Old-fashioned radio still reigns supreme

by David Smith

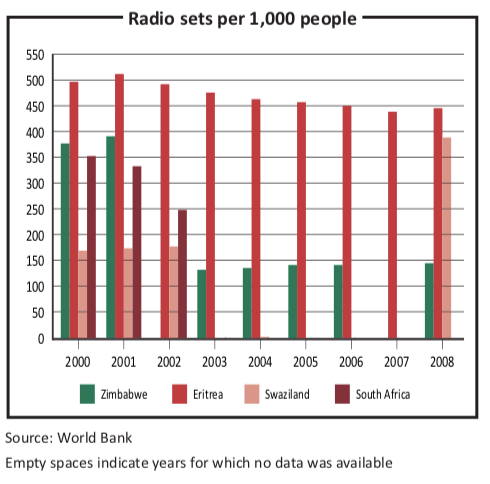

Radio threatens many of Africa’s big men. Thugs working for Zimbabwe’s President Robert Mugabe have recently been confiscating and destroying receivers. Eritrea’s President Isaias Afewerki stopped issuing import licences. Other iron-fisted rulers such as Swaziland’s King Mswati III and Sudan’s President Omar al-Bashir rarely hand out frequencies, thus reducing the range of independent radio.

The actions taken by these big men merely confirm radio’s supremacy in Africa. It may be old technology, but it is still relevant and appropriate. While not everybody owns a radio, most people have access to one.

Zimbabweans have grown adept at finding alternatives to the state mouthpiece, the Zimbabwe Broadcasting Corporation (ZBC). A combination of old and new technology permits people to hear stories that the authorities in Harare prefer they did not. Shortwave is one of the old-school tools people have counted on for decades. A number of radio stations based outside of Zimbabwe’s borders rely on reports from in-country correspondents, who use mobile phones and the internet, particularly social media, to send their reports to distant studios.

Stations such as SW Radio Africa, the Voice of the People, and Studio 7, staffed mostly by Zimbabweans, are based as far afield as Johannesburg, Washington and London. They reach their target market using old-fashioned, high-frequency transmitters originally built, for the most part, to broadcast news during the second world war.

Barely a fraction of the world’s public who listened to shortwave 50 years ago is listening today. In Zimbabwe, however, FM frequencies are restricted to the ZBC and a select few with friends in high places. But shortwave has the advantage of sending signals over vast distances, irrespective of borders and local broadcasting restrictions.

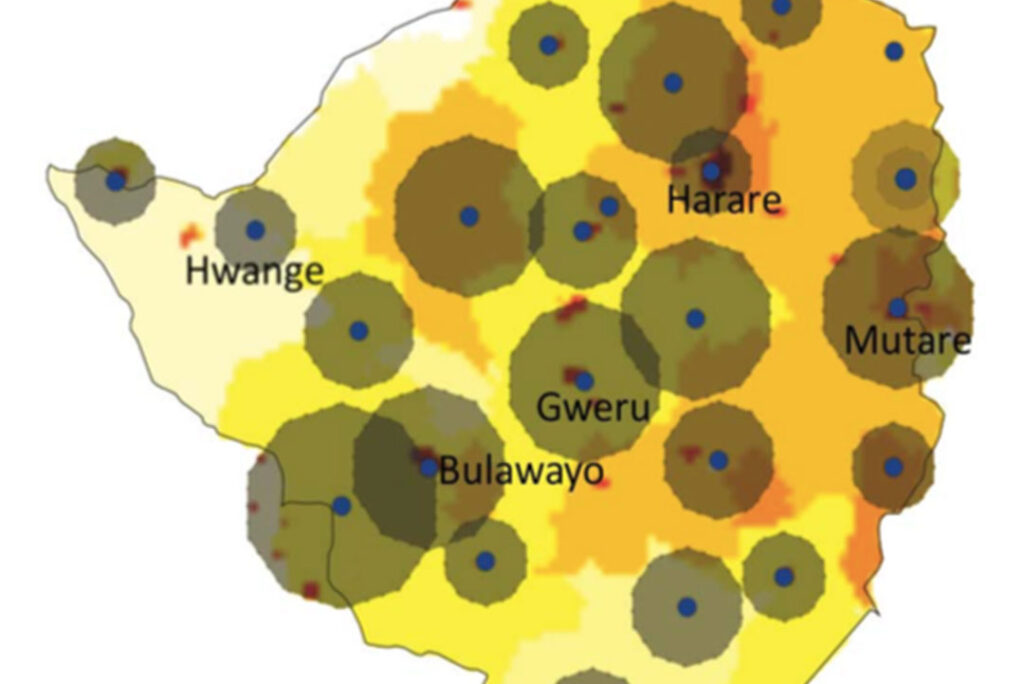

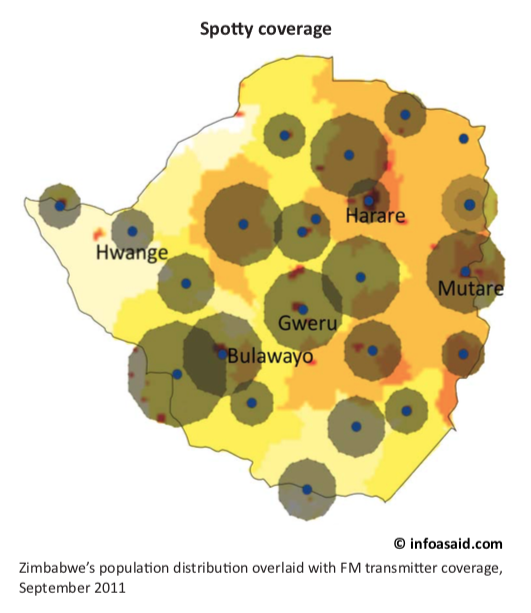

Throughout today’s modern digital world, shortwave radio is given short shrift. But in Zimbabwe, on the verge of holding presidential elections, police have staged a nationwide crackdown, declaring possession of shortwave radios illegal, without any basis in law. Radio Dialogue, a local community station based in Bulawayo, has been trying unsuccessfully for years to obtain a FM licence. Instead, it uses shortwave to send its signal around the world to an audience that is within shouting distance of its studios. Just before the constitutional referendum held in March, police raided the station and seized several dozen shortwave radios. Its manager, Zenzele Ndebele, was charged with contravening import-export regulations.

Next door in South Africa, one of the lesser-known legacies of apartheid is the near impossibility of buying a shortwave receiver. During the 1970s the National Party government attempted to dissuade South Africans from listening to foreign broadcasts, particularly ones they deemed undesirable. To satisfy the listening public, they built one of the world’s most advanced FM transmitter networks to carry South African Broadcasting Corporation (SABC) programming. A mixture of music and carefully vetted talk shows went out on African-language stations previously known as the Bantu services. Pretoria’s hope at the time was that the clear sounds of an FM signal would stop people from listening to the poor audio quality of shortwave stations such as the ANC’s Radio Freedom, the BBC World Service, Radio Havana Cuba and Radio Moscow.

Zimbabwe is not the only country where shortwave is used to bypass restrictive broadcast legislation. Pirate, or clandestine shortwave stations, often staffed by members of the target country’s diaspora, use high-frequency transmitters to send uncensored programming to dozens of countries, including Libya, Madagascar, Sudan, Western Sahara and all the states in the Horn of Africa.

In Eritrea, President Isaias Afewerki is determined not to give dissenting voices any space on the airwaves. He forbids any radio service that is not the state operator. He also places restrictions on the issuing of import permits for radios, making it difficult for Eritreans to buy the most basic of receivers in local shops.

The general public, whether in Eritrea or the remote equatorial rainforests of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), always finds ways to bypass these restrictions. The Africa services of the BBC and Radio France Internationale are filled with the voices and SMS messages of people who somehow manage to find a way of listening to banned broadcasts.

Without laying a single centimetre of copper wiring, the mobile phone has allowed much of Africa to skip landline technology and move straight to digital. More importantly, the cellphone has played a leading role in turning radio into a social tool. Radios no longer simply transmit; they also receive. The convergence between these two communications devices has created a new community and international platform for lone, isolated voices. The list of radio stations that do not have an SMS or social network relationship with their listeners, despite their location, is getting increasingly shorter. Any station that fails to interact with its public risks going the way of the dodo.

The Swaziland Broadcasting and Information Services do not tolerate content or listener comment criticising King Mswati. Social media and proximity to South Africa provide a partial outlet for his critics. On any given day, considerable traffic on Facebook is devoted to denigrating the absolute nature of the monarch’s reign. When Swazis want an update on current affairs, they do not have to listen to his majesty’s voice or the uninspiring Voice of the Church radio station. They can turn their radio dial to one of the many SABC stations that can be picked up in various parts of the country, Ligwalagwala FM and Ukhozi FM in particular.

In Zimbabwe, and to a lesser extent in Swaziland, the great thirst for credible and non-state content has strongly boosted digital technology. In virtually any part of Zimbabwe where there is a cluster of houses, chances are there will be a satellite dish affixed to some if not most of the homes. Although some of the dishes are linked to a DSTV pay-TV subscription, most are not because it is too expensive.

Instead, Zimbabweans in their millions are watching South African television and listening to South African radio using relatively inexpensive free-to-air satellite receivers commonly known as Wiztechs. South Africa’s SABC 1 and Metro FM have loyal and significant followings north of the country’s Limpopo River. Pirate radio stations have also discovered the added value satellite offers them. The infrastructure is already in place. Unlike shortwave radio, most people, especially in urban areas, have access to a dish. In the not-too-distant future it will be as easy to listen to an alternative Zimbabwean newscast as it is to watch Generations, a popular SABC soap opera.

If they want to secure an audience for the ZBC, authorities in Harare will have to do much more than confiscate shortwave radios. Expect a crackdown on Wiztechs prior to presidential elections due to be held later this year.

Video and digital did not kill the radio star. Radio is stronger than ever in Africa, thanks largely to its ability to absorb and adapt to changing technology. Deposed despots such as Libya’s Gaddafi, Tunisia’s Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali and Egypt’s Hosni Mubarak, would agree.