Côte d’Ivoire: citizenship and property rights

Land laws in this west African nation have often been used to stimulate economic growth and secure political advantage

On a recent humid July afternoon Affoussy Bamba discussed Côte d’Ivoire’s amazing turnaround. A former spokeswoman for the rebel side during two civil wars, she sat on her terrace in Abidjan, the commercial capital. Sipping mango juice, she reflected on this country’s transformation from a poster child for successful African development into a two-time warzone.

Two phrases resonated during that hour-long conversation: “Citizenship and land,” she said. “Mess with those two things, and you’ll have a rebellion.”

Her powerfully simple adage is tragically correct. Ms Bamba is now the country’s communications minister, a post commensurate with her sharp intellect and wit. But her position would have been unimaginable had she not been on the winning side of the latest Ivorian civil war, which ended in April 2011 after four months of conflict.

Most ink spilled on the Ivorian civil wars documents how ethno-political exclusion caused the so-called “Ivorian miracle” to derail into violent conflict. Less well known, however, is the backstory behind Côte d’Ivoire’s descent from prosperity to political violence: over three decades the policies that laid the foundation for the country’s stratospheric economic growth rates sowed the seeds of conflict that germinated into the first 2002-2007 civil war. In short, changes to property rights are amongthe most important root causes of the country’s two civil wars.

Shortly after independence from France in 1960, President Félix Houphouët-Boigny envisioned transforming Côte d’Ivoire into the world’s cocoa capital. He quickly realised, however, that the country lacked enough hands to cultivate the rich soils in the country’s west and southwest cocoa plantations. To counteract this labour shortage, he liberalised property rights, hoping to flood the fields with migrant workers—and to steep world markets in Ivorian cocoa.

The laws, known as mise en valeur(“put to use”) land tenure, meant that the land belonged to whoever was willing to put it to good, productive use. “Land belongs to the person who brings it into production, providing that usage rights have been formally registered,” Mr Houphouët-Boigny said in a March 1967decree.

It quickly became clear how easy it would be to own land legally under Mr Houphouët-Boigny. Word spread across the region, particularly to Burkina Faso and Mali: move to Côte d’Ivoire’s cocoa fields and you could become a landowner with healthy profits from cocoa exports, explained Ryan Bubb, a New York University law professor, in a 2009 working paper for the World Bank.

“The registration proviso of the decree was unobserved,” he added, because Mr Houphouët-Boigny was eager to flood the country with labour as quickly as possible, without the bureaucratic paperwork.

At first, it was just about economic expediency—more people to work the land, no matter where they came from, without the red tape. Then it became a tactic to secure electoral advantage, explains Yale University’s Mike McGovern. “They [migrants] were not only encouraged to come and farm cocoa in the forests of the west, they were also given voting and other de factocitizenship rights by the PDCI [the Democratic Party of Côte d’Ivoire] which knew it could count on their vote,” he writes in his 2011 book, “Making War in Côte d’Ivoire”.

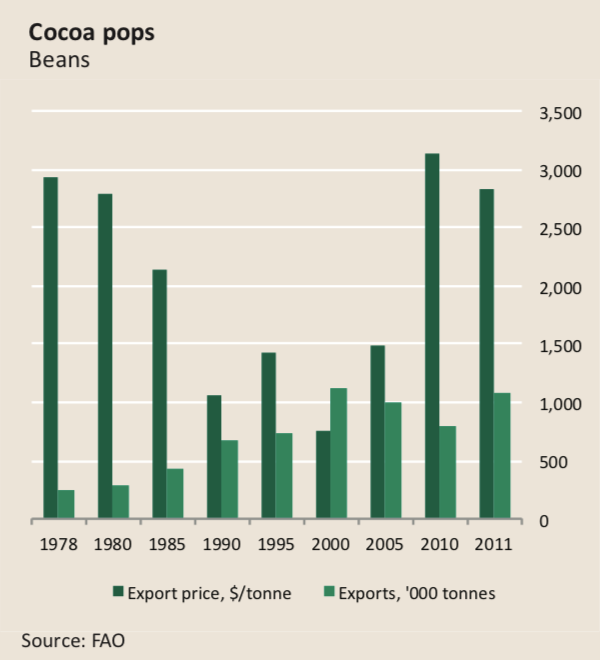

This two-fisted masterstroke by Mr Houphouët-Boigny’s dominant PDCI regime was not universally popular, however—particularly with the bursting of the cocoa bubble that had fuelled Ivorian growth. In 1978, the year that Côte d’Ivoire eclipsed Ghana as the world’s leading cocoa producer, a metric tonne of cocoa could fetch roughly $3,000 on global markets. By the early 1990s the same amount was worth about a third of the price, according to a 2007 IMF report.

With cocoa prices sagging and the rich lands becoming densely inhabited, the Ivorian population—and their descendants who had worked the land since colonial times—turned sullen. Suddenly, from feeling prosperous, everyone was feeling poor. The long-time locals blamed the so-called foreign “strangers”, even if those outsiders had been working the land for decades.

These differences in the west—between Ivorians who had worked the land for generations and those that arrived more recently, often coming from the north—mirrored a national rift that was forming more generally between north and south. The south was home to the bustling commercial capital, Abidjan, and the southwest was the hub of cocoa production. The north, however, was home to far less economic activity. Many northerners (including migrants from Côte d’Ivoire’s northern neighbours, Mali and Burkina Faso) had responded to Mr Houphouët-Boigny’s earlier call to farm the cocoa fields. They moved south in droves from other countries, and from northern Côte d’Ivoire.

These dynamics—between north and south generally, and between “northern strangers” and “indigenous southerners” farming the cocoa fields in the west—became combustible with a cultural, linguistic, and religious divide of Muslims dominating in the north and Christians in the south, a recipe that stoked resentment and scapegoating while the economy withered.

This chorus of discontent was not loud enough to compel a major political shift or a change in de jureproperty rights law or de factoland allocation. After all, just as Mr Houphouët-Boigny made Côte d’Ivoire the poster child for African development success, he was the archetypical master of political patronage. He seemed to have an endless supply of hands that kept the lids on the simmering pots of restlessness across a country cursed with a deteriorating economy.

Everything changed, however, with Mr Houphouët-Boigny’s death in December 1993. Henri Konan Bedié, then president of the National Assembly, assumed the duties of the late president in accordance with the constitution. Alassane Ouattara, the prime minister, initially refused to recognise Mr Bedié’s right of succession, but resigned two days later.

The new president soon realised that the rifts in the western cocoa regions reflected a national division between the country’s northern and southern halves. Mr Bedié, from the south, feared that a northerner, such as Mr Ouattara, could exploit this national divide and threaten his chances of winning the 1995 election, the country’s first genuinely multi-party contest since independence.

He set about neutralising northern political power through a new electoral code, which excluded Mr Ouattara from the 1995 election. Mr Bedié charged that Mr Ouattara was a foreigner born to foreign parents—a “stranger” to Côte d’Ivoire, just as migrants cultivating cocoa were “strangers” to those in the west who believed they had longer-standing ownership of the land.

A political strategy to marginalise Mr Ouattara and weaken the clout of northerners in national politics drove a campaign of exclusion towards the north’s general population that continued throughout the decade.

Ms Bamba, back on her terrace, recalls this period. She recounts how friends had their identification cards torn up by police officers without justification, effectively shredding their claims to Ivorian citizenship and their rights to vote. “I felt targeted and excluded,” she explained. “We all did.”

The 1998 Rural Land Law expanded this strategy of marginalising those with “questionable” citizenship by stipulating that only Ivorian citizens could own rural land—the only land that mattered in an economy based almost exclusively on cocoa. The law was based on the concept of Ivoirité, whether someone was truly Ivorian or not—a murky concept at best, particularly in a land where lineage in reference to colonial borders did not always mirror the current map.

This was a complete inversion of Mr Houphouët-Boigny’s property rights programme. This time the manipulation of land laws was used not to maximise cocoa production but to maximise social strife and sideline political rivals.

A year later a coup d’état rocked Côte d’Ivoire, a previously unthinkable event in Abidjan, the prosperous “Paris of west Africa”. The next year, the coup president, General Robert Guéï, continued the exclusionary politics of Ivoirité. Again, Mr Ouattara was not allowed to stand in the 2000 elections. Like Mr Bedié before him, General Guéï realised that sidelining the candidate representing the northern half of the country was the surest way to guarantee electoral victory.

Two years later, on September 19th 2002, the first civil war began; it would rage on and off for five years. In 2010-11, another civil war would resume the cycle of conflict—this time in the aftermath of an election where Mr Ouattara, largely as a result of international pressure after the first Ivorian civil war, was finally allowed to stand for president and won.

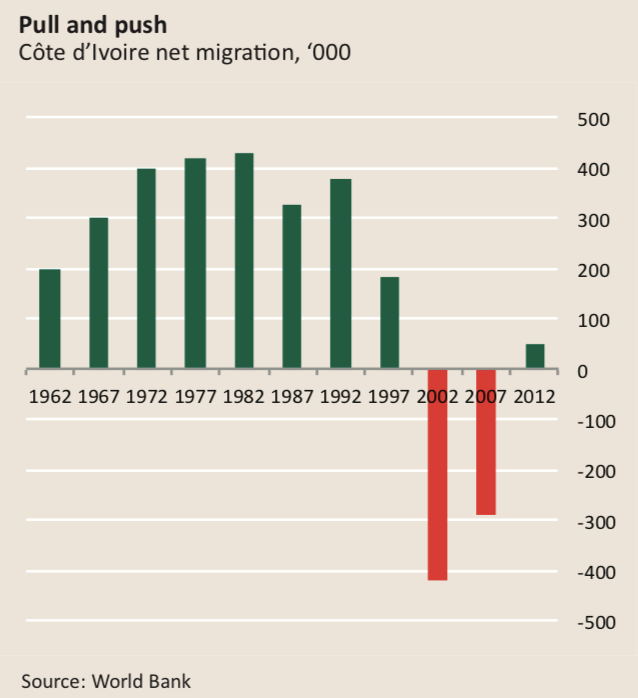

Despite these conflicts, directly tied to property rights, the issue of land tenure has festered. The wars forced 220,000 people to flee from western Côte d’Ivoire into Liberia, according to the UN refugee agency. During the second war, thousands of Ouattara supporters—usually people from the north, or migrants from Burkina Faso—fled from militias supporting his vanquished rival, Laurent Gbagbo, the former president. They left behind land—opening it to new cultivators who claimed the right to own the land indefinitely. When displaced refugees came back to the land they previously owned, they were kept off it, sometimes forcibly, by the new occupants.

This fuelled other property rights abuses. A 2013 Human Rights Watch report describes how some migrants—occasionally claiming they were displaced refugees, even if they were not—seized land in the post-conflict vacuum of power, before the newly-established Ouattara government had reasserted control. They claimed these takeovers were their “reward” for fighting for the pro-Ouattara militias during the conflict.

Clearly, this is illegal, but it is borne out of the “whoever farms it, owns it” mentality established during the Houphouët-Boigny era. That historical legacy is creating problems today. Those who lost their land during the conflict now fear that a re-establishment of de jureproperty rights that recognise legal titles rather than de factocultivation may leave them with nothing.

In August 2013 the government issued modest reforms to the law on rural land tenure, aimed at bringing more land into the formal economy. It streamlined the transferring of property and reduced the property transfer tax.

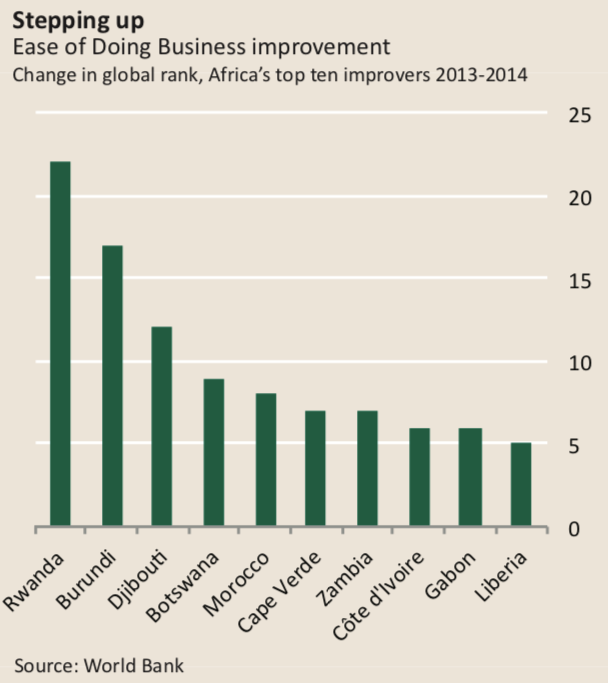

This contributed to an overall improvement in property rights law in the country, a condition that makes it easier to do business, according to the World Bank. As a result, Côte d’Ivoire, though still at a low rank of 167 out of 189 countries, is among the world’s top ten economies making the biggest improvement in business regulation this past year, according to the bank’s 2014 “Doing Business” report.

Despite this progress, only 4% of rural land is registered, according to a 2014 study by the Audace Institut Afrique, an Abidjan-based think-tank.

Côte d’Ivoire’s experience highlights the perils of property rights law on two fronts. Ignoring de jure property rights can be the root of land disputes that mushroom from localised discontent into civil war. On the other hand, suddenly enforcing land laws after an era when the state actively ignored these acts to pursue its own political ends will only fuel conflict. History cannot be erased and competing ownership claims are frequently both legitimate.

Côte d’Ivoire can show leadership by continuing to strengthen property rights. These reforms should be enacted now and enforced slowly so that disaffected populations can adapt. The government should provide a one-time compensation package to those that lose their land because they cannot prove ownership, if they can prove that they had previously cultivated the land for a significant duration—even if they cannot prove that they are Ivorian citizens.

Otherwise, we will return to square one: messing with citizenship and land. We know where that leads.