The Sudans and their struggle for water

by Eric Reeves

Water, not oil, will determine the economic fate and well-being of Sudan and South Sudan. In many African countries, sewage, mud and other contaminants compromise water, health and food security. But desertification, drought and violence are crippling these two recently divorced nations.

In the Darfur region of western Sudan, government-backed militias have militarised water — seizing wells or destroying them — making this resource useless to those whose lives depend on it. Earlier in the conflict, these forces respected the neutrality of water sites, but as the war enters its second decade, the Arab militia forces, including the notorious mounted janjaweed, have increasingly denied Darfur’s non-Arabs access to water.

Providing clean water throughout South Sudan might stabilise this new nation divided by old tribal animosities. Competition for rare water sources often creates tensions that flare into violence. Peace will hold only if the government in the capital of Juba helps citizens to farm by drilling boreholes, for instance, and providing other tools useful for irrigation. The country’s oil reserves, while lucrative, will eventually run out and the government must commit fully to agriculture as the mainstay of South Sudan’s economy.

So far the record is not encouraging. The government is dithering about restarting the Jonglei Canal project, nearly completed when civil war broke out in 1983. The project would work to drain much of the Sudd, the great swampy region in South Sudan’s centre through which the White Nile meanders northward. It would straighten the Nile into a deep canal to increase the flow speed and thus significantly decrease water lost to evaporation. Such a redirection of the Nile waters, however, may have enormous environmental consequences on agriculture, fishing and wildlife. In the meantime, no other projects have emerged.

South Sudan and Sudan have suffered from cyclical droughts and floods, but Sudan is confronting other equally acute water issues related to colonial-era treaties, desertification and war. For example, construction of the Merowe dam (2003–2009) has over the past decade displaced tens of thousands of residents from Nubia, a region straddling northern Sudan and southern Egypt. This disastrously conceived dam on the Nile’s fourth cataract, a turbulent and forceful stretch between Aswan in Egypt and Khartoum, Sudan’s capital, has led to massive silting. This has forced the evacuation of farmers and fishermen who once relied on the fertile Nile and now live on agriculturally barren lands.

Other disasters are in the making. The Blue Nile, which joins the White Nile at Khartoum, Sudan’s capital, provides 75% of the waters reaching Egypt. But the construction of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam might reduce this amount and could be the catalyst for war between at least two countries. The threshold at which the perceived loss of water might lead Egypt to respond militarily is murky; but Egyptian determination to protect its most vital national resource — by military force if necessary — is crystal clear.

Recently, Egyptian leaders publicly threatened to close the Suez Canal to ships carrying supplies for the dam’s construction. Off the record, two Egyptian politicians were inadvertently heard on live television calling the dam a “declaration of war” and suggesting that forces or jet fighters be sent to destroy the dam or scare the Ethiopians. A third politician called for Egypt to support rebel groups fighting the government in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia’s capital. While these views do not reflect Egypt’s official stance, the incident left no doubt that Cairo will not tolerate what it sees as a threat to its national security.

Egypt and Sudan are the main beneficiaries of a 1959 agreement that divides the uses of the lower Nile between the two countries. Saudi Arabia is siding with the Sudanese regime in Khartoum, which offers Saudi investors lucrative agricultural opportunities that depend on the current terms of Nile water usage. But South Sudan and other countries of the greater upper Nile valley object to this treaty; Burundi, Democratic Republic of Congo, Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania and Uganda claim that the treaty has dammed their domestic water development projects.

Desertification and 10 years of ethnically-targeted displacement and destruction in Darfur have devastated vast swathes of arable land. The Sahara desert is slowly moving south through the Sahel by as much as 100 km each year. One estimate is that some 200,000 square kilometres have already been affected to varying degrees.

But Sudan’s ruling National Islamic Front/ National Congress Party (NIF/NCP) does little to halt this advancing encroachment. Water needed for farming and raising livestock, the primary means of livelihood for a large majority of Darfuris, has all but vanished. Access to water has emerged as one of the defining features of the Darfur war.

The drying up of old grazing lands once shared by Arab pastoralists and African farmers led to the Fur/Arab war of 1987–1989, Darfur’s first ethnically-defined conflict. The non-Arab or “African” Fur are Darfur’s largest tribe. The population’s cultural fault lines, however, are more complex than a simple “Arab/African” ethnic split. Arab pastoralists and militias, especially those from North Darfur, have increasingly appropriated and assaulted the lands and water sources of the Fur, Massalit and Zaghawa — African tribes perceived as the strongest supporters of the Darfur insurgency.

The long-standing grievances of these groups, coupled with marginalisation and anger at government-backed assaults on their water sources, exploded into armed rebellion against Khartoum in 2003. In response, the janjaweed riders and regular Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) dumped human and animal corpses into wells and poisoned the water. They shattered irrigation systems and slashed groves of mature fruit trees. Air and ground forces crushed hafirs, traditional earthen, underground water reservoirs used to preserve rainwater.

Unable to survive without water and fearful for their lives, more than two million people fled and sought refuge in eastern Chad or camps for internally displaced persons in Darfur itself. Left without maintenance, traditional water systems and farms collapsed. To rebuild the hafir system, re-drill the wells and replant the thirsty trees are enormous tasks. Should peace come, there is no comprehensive plan to address these needs.

Perhaps the Darfur conflict’s most disturbing feature is the militarisation of wells, wadis (riverbeds that contain water during the rainy season), hafir, and other water sources. In the past it was competition over land that defined conflict, and pastoralists and farmers shared water as a communal resource. This has changed to a war over water.

While intense destruction of water resources marked the earliest years of the conflict, many remained communal, especially those outside villages. This sharing has disappeared in the past two to three years, according to a regional expert (who requested anonymity because of his fear of the regime and desire to return to the area). Now Khartoum’s armed forces and rebel groups increasingly control water points militarily, he reported. The livestock of Arab nomads, which consume vast amounts of water or spoil it with defecation, are pushing aside the human needs of non-Arabs, evidence of Khartoum’s continuing counter-insurgency in Darfur.

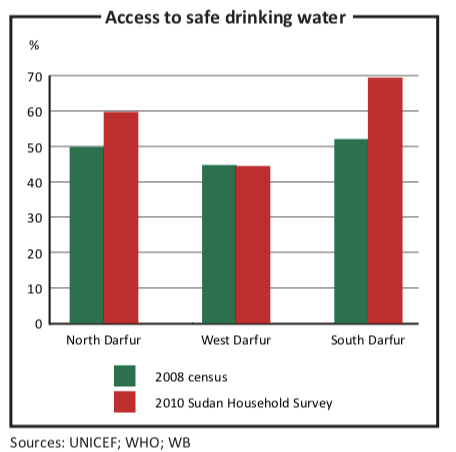

In the meantime, more than to two million refugees live in burgeoning and squalid camps outside el-Fasher, Nyala, and el-Geneina, the capital cities of North Darfur, South Darfur, and West Darfur. Their need to build housing has led to a steep demand for water-thirsty bricks, and water tables are dropping dangerously near many camps.

Soon they will dry up and there will not be enough to provide minimum daily water requirements for ever-growing populations, as in the Zam Zam camp outside el-Fasher and the Kalma camp outside Nyala, according to camp leaders and many humanitarian officials who asked not to be named.

Khartoum has made matters worse by expelling or harassing humanitarian organisations responsible for water, sanitation and hygiene. In March 2009 the Sudanese government banished Oxfam UK, the International Rescue Committee, Médecins Sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders) and 10 tother organisations. Other aid groups face financial pressure as donors grow impatient of supporting efforts against a crisis that seems to be without end. Other charity agencies have withdrawn because of intolerable security risks, including murder, kidnapping, rape and car hijacking.

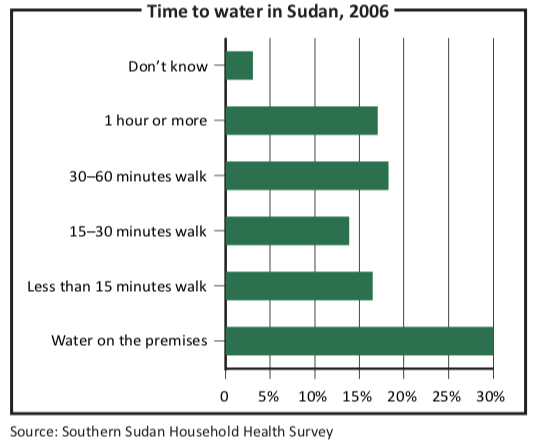

Khartoum’s expulsion of international relief organisations has exacerbated West Darfur’s water problems. Water pump maintenance has broken down and fuel and other supplies for these pumps are becoming increasingly hard to find, according to reports from camp leaders in Darfur’s three states. The distances that refugees travel for water grow longer and more dangerous, especially for women and girls. The further they travel from camp, the more vulnerable they become to rape and other attacks. The findings of groups such as Physicians for Human Rights in 2009 (the latest of such reports) provide compelling and detailed descriptions of rape. They make clear that this has become a primary weapon of war.

Unless a credible government is established in Darfur, these problems will worsen. Civil society and rebel groups do not trust the current Darfur Regional Administration (DRA). Khartoum has refused to provide the DRA with the financial and security guarantees it promised to extend in the July 2011 Doha Document for Peace in Darfur. This has crippled whatever potential existed previously for the DRA.

The water issues in Darfur and elsewhere in Sudan, however, cannot be deferred.

Khartoum has squandered extravagantly on its military over the past 24 years. Defence spending exceeded 20% of government expenditure in 2010, according to Business Monitor International, a London-based risk consultancy. Khartoum must now recognise that its neglect of the agricultural sector generally, and water supplies in particular, has been at tremendous national expense.

The dearth of investment in water development over decades, the absence of oversight and growing shortages have ensured the nonexistence of short- or medium-term solutions. Only immediate and concerted planning will preserve what little water is left. The current severe downturn in the Sudanese economy, a contraction estimated by the IMF at over 11% since 2012, makes the necessary commitments unlikely — and reveals yet again the terrible costs of war in this troubled land.