Writers, editors and bloggers behind bars with violent criminals

by Daniel Howden

Over the last eight years many of Ethiopia’s finest writers and editors have been collected under one roof—that of Kaliti prison in the capital, Addis Ababa. Behind its grey walls, political prisoners, including many of the country’s leading journalists, are housed alongside violent criminals.

Among them is Eskinder Nega, the 2012 winner of the prestigious PEN award, granted to international writers who have been persecuted or imprisoned for exercising the right to freedom of expression. The 43-year-old activist was unable to attend the awards ceremony as he was facing his seventh period of incarceration since he began work as an independent journalist in 1993. His wife, Serakalem Fasil, collected the prize on his behalf and was invited to the White House to meet US President Barack Obama. Their six-year-old son Nafkot accompanied her on the trip. He was born in prison when the couple were jailed for 17 months, along with hundreds of other political prisoners in the wake of the disputed 2005 elections.

The fate of Mr Nega, a prominent blogger who has been held at Kaliti since his arrest in September 2011, has become emblematic of Ethiopia’s broader struggle for media freedom.

While Ethiopia has been setting the economic pace in the Horn of Africa, posting nearly a decade of annual growth figures topping 10%, it has also collected a number of less-trumpeted firsts in censorship and repression of the media. Under the stewardship of the late Meles Zenawi, the powerful prime minister for more than two decades prior to his death last year, the country jailed more journalists than any other in Africa apart from neighbouring Eritrea. It has also sunk to the bottom of the country rankings compiled by the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), with the highest rate of exiled journalists in the world.

The state monopolises the broadcast media. The government runs all radio stations and the lone television network. More recently it has issued FM radio licenses to selected private individuals who,

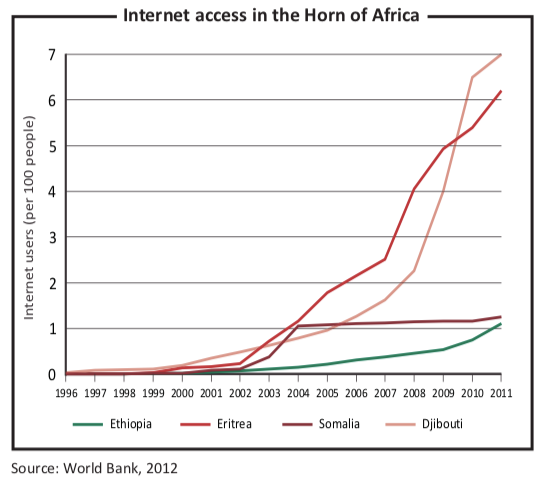

according to monitoring groups, enjoy close links to the ruling Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF). Despite physical infrastructure gains, Ethiopia has one of the lowest levels of internet penetration in the region (less than 2%). There is only one telecommunications company, which is state- owned, and mobile phone usage rates are low. Newspapers were the last trusted outlet for critical voices, with an estimated 150,000 readers in the capital with an estimated population of 4m people. But they have been closing in record numbers with 18 shut down since 2006.

Tom Rhodes, who covers East Africa for the CPJ, says Ethiopia’s media landscape has become increasingly bleak in recent years. “Most critical reporters have fled the country and the remaining independent voices are far and few.”

Ethiopia has one of the “most progressive” constitutions on the continent and one that guarantees press freedom, points out Bereket Simon, the information minister. However, this freedom exists only on paper and is restricted in practice. The international watchdog Freedom House lists the country as “not free”.

An unexpectedly strong showing by the opposition in the 2005 elections led to protests and a police crackdown in which more than 150 people were killed and thousands more arrested. Since then, the regime in Addis Ababa has shut down any space for its critics in the media. It has passed a series of laws designed to dilute constitutional protections. First came the Freedom of the Mass Media and Access to Information Proclamation in 2008, which imposed new constraints and harsher penalties on journalists. The following year came the Proclamation for the Registration and Regulation of Charities and Societies, which heavily restricted foreign funding for free media in the country.

But the Anti-Terrorism Proclamation has had the greatest impact, says Zerihun Tesfaye, formerly with Addis Neger, a leading weekly before it was closed. The exiled reporter, who now lives in the Kenyan capital, Nairobi, describes the 2009 proclamation as “the main instrument that leads journalists to self-censorship”.

Deploying vague lan- guage, the proclamation has been used for what Freedom House labels as “selective prosecutions”, including the 18- year prison sentence handed down to Mr Nega.

Much of the criticism of the statute focuses on the “encouragement of terrorism” article: “Whosoever publishes or causes the publication of a statement that is likely to be understood by some or all of the members of the public to whom it is published as a direct or indirect encouragement or other inducement to them to the commission or preparation or instigation of an act of terrorism…is punishable with rigorous imprisonment from 10 to 20 years.”

In practice, this law has placed the reporting of activities about banned groups on par with the groups’ actual actions. Among those jailed on terrorism charges is Reeyot Alemu, a schoolteacher and columnist for what had been one of the last remaining independent newspapers, Feteh. “I was preparing articles that oppose injustice,” she told the International Women’s Media Foundation. “When I did it, I knew that I would pay the price for my courage.”

Ms Alemu was arrested in June 2011 and convicted on three counts of terrorism the following January. An appeals court later reduced her sentence from 14 to 5 years. Her newspaper Feteh has since been closed altogether. Its editor, Temesghen Desalegn, has been summoned to court on a regular basis following the closure. All charges against him were dropped last year but the court warned him against any future offences. The CPJ denounced his most recent summons—where no charges were brought—as a case of: “We’ll find something to pin on you soon so watch out.”

The sudden death of Ethiopian premier Mr Meles and the appointment of the apparently moderate Hailemariam Desalegn in his stead prompted hopes in some quarters that the media restrictions might be eased. The release of two Swedish journalists, Johan Persson and Martin Schibbye, who had been sentenced to 11 years in prison for having illegally entered the Ogaden region in Ethiopia from Somalia briefly reinforced that optimism.

Remaining hopes are now pinned on Mr Nega’s appeal which, after several de- lays, is due to be heard in February. A heavy presence is expected from foreign diplomats, who hold the purse strings to some $4 billion in annual development aid to Ethiopia. The blogger, whose final column wondered if the peaceful protests of the Arab Spring might one day come to Ethiopia, will be hoping to have his sentence commuted.