Meles Zenawi crafted modern Ethiopia by successfully reforming the economy while cruelly supressing dissent. His party is reluctant to loosen its stranglehold on power.

by Madeleine Fry

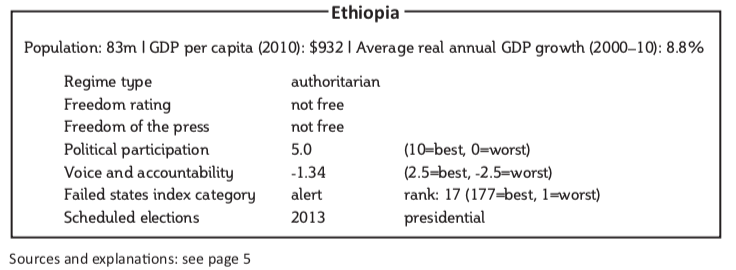

The late Ethiopian prime minister, Meles Zenawi, was quick to deny that he was a despot. Mr Meles led the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) government for 21 years and rebuilt an economy shattered by military rule and widespread famine. In the last 10 years, Ethiopia has been the fastest-growing non-oil African country. But his much-lauded economic achievements came at a price: ruthless suppression of other ethnicities and heavy state censorship of opposition media and politics.

Following the death of Mr Meles, Hailemariam Desalegn, his deputy prime minister, was appointed as prime minister. While Mr Desalegn is ethnically Woylata, control mostly sits with the Tigrayan elite that surrounded Mr Meles, himself Tigrayan. There is little interest among this elite in seeing power dispersed more widely and they will likely continue to assert major influence behind the scenes.

While the schisms and rivalries that make up the Ethiopian political spectrum have spawned over 50 political parties, representing almost every ethnic group in the country, the EPRDF’s ascendancy has condemned most to insignificance. Two opposition parties have managed to rise from the mess of inconsequence to wield some influence.

The Ethiopian Democratic Party (EDP) was founded in 1998 as a reaction against the dominance of the EPRDF. It sought to transcend ethnicity-based politics and instead emphasised the rights of individuals. It campaigned for judicial independence and private land ownership, and called for human rights and the rule of law to be more keenly observed.

For the 2005 general election the EDP formed a coalition of four parties that included the Ethiopian Democratic Union, one of the main parties to form in opposition to the Derg, the Marxist junta that ousted Emperor Haile Selassie in 1974 before being overthrown in 1991. The government ensured the limited success of this alliance, called the Coalition for Unity and Democracy (CUD). The CUD won 108 out of 547 parliamentary seats in 2005, at which point the EPRDF demanded that the country’s election board halt the counting—a move which led to allegations of vote-rigging by election monitors from the EU and opposition party members. After the CUD dissolved following the 2005 elections, the EDP reverted to its original form. It currently holds no seats.

The Unity for Democracy and Justice Party (UDJP), formed in 2008 to contest the 2010 elections, sought to campaign for greater respect for human rights and increased transparency in the country’s politics. The 2010 elections saw the EPRDF’s repressive tactics worsen. Human Rights Watch, a New York-based NGO, accused the EPRDF of systematically limiting criticism and dissent, including severe restrictions on media coverage of opposition parties. The election results saw the EPRDF take 99.6% of the seats in parliament. Opposition parties claimed that the government had actively barred people they saw as unsympathetic to the EPRDF from entering polling stations and roundly condemned the results.

The UDJP’s broad appeal makes it the party most likely to take power from the EPRDF should fair elections ever take place. As a consequence, the EPRDF government has targeted its leadership.

The party’s former leader, Birtukan Mideksa, was arrested in 2005 for questioning the results of the election and released in 2007. The government claimed she had requested a pardon to secure her release, but she denied this and was re-arrested in December 2008. After she was set free again in October 2010, she relinquished leadership of the party in early 2011 to a former Ethiopian president, Negasso Gidada.

“The major down-side to [government action against the opposition] is that it deters people at lower levels,” claims Claire Beston from Amnesty International, an NGO. “It scares them off from joining an opposition party because of the very real threat of harassment, arrest or imprisonment. Mr Desalegn has stated numerous times that he will not deviate from the path laid out by Mr Meles.”

Armed separatist groups form the other dimension to Ethiopian opposition politics. Ethnic Oromos residing in the southernmost tip of Ethiopia formed the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF) in 1973. It seeks independence from what it refers to as “Abyssinian colonial rule”. Its tactics have involved the slaughter of ethnic Amharas and Oromos unsympathetic to their ideals.

The Ogaden National Liberation Front (ONLF) also seeks liberation from what it sees as a corrupt and imperialist Ethiopian state. It demands the independence of the south-eastern region of Ogaden, an area mostly populated by ethnic Somalis, among whom they have significant support. Its armed branch, the Ogaden National Liberation Army, has been accused of attacking Ethiopian government forces residing in

the area. Unsurprisingly, Mr Meles labelled both organisations as terrorist groups.

These separatist movements indi- cate a problem as ancient as Ethiopia itself: how can the government in Addis Ababa keep together such a vast and ethnically polarised country? The EPRDF are just as unlikely to engage with secessionist demands today as they were before Mr Meles died—no matter how violent these groups get.

Although Mr Meles’s rule was antithetical to the democratic processes that are coveted by Western leaders, he found his strongest endorsements coming from these same leaders. Britain and the United States, for example, have tended to overlook Ethiopia’s human rights violations, particularly in comparison to neighbouring Eritrea. Isaias Afewerki’s regime is deeply unpleasant, backward and despotic, but this does not make Ethiopia peaceful, progressive and democratic. These attitudes help the EPRDF to gloss over continued abuses of minority groups within its borders, including the arbitary arrest by the government police of ethnic Oromos and the brutal treatment of Somalis in the Ogaden. Even with Mr Meles’s death, this foreign support is unlikely to wane. Ethiopia is seen as a bulwark of stability within the Horn of Africa, a calm centre amidst the escalating violence in Somalia and the two Sudans.

Mr Meles masterfully created a perception in the West that Ethiopia was a haven of modernity, but the loss of his powers of persuasion and the emergence of a new leadership in the EPRDF could change foreign attitudes towards the country. If Ethiopia’s economic achievements are to be lauded, its democratic failings should be criticised, for the good of the country and for the sake of the journalists, opposition politicians and human rights activists that languish in the country’s prisons.