African women and girls in poor communities, forced to walk long distances to fetch water, run the daily risk of rape, beating and even death.

It was a day like any other last December. Hasiya (not her real name) had to go to fetch water from the Uke River. It is the main source of water for many in the Uke Bus Stop community in Nasarawa State, in Nigeria’s middle belt region. But the 80-minute to-and-fro trip did not quite end like other days.

The 16-year-old said, “I had gone out to fetch water in the evening. It was past 5pm already, but I was sure I would make it there and return before it got too dark. There was no water in the house and my mother had already started cooking supper. “I had fetched my bucket of water and was heading back home, when I noticed a group of about five boys sitting by a fence. As soon as they saw me, they began whistling and calling out to me. My heart was pounding as I prayed that … what had happened to other women in the community, would not happen to me.”

Hasiya ignored them and tried to increase her pace, but the weight of the 20-litre bucket of water on her head made it difficult for her to move quickly. She had conflicting thoughts. The first was her fear of being raped. The second was that she might have made a wasted trip. Having walked 40 minutes there and already halfway through her return trip, she dreaded the thought of having to go back to refill her bucket and begin the journey all over again.

But before she knew it, the young men had surrounded her. “They kicked my right leg. I fell down with my bucket of water. I was screaming for help, but I knew I was at their mercy. The road was lonely and it was getting dark too. They pulled my cloth wrap down and started beating me.” Hasiya’s pleas fell on deaf ears – but unexpected help was near. “From nowhere, we heard a motorcycle coming. As it drew closer, they saw the headlight, and they ran away. The motorcycle rider had saved me, and took me home.”

From December through February it is dry and hot, and finding water becomes an evermore time-consuming task. The time it takes to find water can endanger the young women in the area, especially during the harmattan, the dry season. “If we want to get clean water, we have to dig the ground and wait for some time for the water to gather before we can scoop it out with bowls to fill our buckets,” says Nana Adamu, a member of the community.

In recent years, conditions for the women have got worse with every harmattan season; the women have to dig deeper and wait longer for the water to gather. Having time on their hands, they find it useful to do laundry and have a bathe in the river while they wait for their buckets to fill, says Adamu. “But when we stay late at the river, these boys attack us,” she told Africa in Fact. According to the International Water Association, women in sub-Saharan Africa bear the main responsibility for fetching water in 62% of households, compared to men (23%), girls (9%) and boys (6%).

The women of the Uke Bus Stop community are among them. Though they are tasked with most household chores, collecting water makes them vulnerable to rapists because they often have to walk some distance from their homes to find it, says Water Empowerment, an organisation that focuses on reducing the time women and girls spend collecting water. Adamu has lost several buckets narrowly escaping such attacks, but she says a neighbour in the Uke Bus Stop community was not so fortunate.

“She was raped and has had to move out of the community [because of] the shame and stigma, especially as she was a married woman.” Bitrus Amadi, who is considered to be one of the elders of the community, has watched the negative development with deep concern. Last year (2019), he says, a girl from the neighbourhood was raped on her way to fetch water by a group of boys who “accused her of wearing a red shirt without their permission. This thing happened in broad daylight.” Amadi says the community has stopped reporting cases of rape to the police.

“Nothing was happening,” he says. Now, as a precautionary measure, the women only go to the Uke River between the hours of 8am and 1pm, and always in groups. Sexual assaults were not always a part of the water-fetching narrative of women from the Uke community, says Mary Amadi, who has lived there for about 10 years. “The river was not this far from us,” she says. “When I came here as a newly married women, we went to the river three to four times daily. It took us only about 15 minutes to walk there and about the same time to come back.”

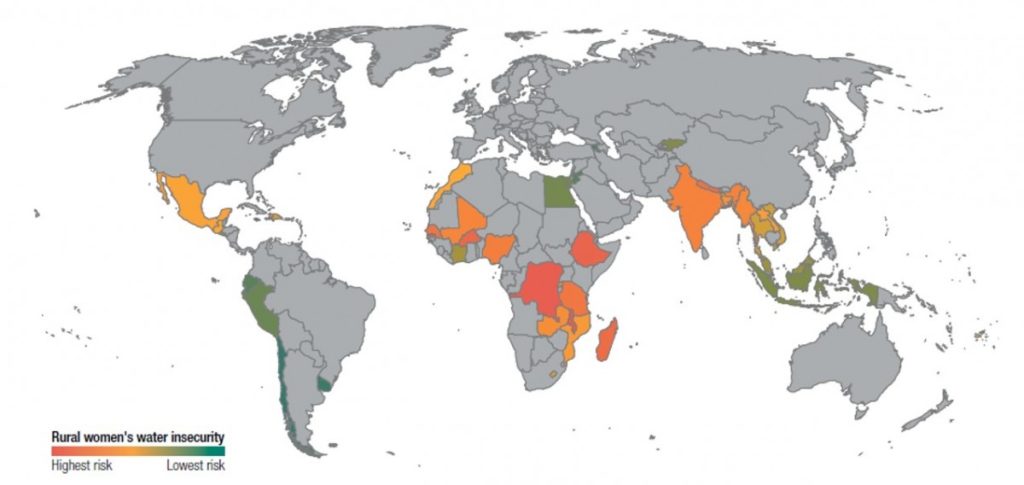

Rural women’s water insecurity

These trips were looked forward to back then because they were a social gathering and gossip time for the women. But, she says, the population has grown and buildings have sprung up, with some people channelling their sewage into the river. The river level has also dropped. Now, she says, people do not go out in the evening. “If you want water and there is electricity, you go to the one borehole we have and pay N15 ($0.38) to get 30 litres of water.” Her household uses 210 litres daily. She adds that, “If there is no electricity, you wait until the next morning, to join the queue if you don’t get there before 7am, before you can get water.

As a woman and a mother, you pray that at such a time there is no emergency that would warrant your needing water because if there is, you are in trouble.” The experience of the women of the Uke community is not new in Africa, and it is not unique. Across the continent, in West Darfur in 2015, health clinics treated 297 rape victims in five months, 99% of whom were women. About 82% of the women were raped “while pursuing ordinary daily activities, such as searching for firewood or thatch, working in their fields, fetching water from riverbeds or travelling to the market,” according to a Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF) report of that year.

The stories illustrate how climate change is having an “overwhelming” negative impact on women’s security, says Dr Priscilla Achakpa, an Abuja-based environmental and gender activist originally from Benue State in Nigeria’s middle belt region. “If a woman doesn’t get water to cook, the husband doesn’t understand why she didn’t get water. That can lead to violence.” But it is not only the daily task of fetching water that endangers women, she adds; they also face these risks while farming, which for many women is their source of income.

In many cases, for example, women may also be struggling with farmlands that are no longer fertile. These are issues relating to climate change that also affect them, and it can result in conflict. A major problem, says Achakpa, is that climate change is a new phenomenon to many women in low-to-middle income countries, and they have little or no information about it – including on how to improve their farming practices. “For most poor women, a source of clean and affordable domestic water and safe and private sanitation facilities that can be reliably accessed are key elements of sustainable development,” said Asa Regner, then Deputy Executive Director of UN Women, during her 2018 address at World Water Week, in Stockholm.

For many women in Africa, having access to this basic resource, under Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 6 (access to safe water and sanitation) is key to their achieving improvements in the areas of life covered by many other SDGs, especially SDG 1 (end to poverty), SDG 3 (good health and wellbeing), SDG 4 (quality education), SDG 5 (gender equality), SDG 8 (decent work and economic growth), and SDG 11 (sustainable cities and communities). Meanwhile, the women of the Uke Bus Stop neighbourhood say there’s an obvious way to solve many of their problems: the government just needs to drill more boreholes for their community.