Scare tactics

Conservation hyperbole leads to poor public policy

Most professions demand formal qualifications of their practitioners. Often, the law prescribes these, but even if not, few customers would do business with unqualified accountants, engineers or lawyers.

In today’s world, there are three notable exceptions: activists, journalists and politicians. While some in these lines of work have relevant qualifications, many do not, and justify their lay status by invoking the rights afforded people in free democracies. This however makes them uniquely susceptible to making wrong risk assessments, seeking out sensational stories and basing public policy on the strength of lobby group advocacy rather than expert knowledge.

Marketing a cause often relies on exaggerated claims to counter competing causes. Scary stories sell newspapers. Public policy makers are inexpert at cost-benefit determinations. This toxic combination leads to systematic exaggeration about environmental threats, which harms, rather than helps. This affects countries with weak economies the most.

Examples of exaggeration abound. The lobby opposing genetic engineering in agriculture trumpeted a finding by Gilles-Eric Séralini, published in September 2012 in the journal Food and Chemical Toxicology. The French scientist’s study claimed to establish an increased risk of cancer in rats fed herbicide-resistant maize. After other scientists criticised that paper severely, and Mr Séralini refused to withdraw it, the journal retracted it in November 2013 as being inconclusive

. The anti-vaccine lobby bases its campaign on vague and unsubstantiated fears about the harm that immunisation may cause. For ten years it relied on a single fraudulent scientific paper by Andrew Wakefield—published in the British journal The Lancet in 1998—written while he was on the payroll of plaintiffs in a class-action lawsuit against a pharmaceutical company. The Lancet ultimately retracted it, too, in 2010, after Mr Wakefield had already been stripped of his medical licence in the UK. Even solid cases, where it is clear that environmental harm is real, support the notion that environmental risks are routinely exaggerated.

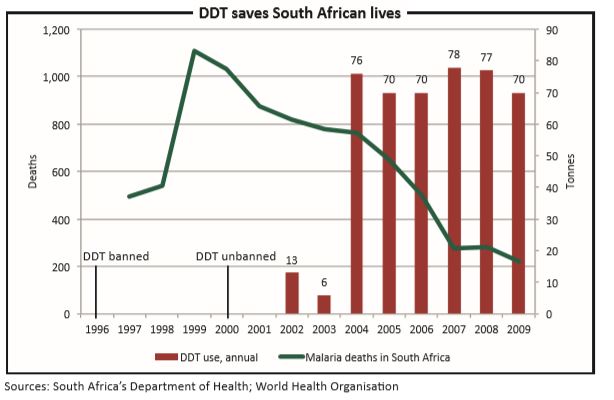

The cover of the anniversary edition of Rachel Carson’s 1962 book, “Silent Spring”, hails it as “the classic that launched the environmental movement”. Ms Carson, a marine biologist, was a prolific writer on nature who became alarmed at the environmental effects of chemical pesticides. In particular, she pointed to DDT, a highly effective pesticide that was used against many pests, including the malaria mosquito. She claimed it caused environmental harm, based on a limited study of its effects on a single bird species and anecdotal evidence of cancer in an acquaintance of hers.

Her work was instrumental in triggering the widespread ban of DDT, conveniently after the last Western country, the Netherlands, was declared malaria-free in 1971. Critics blame Ms Carson for the unnecessary malaria deaths of 50m people in the developing world, but she did not advocate ignoring insect-borne diseases merely because combating them might require chemical pesticides. She wrote: “Practical advice should be, ‘Spray as little as you possibly can,’ rather than, ‘Spray to the limit of your capacity.’” It was the exaggerated generalisation of Ms Carson’s limited findings by environmental activists that killed these people.

When the Deepwater Horizon drilling rig exploded in April 2010, it caused a massive oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico. The environmental disaster was extensive and obvious, but even so, activists found ways to overstate its impact. Researchers descended upon the area, documenting dead animals. Activists blamed every death on the oil spill. In truth, only a third of the animals they found were smeared in oil; baseline data did not exist to determine how many of the remainder died of natural causes.

Activists said oil would pollute beaches and fishing grounds as far north as the Arctic. They said fishermen in the region would never fish again. Some of those fishermen believed the exaggeration and committed suicide. The rest are back in their boats, picking up the pieces.Only a third of the oil was cleaned up. Natural degradation accounted for the remainder. What activists did not reveal is that half of the ocean’s oil comes from natural oil seeps. No one denies that catastrophic pollution is harmful. But nature is more capable of dealing with its effects than is commonly recognised.

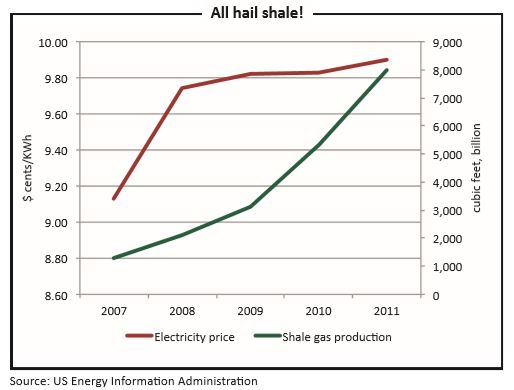

The hostility towards oil companies continues unabated. When technology was developed to profitably extract oil and gas from shale, activists went searching for cases of groundwater pollution and other environmental harm. Warnings of widespread, systematic, unavoidable and irreversible pollution were based on little more than unsubstantiated anecdotal claims and unproven scientific theories.Instead of advocating sound risk management and learning from early mistakes in pioneering territories such as the United States, activists in South Africa flatly oppose any development of the country’s potentially large shale gas reserves.

Economic predictions of benefits are also subject to exaggeration, of course, but even the most conservative forecasts predict that an abundant supply of domestic natural gas can reduce electricity prices, create hundreds of thousands of jobs and generate billions of South African rands in economic activity.None of these is possible if an entire industry is prohibited based on little but exaggerated fears. When a massive earthquake and tidal wave destroyed the reactors at Japan’s Fukushima Daiichi power plant, environmentalists warned of catastrophic and irreversible radioactive pollution. Helen Caldicott, a veteran anti-nuclear campaigner, called it “worse than Chernobyl”.

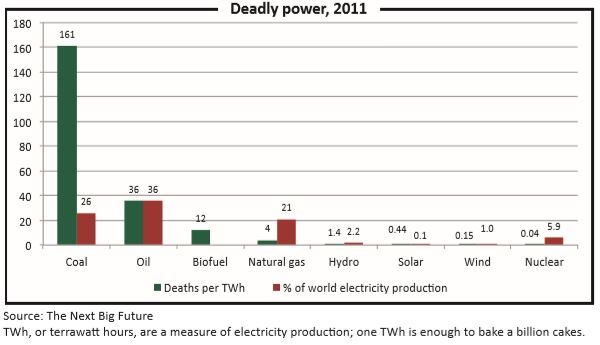

The truth is more prosaic. At Chernobyl, unlike at Fukushima, 31 people died as a direct result of the accident, all reactor staff and emergency workers. Yet even taking the 1986 disaster into account, nuclear power remains by far the planet’s safest form of energy. Counting deaths caused by mining, construction, routine operations, accidents and pollution, coal is by far the most deadly, while nuclear power kills fewer people than wind and solar power, according to statistics and epidemiological studies conducted by Brian Wang, director of research at the US-based Lifeboat Foundation, a non-profit that seeks to protect people from catastrophic technology-related events.

The fear of radioactivity, however, prompted Japan and Germany to abandon their nuclear power stations in favour of renewable energy. Both discovered green energy to be too expensive. In both countries, the decision led to rapidly rising electricity prices and had the perverse effect of a surge in demand for coal—the dirtiest and deadliest form of energy on the planet. Japan, for one, has reversed its early knee-jerk decision.

By contrast, the shale gas boom has brought massive strides towards energy independence in the US. America’s electricity is the world’s most affordable, according to a study by South African economist Mike Schussler. Unlike in Europe and Japan, US electricity prices are lower today than they were before the 2008 financial crisis.

This is relevant to emerging economies because many face similar environmental trade-offs and rising energy prices. Kenya has suspended issuing new licences for renewable energy projects as it pursues less expensive fuel sources in a drive to raise generation capacity and lower electricity tariffs. South Africa likewise faces a critical shortage of electricity, which has led to rationing for industrial users and steeply rising prices for consumers.

Many environmental activists may be able to afford more expensive but cleaner forms of energy, but the developing world cannot. The poor will not pay to put solar panels on their shacks to combat rising electricity costs. They will revert to unhealthy and dangerous sources of energy such as wood, paraffin and coal. Firms are less likely to hire new people or invest in expansion or pollution reduction when faced with rising input costs or excessive regulatory burdens.

Exaggerated environmental claims—a “crying wolf” phenomenon—are counterproductive to environmental protection. They bring about misguided public policies that actively harm economies, especially in developing nations. Ignoring genuine risks can harm the environment and human welfare, but excessive risk aversion can be just as dangerous.

Media sensationalism and political populism are powerful incentives for environmental exaggeration. These are the very institutions that ought to be able to tell the difference, but are often the least qualified to do so. Journalists and politicians with superficial environmental expertise would do well to make scepticism their default response to alarmist activist.