Africa’s growth and foreign investment resist the world recession

by Christopher Pala

Sub-Saharan Africa has weathered the current global recession. Its growth remains resilient with increasingly diversified flows of foreign investment, according to economists and academics.

“The recent crisis that impacted Europe and the United States so hard has largely spared Africa,” says Punam Chuhan-Pole, lead economist for Africa at the World Bank. “We expect the growth rate for Africa excluding South Africa will be 6% in 2012,” she adds. “With South Africa, that would be only 4.7%.”

(FDI) in Africa soared from $9.7 billion in 2000 to $57.8 billion in 2008 before stabilising at an average of $43 billion in 2010 and 2011, according to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. Though still a small fraction of the $384 billion invested in Asia and the $187 billion going into Latin America, Ernst & Young, a business service group, reports that the number of FDI projects in Africa rose 27% in 2011, while FDI created 162,173 jobs, 16.3% more than in 2010.

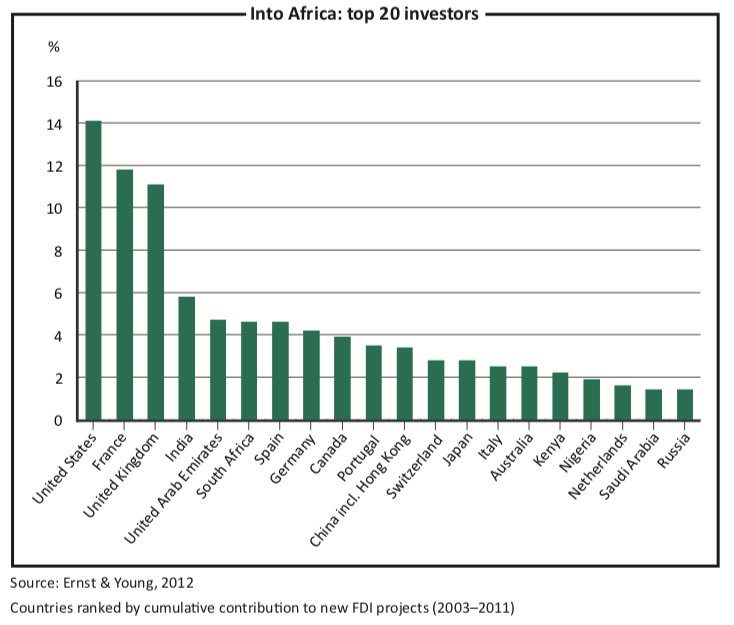

The top FDI source in 2011 was the United States with 124 projects, followed by France and Britain, says Ernst & Young’s Michael Lalor. Most of these projects were in South Africa, Nigeria and Ghana and focused on information technology, business services, communications and financial services, though US capital investments were higher for oil development projects in Angola and Nigeria. (In comparison, China contributed only 3.4% of all new projects between 2003 and 2011.)

Peter Thoms of Africa Capital Group, a California-based investment firm, believes this is just the beginning. “People are starting to understand that African growth is not a blip,” he says. “It’s one of the few places in the world where markets aren’t saturated and you can still get in on the ground floor.”

Hillary Clinton, America’s secretary of state, visited Africa in August 2012 with a retinue of executives from giant American corporations. “The days of having outsiders come and extract the wealth of Africa for themselves, leaving nothing or very little behind, should be over in the 21st century,” she said in a speech in Dakar, Senegal. The remark was widely interpreted as a jab at Chinese investors, mostly state-owned concerns which bring their own workforces and remove mostly raw materials.

A striking development in the last few years is the emergence of new investors in Africa. Other new players come from the ranks of developing nations. After the US, Britain and France, India is fourth, investing in car-making, financial services and software in such countries as Kenya, Nigeria, South Africa and Tanzania, Mr Lalor says. The United Arab Emirates is fifth, bankrolling real estate, financial services, tourism and transportation, mostly in North Africa and Ethiopia. South Africa is the continent’s sixth largest investor, with interests in financial services, communications, food and mining in Ghana, Mozambique, Namibia, Nigeria and Zambia, according to Ernst & Young.

China overtook the United States in 2009 as Africa’s single largest trading partner. “While China is also investing substantial amounts into infrastructure (generally through government-to-government agreements in return for resource concessions), private investment in greenfield or expansion projects is still relatively low, and ranks 11th,” Mr Lalor explains.

Why is Africa booming and is this expansion, the longest since the 1970s, sustainable? These were major topics at the African Studies Association meeting of 1,300 academics in Philadelphia in December 2012, reports Peter Lewis, director of African Studies at Johns Hopkins University’s Paul Nitze School of Advanced International Studies.

“Some said it was due to factors like high commodity prices that are external and reversible, and that it was driven by outside investments that could also dry up,” he says. “But others, including myself, see plenty of evidence that it’s sustainable and it has a big indigenous component, like the youth bulge in the population structure that’s producing a vibrant new class of African entrepreneurs.”

Other factors commonly cited are debt settlements, the strengthening of democratic institutions and a more business-friendly environment. A series of debt resolutions, involving rescheduling and forgiveness, took place in 2006 and permitted African countries to borrow on better terms, Mr Lewis says.

Some countries improved their rating in Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index. Between 2009 and 2012, Rwanda rose from 89th least corrupt of 180 countries surveyed to 50th. Lesotho jumped from 37th to 30th place and Liberia moved from 95th to 75th.

“Fiscal and monetary policies have improved, and so has the way many countries manage their trade, their financial sector and their business regulations,” the World Bank’s Ms Chuhan-Pole says. “All these things make their economies more efficient.” But there has been less progress on good governance and on social equity, notably property rights, accountability, transparency and corruption. Nigeria’s oil income is around $60 billion a year, and where it goes is still opaque, she adds.

“Most of the investment flow is still going to the major extractors, like Nigeria and Zambia,” Ms Chuhan-Pole points out. “But that’s not necessarily benefiting many people because most resource- rich countries are in the bottom fifth of the human development index,” which combines purchasing power with education and life expectancy. “While it’s true that many African resource-rich countries are middle income, with GDP per capita of over $1,000, most of their people still live in great poverty,” she says.

On the other hand, populations in Ethiopia, Ghana and Rwanda are seeing more progress than those in resource-rich countries and some of their economies are also diversifying faster. For the most part, this is a result of steady economic growth, a deepening of democracy, stronger leadership and falling poverty rates. “Unfortunately, diversification has been slow and a third of sub-Saharan Africa still relies on one commodity for more than half its exports,” she says.

Foreign direct investment contributes to a country’s growth and is a measure of foreign confidence. “FDI uses financing from the investing country to boost productive capacity in the recipient country, and that’s very good,” observes Montfort Mlachila, an economist at the International Monetary Fund. Investors from developing countries are playing a particularly positive role. “Unlike most American, British or French companies, these often take responsibility for building infrastructure. Brazil’s Vale, for instance, is building a railway in Mozambique’s Tete province in conjunction with a coal-mining project.”

However, he cautions: “Some recipient countries give so many tax breaks to investors that they receive fewer benefits than they could.” The Zambian government, for instance, benefited less than it could have from a big increase in copper prices, in part due to generous write-off allowances.

Whatever the mix of investors, Africa is facing its brightest prospects in decades. The continent is home to 10% of global oil reserves, 40% of gold, a third of cobalt and many other base metals. “With China and India growing the way they are,” says Ms Chuhan-Pole, “demand for these resources is not likely to drop.”