Ethiopia presents a conundrum for proponents of free markets: despite heavy state intervention and significant limitations on civil rights, the country’s economy appears to be growing at an extraordinary pace. Kevin Bloom tries to make sense of the numbers.

To drive through Addis Ababa in mid-2012 is to be struck by the pace at which Ethiopia’s capital is reinventing itself. It is a phenomenon that can only vaguely be compared to urban renewal schemes in the West: Addis is undergoing not so much a facelift as a complete overhaul of its organs and capillaries. New highways and bridges stretch across much of the cityscape, and multi-storey structures—both commercial and residential—rise up from almost every block.

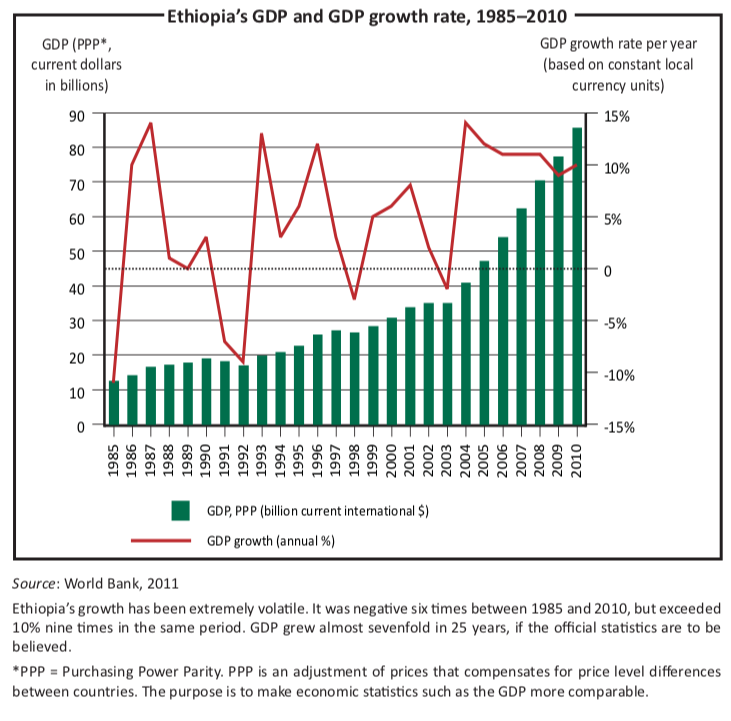

According to data out of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), between 2006 and 2011 Ethiopia was Africa’s fastest-growing non-oil economy, at an average annual growth rate of just under 10%. The construction boom and the pace of growth would appear to form part of the same narrative, a success story written by a country that has long been in need of one. Yet for every sympathiser that lauds the happy ending, there is a critic who wonders whether this new romance is not simply the old tragedy cast in an elaborate disguise.

Amongst the doubters are two distinct but important groups. On the one hand are the Western development agencies whose on-the-ground researchers have access to data that runs contrary to the official claims of the government. On the other hand are the Ethiopian “exiles,” the many thousands who have been deemed dissidents by Prime Minister Meles Zenawi and therefore watch from afar with frustration and distrust. The general scepticism boils down to one fundamental question: how can Ethiopia be growing so fast when its leader is an autocrat and an interventionist?

By all accounts, Mr Meles runs the Ethiopian economy as if it were his own personal project. His stance on how to make it thrive is no secret. In 2006 he presented a 51-page draft paper to Columbia University’s Initiative for Policy Dialogue, a project founded in 2000 by Nobel Laureate Joseph Stiglitz. The neo-liberal paradigm is a dead end, Mr Meles argued, “incapable of bringing about the African renaissance”. Instead, the prime minister proffered, if the 21st century was to be an African century, the continent needed to move in the direction of “democratic developmentalism”. Near the end of the paper, he outlined a few general points that in his estimation could lead to the successful emergence of African “developmentalist” states. He emphasised the need for foreign aid in the form of rural infrastructure schemes—specifically, the building of roads, irrigation and water-harvesting facilities.

“Rapid and sustained development in African countries will crucially depend on agriculture,” Mr Meles wrote. “It is the dynamism of agriculture which is going to determine the dynamism of the non-agricultural sector and the economy as a whole and hence determine the success of the project as a whole.”

As the numbers appeared to prove, the prime minister was not just being theoretical. According to Ethiopia’s Central Statistical Authority (CSA), cereal production in the country increased by more than 12% year-on-year between financial years 2004–5 and 2007–8, with the largest expansions coming from teff, maize and sorghum. In a nation where agriculture accounts for almost half of gross domestic product (GDP) and about four-fifths of total employment, according to the World Bank, this so-called “green revolution”—one of the fastest in history—is seen by some “happy-enders” to be at the core of Ethiopia’s incredible growth rate. The latest data out of the CSA, measuring private peasant holdings in the rainy season (September to December), asserts that the 2011 estimated cropped area and volume of production increased by 2.2% and 7.4% respectively over the 2010 season.

It is here that the government’s numbers come up against the research papers of Western non-governmental organisations (NGOs). For instance, a major study funded by the United Kingdom’s Department for International Development, published in May 2009, expressed serious doubts about the credibility of the CSA’s 2004 to 2008 yield increase statistics. “The magnitude of this growth,” concluded the authors, “and the fact it has been achieved with little change in input use, suggests something is not right with the database on agriculture.”

In brief, the compilers of the report, Stefan Dercon and Ruth Vargas Hill, argued that Ethiopia’s seed production system was not meeting yearly demand for improved product and that the fertiliser market, dominated by state-owned suppliers, did not operate efficiently—quality was found to be poor and delivery to be erratic. If the inputs were not drastically improving, the duo wondered, how could there be such a swell in outputs?

It is a difficult question to answer, and behind it lies an equally confusing anomaly. Ethiopia is landlocked and transaction costs to international markets are high, meaning that any significant rise in agricultural yields is dependent on growing urban demand within the country. This in turn implies a dependence on growth in the non- agricultural industries. As alluded to above, the obvious place to look is the construction sector.

A 2012 IMF report notes that Ethiopia’s growth is “fuelled in part by heavy public investment in infrastructure”, which is another way of saying that Mr Meles is enamoured with the Chinese model. His “developmentalist” state is essentially a version of Chinese state capitalism, in which state-directed construction companies are not a means to the end of liberal capitalism but rather an end in themselves. However, while China has seen a large and robust middle class emerging from its construction programmes—and has thus created a consumer base to fuel the economy—Ethiopia appears to be lagging considerably. As the same IMF report goes on to explain: “The sustainability of [Ethiopia’s] growth model over the medium term is uncertain, given the constraints on private sector development, the absence of savings incentives (given highly negative real interest rates), and the contraction, in relation to GDP, of the banking system. Financial sector reforms, including movement towards market-driven credit allocation, are an important priority.”

Whether Mr Meles recognises the urgency of liberalisation in the banking sector is, at this point, undecided. He holds an MBA and a master’s degree in economics, the former from the UK’s Open University and the latter from Erasmus University of the Netherlands, so he no doubt understands that an economy is doomed if people cannot get access to affordable credit. Still, no foreign banks are allowed to operate in the country. Two state-owned institutions (the Commercial Bank of Ethiopia and the Development Bank of Ethiopia) dominate the majority of lending. Also, while local- owned private banks are accounting for an ever-larger percentage of lending and deposits, the sector is closed to foreign ownership, which disqualifies Ethiopia from joining the World Trade Organisation.

Not that Mr Meles, with his abiding mistrust of Western-dominated global bodies, seems to care. In January this year, during his speech at the inauguration of the new African Union headquarters in Addis Ababa, he attributed the continent’s “lost decades” to failed internal leadership and the misdirected interventionist measures of the West. “We were given medicines,” he said, referring obliquely to the IMF and World Bank, “that were worse than the disease.” Significantly, behind him on the stage was China’s senior political advisor Jia Qinglin, whose government had forked out a purported $200 million for the shiny new headquarters, and was in all probability the real power behind Mr Meles’s economic policy.

An oft-cited catalyst for the prime minister’s autocratic tendencies, and a watershed dividing more modest growth from the remarkable figures of the last five years, is the general elections of 2005. Initially touted as the most open elections in Ethiopia’s history, with drastically enlarged freedoms for political campaigning, the months leading up to the event drew the approval of observers from the European Union and the United States. Unfortunately, the period following polling day was less auspicious— after the opposition had taken the capital and claimed to have won nationally, the government arrested its leaders and tried them for treason.

Nevertheless, in the years to come, as Mr Meles reasserted his stranglehold on the state (in the 2010 elections his party, the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front, took 99.6% of the vote), he would be censured neither by Western governments nor by his new friends in China. The former would need him as a stabilising force in a region rendered volatile by Somalia and Sudan, and the latter would stick to their policy of political non-interference. Meaning that Mr Meles, regarded by many as Africa’s wiliest head-of-state, would have a perfect opportunity to exercise his political nous. By playing off one side against the other, come 2011 his aid package would have doubled to $4 billion, chiefly from the World Bank, the United States and the United Kingdom. China, meanwhile, seeing opportunity in the largely un-serviced consumer base, would invest directly. Chinese investment in Ethiopia, according to the Ethiopian foreign ministry, stands at over $1 billion, and trade at over $1.5 billion.

And nowhere is Mr Meles’s two-pronged geopolitical strategy as obvious as it is in the construction sector. In February 2012 a cement factory worth $600m, the largest such project in Ethiopian history, was opened to service the building boom. Located 70km northwest of Addis Ababa, the factory has a yearly capacity of 2.5m metric tons. Ethiopian-born Saudi billionaire Sheikh Mohammed al-Amoudi invested $100m, with the remainder coming from the European Investment Bank, the African Development Bank, the Development Bank of Ethiopia, and the International Finance Corporation. Built by China National Building Materials Co., the project is an archetypal Meles initiative—a meeting of West and East in a context that is distinctly African.

Ethiopia’s double-digit growth figures, “dubious” as they may appear to Western media organs such as the Financial Times, could therefore be real. While agriculture’s contribution would seem to be over-emphasised, the combination of state- driven infrastructure schemes, Western aid and Chinese investment, taken against the low starting base—a 2010 GDP of $85.7 billion, according to the World Bank—is on the face of it an equation that adds up. A different matter, however, is whether such growth can be sustained.

A major side effect of the infrastructure projects that the government funds is high inflation, which in 2012 is forecast at over 33%, according to the IMF. In Addis Ababa, while the populace can now commute on highways built by Chinese contractors with Chinese loans, the bulk still live in tin shantytowns, and the cost of living leaves little prospect for upward mobility. Urban unemployment, according to the CSA, has been dropping (a national survey placed it at 18.9% for 2010), but unemployment in the rural areas is the real problem. At more than 82% of the population, according to a World Bank report released in 2011, the rural poor are justifiably a focus area for the government, yet the large-scale commercial farms that have been built as a solution do not seem to be making a fast enough dent in joblessness.

Mr Meles, meanwhile, is staying the course. A book released earlier this year entitled “Good Growth and Governance in Africa” contained an article by the prime minister, and its contents were not dissimilar to the abovementioned draft paper presented in 2006. The piece appeared under the heading “States and Markets: Neoliberal Limitations and the Case for a Developmental State”, which is evidence enough of his commitment to the vision. Still, as China’s three decades of growth have proved, state capitalism and an effective one-party system work best if corruption is kept in check, but last year, Transparency International’s annual Corruption Perceptions Index showed that Ethiopia had dropped four places, to 120 out of 182 countries surveyed.

More worryingly, Ethiopia’s current population of over 84m is expected to double by 2034, and the climate is likely to become hotter and drier—the long-term pressures on Mr Meles are therefore clear. But in the short term, if he is going to remain in power, he will need to find a way to deliver his country’s new-found wealth to its people. Oppression, as the Arab Spring of 2011 spectacularly proved, has a limited shelf life.