Two decades after apartheid

by Lucy Holborn

“It’s bad. It just is,” says Malehlohonolo Khauoe about the education she received at a rural school outside Matatiele in South Africa’s Eastern Cape province, the country’s worst-performing region. Schooling here is so inferior that the national education ministry took over its management.

This is the frontline of the education crisis in South Africa. The 19-year-old is one of its millions of victims. When pressed to describe what is so bad at her school, she says the “problem is mostly with the teachers”.

Gugulethu Xhala, 20, is from the same village but went to a different school in the area. She agrees: “Teachers sometimes just talk about whatever, nothing to do with education. They are not being monitored to make sure they are doing a good job.”

Both women have dropped out: Ms Xhala after grade 8 and Ms Khauoe in the middle of grade 11 (the penultimate year of high school) when she fell pregnant. Neither has a job and without a decent education their prospects are bleak.

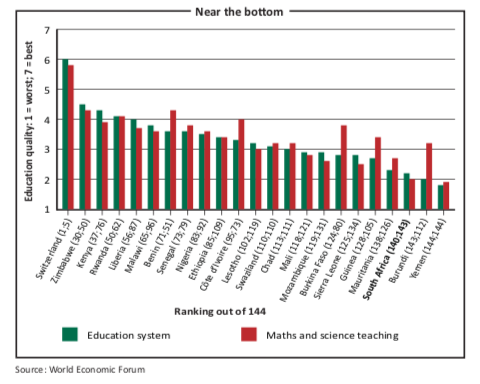

South Africa spends 20% of its budget on education, or 6.4% of GDP (considerably more than many other emerging market economies) and yet performs dismally in international comparisons. The World Economic Forum’s competitiveness index for 2012–2013 ranks South Africa’s overall education system at 140 out of 144 countries, and its maths and science education at 143 out of 144.

The minister of basic education, Angie Motshekga, denies there is a crisis. She must be blind: 1.2m children were enrolled in grade 1 in 2001, but only 44% stayed in the system to take their National Senior Certificate (NSC) in 2012. Only 12% of that grade 1 cohort ended up passing their NSC well enough to study for a university degree; and only 11% passed maths with a mark of 40% or above.

Why, then, is South Africa not reaping what it spends? Mesdames Khauoe’s and Xhala’s experiences highlight three critical factors that affect educational outcomes: teachers, the management of teachers, and outside disruptions to schooling (in Ms Khauoe’s case, falling pregnant). Jennifer Shindler, a specialist manager at JET Education Services, a non-profit research and development organisation, terms these “in-classroom factors, such as teaching and resources; in-school factors, such as leadership and management; and out-of-school factors, such as parental involvement and socio-economic circumstances”.

Teachers take the flak for South Africa’s declining education standards. “The content knowledge of teachers is a serious challenge,” admits David Silman, a director at the basic education department.

Ariellah Rosenberg, head of educator empowerment at ORT SA, a non-profit organisation that provides teacher training and skills development, agrees. “Education is only as good as your teachers, and

our universities are failing to produce quality teachers, particularly in maths and science. Teachers also have patchy content knowledge. We go to schools and find that teachers are only teaching the parts of the curriculum that they are comfortable with.”

Madelaine, 62, who asked to remain anonymous, is a teacher with 40 years’ experience in a formerly white public high school east of Johannesburg. She agrees that teachers do not know enough. Recently a department head in her school gave a test to pupils studying tourism. It asked them to name two countries in South America. Italy was among the answers suggested by the department head, Madelaine says. “A professional attitude needs to be instilled into young people entering the [teaching] profession. For many people it is ‘sheltered employment’, as they fail to meet deadlines and present quality lessons and yet are never sanctioned,” she says.

One fix would be to introduce school inspectors. The South African Democratic Teachers Union (Sadtu), the country’s largest teaching union, is opposed. Their stance harks back to a time when inspectors from the white National Party government were viewed with suspicion in black schools. “They were just there to find fault, policing teachers without playing a development role,” said Mugwena Maluleke, Sadtu general secretary, in December 2012 when President Jacob Zuma proposed reintroducing inspectors.

However, both Mr Silman and Ms Shindler suggest that much can be done even without inspectors. “There are two factors crucial in education: teachers and management,” Mr Silman says. “A well-run school will almost always have a good principal.”

School management, which largely depends on principals, is one of the “in- school” factors mentioned by Ms Shindler. Education district offices, which fall under provincial education departments, are supposed to support and monitor schools, both in administration and subject areas. However, Ms Shindler says, the districts are often understaffed and their personnel may not have the right skills. The districts cannot visit and support schools often or effectively enough to ensure good quality education.

Without well-functioning district support and monitoring, a school’s success often comes down to its principal. School governing bodies (SGBs) hire principals subject to the approval of the provincial heads of department. A well-run school is therefore likely to have a well-functioning SGB, Mr Silman says. SGBs include teachers and pupils, but a majority of their members must be parents.

However, about two-thirds of South African children do not live in the same household as their biological parents. Poverty and adult illiteracy often prevent parents who are present from getting more involved in their children’s education. “In our inter- ventions in education we are often missing the parents,” Ms Rosenberg says. “Parents play a huge role, but I think often parents don’t have the knowledge of how to help.”

The value of education in South Africa has been lost, says Jonathan Jansen, rector and vice-chancellor of the University of the Free State. It started in the 1950s with the destruction of church schools, which historically had been a source of “intellectual consciousness” in the black population, he says. The 1976 student uprising also eroded the authority of teachers and the state as providers of education, he argues. This effect can be seen today when people (including parents) blockade schools or burn libraries during community protests.

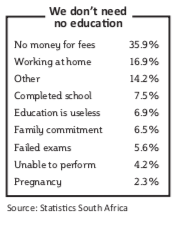

Other out-of-school factors, such as poverty, shackle the attitude of parents and society towards education. “Socio- economic factors go down through generations and starkly affect educational outcomes for children,” Ms Shindler says. Some 36% of seven to 24-year-olds are not in education because they do not have enough money for fees, according to Statistics South Africa. Family commitments, having to work at home, and pregnancy account for another 26% of those not receiving instruction. Only 7% are not in education because they consider it useless.

Many bright young people are missing out on the chance of getting a higher education because they cannot afford it, Mr Jansen says. “There are not enough bursaries for the bulge of students now coming out of the school system,” he explains, even if pupils unqualified to study for higher education are excluded.

His point highlights an area of success that is easily overlooked amid the disaster stories coming out of South Africa’s education system. Access to education has improved dramatically over the last few decades. In 1980 just 30,000 black African pupils took their matric (the predecessor to the NSC). Now over 400,000 black candidates sit the exam every year. The number of children enrolled in pre-primary schools has nearly trebled in the last decade alone.

Yet this improved access has brought with it the challenge of educating a fast- expanding school population using teachers who were often themselves the product of apartheid-era Bantu (black) education. “In criticising education policy in South Africa, people often forget the challenges that were faced after 1994,” Ms Shindler says. “The transition period involved a difficult process of amalgamating all the old education departments, equalising expenditure and distributing teachers. On the whole I think

very good policies were introduced to handle that process.” Some would disagree, arguing that post-apartheid policies have been part of the problem, in particular the frequent changing of the curriculum.

Mr Silman admits that compromises were made in this transition period, particularly in giving the provinces more power over education. “I can understand the desire after the apartheid era to decentralise power over government functions like education, but it can make it very hard for a national department to ensure that its policies are implemented effectively.”

Arguably the failures in South Africa’s education system reflect the problems that have beset governance in the country more generally since 1994. A lack of skills, monitoring and accountability have led to poor policy implementation, inferior training of teachers and bureaucrats, and a system many people have lost hope in. Those who can afford to are increasingly sending their children to private schools.

“It does seem that parents are voting with their feet,” says Simon Lee, information manager at the Independent Schools Association of Southern Africa. The number of pupils in independent schools nearly doubled between 2000 and 2012 to over 500,000. The government also does not express the same degree of hostility to the private sector as it does in other fields, such as health. A number of public-private initiatives, ranging from teacher training to the sharing of resources, show that co- operation is being embraced to the benefit of schools and pupils.

Unfortunately any solution will come too late for Mesdames Khauoe and Xhala and millions of others.