The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) is blessed with millions of hectares of fertile land, plentiful rainfall and perennial sunshine. It could be Africa’s breadbasket. Yet people there are hungry.

by François Misser

Rotten leadership, two devastating civil wars and smouldering rebel skirmishes, have left nearly 50m, or three-quarters of the DRC’s population, hungry.

Yet the DRC boasts 75m to 80m hectares of arable land that could feed a billion people, according to Thomas Kembola Kejuni, a former secretary general at the ministry of agriculture. But only 10% of this potential is tilled.

The population scrapes by on insufficient imports which are distributed poorly. The DRC’s national statistics institute estimated that 21m people were affected by food insecurity in 2008. The United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) provides even more pessimistic figures: between 1990 and 2006 the number of undernourished people nearly quadrupled from 11.4m to 43.9m. The hardest-hit areas are the provinces of Maniema in the central-eastern DRC, Katanga in the south and South Kivu in the eastern DRC, Mr Kembola says.

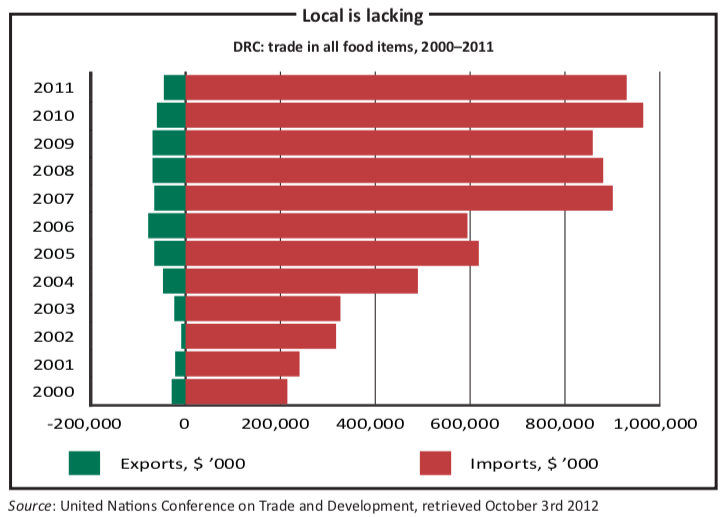

And the situation is deteriorating as population growth of 3% a year outstrips agricultural production growth of 2% a year, Mr Kembola adds. At the current pace, the DRC’s population will grow from 66m inhabitants in 2010 to 116m in 2025, while the rate of food dependence from imports is expected to increase from 25% to 40%.

In addition, undernutrition, or prolonged low levels of food consumption which provides less than minimum energy requirements, is rising alarmingly. The average minimum energy requirement per person is about 1,800 calories (kcal) per day, according to the FAO. In the DRC, however, the average level of calories per person fell from 2,200 per day in 1970 to 1,600 per day in 2007, say two Kinshasa University agronomists, Charles Kinkela and Roger Ntoto.

The dramatic collapse of the Congo’s agricultural production is the immediate cause of this nutritional disaster, according to Messrs Kinkela and Ntoto. Cassava, an edible root, is one of the DRC’s most important staple crops. Its output fell from 482.9kg per person between 1970 and 1979 to 267.9kg between 2000 and 2007. Rice production fell from 8.62kg per person to 3.77kg, whereas maize production stagnated at around 20.5kg per head. Congo, self-sufficient in beans and palm oil in the 1970s, has become a net importer. Sugar imports soared from 18,531 to 94,125 tonnes between 2000 and 2007.

Messrs Kinkela and Ntoto blame this collapse on “bad governance”, the withdrawal of foreign aid in 1992 after repeated human rights violations by Mobuto Sese Seko, the former dictator of what was then Zaire, and the devastating consequences of back-to-back civil wars in 1996–1997 and 1998–2003.

Professor Grégoire Ngalamulume Tshibue, from the Advanced Institute of Rural Development of Tshibashi in Kananga, also blames the government. “The agricultural sector has suffered for decades from the lack of a clear, coherent and voluntarist policy,” he says. Academics and donors also stress that agriculture accounts for barely 1% of the national budget, despite the commitment made by the DRC and other African countries in the 2003 Maputo Declaration to raise the figure to 10%. This year the government raised its agriculture allocation to 3.4% of the state budget, but farmers’ organisations still consider this insufficient.

Food aid and misguided trade policies, which permitted food imports at below domestic market prices, also damaged local agriculture, claims Philippe Lebailly of Gembloux University in Belgium. Insufficient financing and technical skills as well as poor farming also contributed to the DRC’s low food production.

To make matters worse, the soil is nearly barren and farmers do not have the means to fight parasites, says Adrien Kalonji, a phytopathologist at the capital’s University of Kinshasa. This may lead to yield losses of up to 30%, he says. A fungal infection known as “candle disease”, which first appeared in 1972, continues to spread because peasant farmers lack the technical skills to protect this staple crop. Cassava mosaic disease, a virus once under control before independence in 1960, is now reappearing. It could wipe out 90% of the cassava crop, Kalonji adds.

Another infection, coffee wilt disease, appeared in 1983 in the eastern DRC province of North Kivu. But now it has spread to plantations in the Equateur province, in the western DRC, 1,000km away. Another disease caused by the import of seeds without proper phytosanitary control, it is devastating maize crops in Katanga.

Congo’s catastrophic road network makes it nearly impossible to move crops from farms to markets. Food conservation, storage and processing are nearly non-existent. Maize and crops often rot because they are poorly stored, says Professor Paul Malumba from the University of Kinshasa’s agricultural industries department. Only 9% of the population has access to electricity, eliminating the possibility of cold storage.

How can Congo feed its people? Mr Lebailly suggests investing in education and promoting agriculture which focuses on expertise and fertilisers. Adding duties to imported food to make it more expensive than local produce might help too, he said. But the European Union, a major trading partner, is pushing the DRC and other African countries to sign free-trade agreements. The former colonial masters would likely block higher tariffs on their exports.

Land ownership is another stumbling block. It is the root of many conflicts, particularly in the eastern Kivu provinces, where politicians, the military, rebel militias and businessmen are scrambling for farmland and other natural resources, such as tin, tungsten, tantalum and gold.

Late last year Joseph Kabila, president of the DRC, introduced a new agricultural law, which creates a development fund, addresses wildlife and environmental concerns and sets up a new arbitration procedure to settle land conflicts. Yet the new law has no provisions for its implementation or its enforcement.

The new agricultural law’s Article 16 is another worry, particularly for foreign investors. It stipulates that land may be owned only by DRC citizens or private entities whose shares are either owned by the state or by Congolese citizens. This could mean that foreign owners of agricultural land will be forced to sell their shares, keeping at most 49%.

This “indigenisation” or “Congolisation” law seeks to prevent land grabbing by Asian (read Chinese) and other foreign companies, according to Michel Lion, a Belgian lawyer with the Brussels-based Belgian-Congolese Friendship Association. It is reminiscent of a disastrous land programme promoted in 1973 by Mr Mobuto, who “Zairianised” land and industries by giving them to his relatives and friends. These cronies often lacked the expertise to run the farms or firms and many collapsed later.

So far, only Belgians have managed to obtain concessions precluding the new legislation from applying to the companies they have already established in the DRC. For instance, George Forrest, a Belgian copper and cobalt mining tycoon who owns 44,000 head of cattle and a rice company, is protected. Likewise, the companies owned by William Damseaux from Belgium, which include a food import-export company and six ranches with 13,000 head of cattle, are also not affected by the new law.

Congo’s giant agriculture potential—enough to feed the entire continent— is dwarfed by a lack of political will to feed the country’s hungry. Without that, the cycle of civil unrest, armed conflict and displaced persons will continue to deprive this country of food and prosperity.

[author] [author_image timthumb=’on’][/author_image] [author_info]François Misser is a Brussels-based freelance journalist who has been covering Central Africa since 1981. He has worked with BBC Afrique radio and his stories have been published in African Business, Afrique Asie, South Africa’s Business Day and The Star. [/author_info] [/author]