Conflict and urbanisation

Post-conflict governments endanger reconciliation and reconstruction when they ignore or flatten their swollen cities

Conflict in sub-Saharan Africa in the past few decades has not only devastated rural villages and created sprawling refugee camps, it has also transformed the cities and towns where terrorised peasants have sought safety and opportunity.

Though the sprawling slums created by unplanned urban growth may be visible from the offices of state authorities and international aid providers, these organisations have not addressed the link between conflict and urbanisation. This neglect compromises post-conflict reconstruction, squanders opportunities for development and risks breaking an often fragile peace.

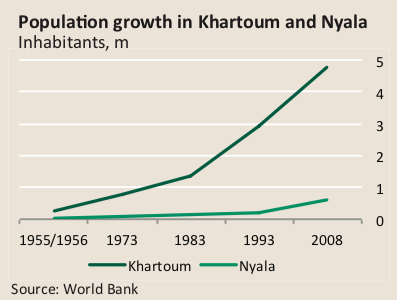

While measurements of urbanisation rates in conflict-affected countries are mostly unreliable, given the poor quality of demographic data collected in these areas, the growth is evident in specific cities. The population of Sudan’s capital Khartoum, for example, has exploded from an estimated 250,000 in 1956 to more than 5m today, according to the UN’s population division. Since the late 1970s, the arrival of people fleeing conflict, combined with natural disasters and rural poverty, have driven this growth, according to a 2011 World Bank study.

Similarly Nyala, in Sudan’s Darfur region, almost tripled in size from 230,000 people in 1993 to 630,000 in 2008, according to Sudanese census data. The Sudanese Ministry of Urban Planning and Public Utilities estimated in 2009 that as many as 1.3m people were living in the city—the disparity reflecting the volatile nature of urbanisation in the region. Nyala has swelled primarily through the settlement of internally displaced persons (IDPs) fleeing Darfur’s conflict and drought and attracted by the services provided by aid agencies, such as the UN High Commissioner for Refugees and World Food Programme, in camps in and around the city.

“Urbanisation in Sudan and South Sudan has been very much driven by different waves of displacement and return,” said Irina Mosel, a research fellow at the Overseas Development Institute (ODI), a London-based think tank. “People leave rural areas because of persistent insecurity or lack of services and employment opportunities.”

After the 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA), which ended the decades-long north-south civil war, “many returning IDPs and refugees made Juba [South Sudan’s capital] their initial stopover or transit point on their way home, but then never left,” Ms Mosel added. “They thought that conditions in their home areas were not yet conducive for return. Juba has at least doubled, if not tripled in size since 2005.”

Urban growth often accelerates further after conflict, which places great strain on governments and new and old residents, explained Tom Goodfellow, a lecturer on urban politics at the University of Sheffield. “Cessation of a civil war means that roads come back into use; it’s much easier to mi- grate; the prospects of urban employment look brighter; and village environments where everyone knows everyone else’s business suddenly look rather unappealing,” he said.

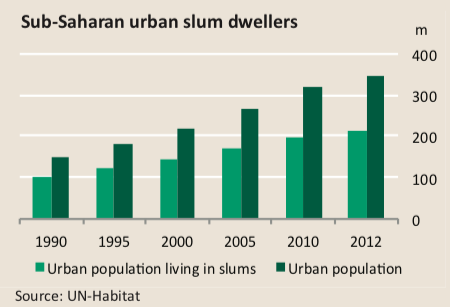

Squalid informal settlements ring many of Africa’s towns and cities: 62% of sub-Saharan Africa’s urban population live in slums, according to a 2013 report by UN-Habitat, the United Nations agency for human settlements. Despite the difficulty of living in these shantytowns, people remain because cities for the most part offer better services and economic opportunities than rural areas.

They also stay because of less tangible benefits, like the freedoms provided by liberal social norms in cities. For example, women are often more financially independent in cities and reluctant to return to the countryside, where patriarchal traditional authority presides, according to the ODI’s 2010 research on urbanisation in Sudan.

“Many young people are attracted to the urban lifestyle,” Ms Mosel added. They come to Juba looking for jobs or “hoping to start a small business as mechanics or boda boda [motorcycle taxi] drivers”.

The population of Goma, a small city in the eastern Democratic Republic of Con- go (DRC), is estimated at 850,000, which includes 93,500 IDPs, according to 2013 figures from the UN Office for the Co-ordination of Humanitarian Affairs. However, an internal survey by the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC), an independent NGO, claims this estimate is low because it excludes IDPs not living in camps or with host families. In addition, 30% of the respondents never intend to return to their rural homes, added Laura Phelps, an NRC advisor. “Even though they are living in fairly bad conditions— with poor security of tenure, doing petty trade, and often hosted by local families—they don’t want to return to their homes,” she added.

Many local and national governments have reacted with denial or outright hostility to the rapid and unsightly growth of regional capitals. For example, the governor of the DRC’s North Kivu province, Julien Paluku Kahongya, announced last May that IDPs who are “not vulnerable” must return to the rural areas, according to press releases from the UN and news agencies.

South Sudan’s leaders, after decades of civil war, responded to unchecked urban growth aggressively. “There was no strategy in place to deal with expansion of over- crowded informal settlements, especially after the CPA,” Ms Mosel said. “The [interim] government’s initial way of dealing with sprawling urban settlements was to demolish the informal settlements and forcefully relocate people to other areas.”

Most of these people moved to non-demarcated plots outside the city with even less access to services. By 2010, under pressure from the international community, the transitional authorities stopped the demolitions, Ms Mosel said.

South Sudan’s moves are not unique. Governments in conflict-affected states are in denial that they need to manage their rapidly-changing towns and cities. The need to end the conflict deflects pressure on them to do so.

But this denial becomes more obvious when the fighting ends and governments must take responsibility for reconstruction. Luanda, Angola’s capital, grew rapidly during its civil war which ended in 2002. In the midst of the post-conflict oil boom, the government has repeatedly demolished slums in Luanda over the last 12 years. The shortage of affordable housing and serviced land is huge. “The problems of post-conflict urban governance are the conflicts of general urban governance writ large: basically housing, service delivery, infrastructure and jobs,” Mr Goodfellow told Africa in Fact.

Sadly, post-conflict governments cannot provide these services in the short term, Ms Phelps ad- mitted. “Even if they did want to acknowledge the situation, they don’t have the economic and political ability to meet these populations’ needs,” she said. “They simply don’t have the funds available.”

Meeting these needs, however, requires more than money. Urban development unfolds through the fragile and complicated negotiations of post-conflict politics. “Build- ing the political coalitions needed to really bring about transformation may be much harder if there are groups that deeply distrust one another,” Mr Goodfellow said.

Government inability or unwillingness to provide urban services in the post-conflict period can lead to renewed violence and “civic conflict”, such as protests over the lack of service delivery or competition over urban resources, argued Mr Goodfellow and Ms Beall. Recent examples include riots in Maputo over food price rises in 2008 and 2010 and transportation fare increases in 2012.

Denialism will cost African cities dearly. Urbanisation offers governments greater economies of scale for delivering services as population density means sewers, hospitals and roads can reach more people at a lower cost. But benign neglect, or worse, violent evictions, will compound the problems of bad planning and unserviced sprawl.

Coming up with constructive solutions is tough for cash-strapped conflict-riven states. It requires political will and deserves the international community’s support.