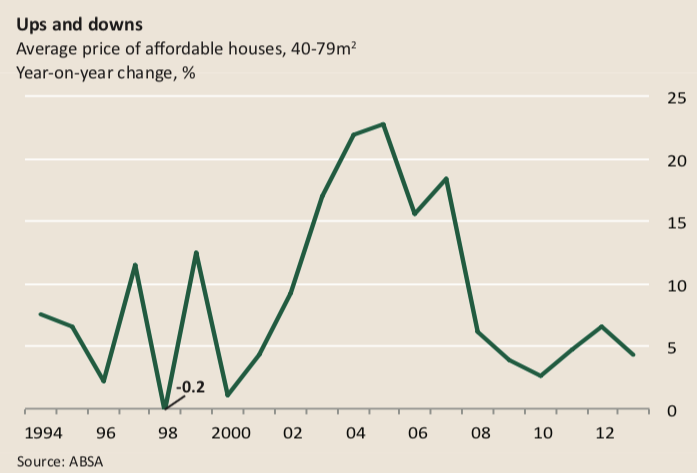

Second, capital inflows—as well as land and property speculation—contributed towards steady property market appreciation, albeit from a low base. The Economist in 2009 ranked South Africa’s real estate bubble the world’s most inflationary between 1997 and 2008.

This has made potential homes for Ms Khumalo more expensive. The average price for affordable or small houses was $34,200 in the fourth quarter of 2013, according the Absa Housing Review. But only those earning about $1,350 per month or above (based on standard mortgage terms and repayments of 25% of household income) could afford a house of that value. The FinMark Trust 2013 “Housing Finance Yearbook” quotes the cheapest newly-built house in this market, in desperately short supply, as costing $24,500, just above the means of the Dlaminis. Meanwhile the value of Ms Khumalo’s RDP house has not appreciated in line with the national trend. Between 2004 and 2009, the Shisaka study estimates that the construction cost of RDP houses ranged from $13,100 to $15,700, while the average resale price was only $7,100. The state restricts resale of RDP homes to five years after ownership is granted, a limitation that contributes to depressing their sales value.

In the ostensible progression up the housing ladder, access to credit and property market appreciation are meant to play a critical role. However, credit has been heavily curtailed in South Africa and rising house prices have benefited existing wealthier property owners. For the millions like Ms Khumalo and the Dlaminis, who dream of climbing the middle-class property ladder, housing is simply out of reach.

[author] [author_image timthumb=’on’][/author_image] [author_info]Gilad Isaacs is an independent economist and political commentator. He holds an MA in political economy from New York University and an MSc from the School of Oriental and African Studies, where he is completing a PhD in economics. [/author_info] [/author]