Madagascar: personality trumps principle

In this poor island nation, everyone wants to be on the side that is winning

Political parties in Madagascar are often empty shells, little more than ways to legitimise individual candidates with the illusion of a broader movement. Similarly, opposition parties in this island nation are usually façades. With no ideology or platform they tend to rush to the centre of state power like moths to a flame, quickly contradicting the notion that they are in opposition at all.

The most recent experience of non-existent opposition began last year, when Madagascans voted in the December 2013 presidential run-off election. Most voters were not interested in electing either of the men on the ballot. Instead, each candidate stood as a proxy for two sidelined presidents, neither of whom was deemed eligible to run—due to a combination of technical reasons and pressure from international partners, notably the Southern African Development Community.

Coup president Andry Rajoelina—installed in 2009 after a military takeover—was deemed ineligible after submitting his paperwork after the registration deadline. The deposed president, Marc Ravalomanana and his wife, Lalao (who later sought to run in his place) were both deemed ineligible because they were still in exile in South Africa and Madagascar’s election law requires that prospective candidates reside on the island for at least six months preceding an election.

The first proxy candidate, Dr Jean-Louis Robinson, was the anointed heir of Mr Ravalomanana, the two-term president (who returned to Madagascar in October and was promptly placed under house arrest). Dr Robinson’s rival was Hery Rajaonarimampianina, the favoured successor backed by Mr Rajoelina. Given that the run-off was a proxy battle between these two men—one exiled in a coup, one that launched the coup—tensions ran high heading into the final days of campaigning.

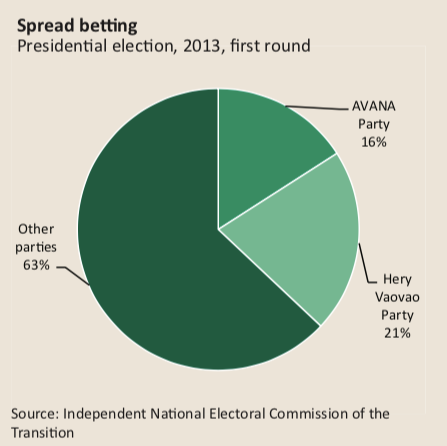

As is normally the case in Madagascar, the “parties” of both candidates had simply been tailor-made for this election and for these candidates. Dr Robinson formed his AVANA (Rainbow) Party just months before the election. Similarly, Mr Rajaonarimampianina was the founding member of the Hery Vaovao Party, a play on words using the candidate’s first name. (Hery means forces, and Vaovao means new, so the party is known as “New Forces”). Catchy, but hardly the recipe for a party based on anything other than one individual personality.

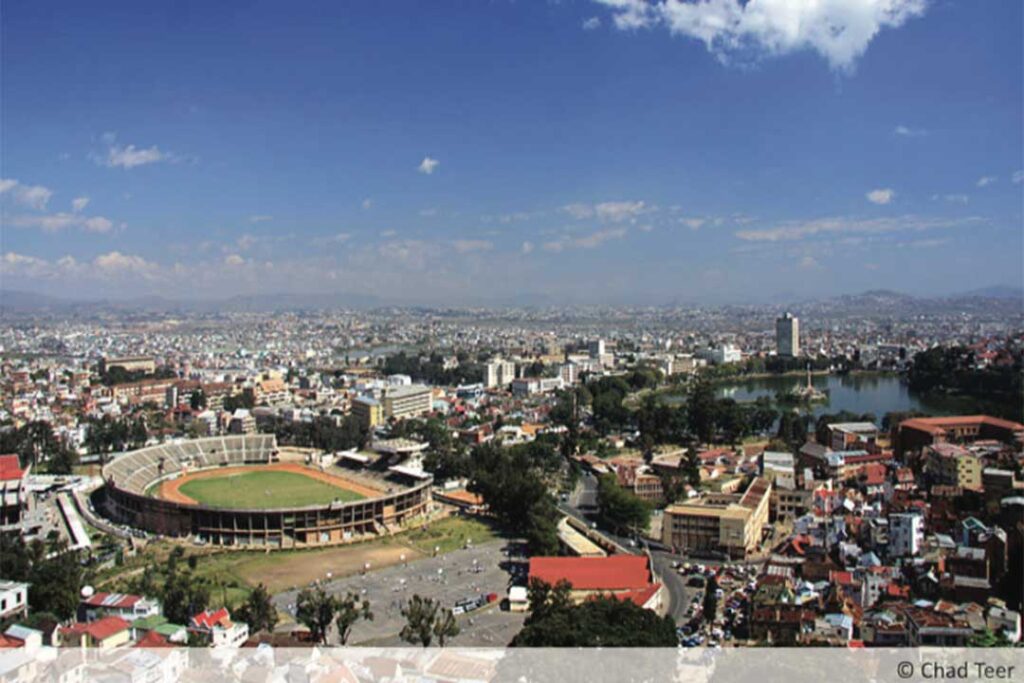

As an election observer, this author attended Dr Robinson’s faradoboka, orfinal campaign rally. It was held at the Coliseum stadium in the capital Antananarivo two days before the vote. The atmosphere was electric, as Mr Ravalomanana’s partisans found themselves on the brink of morphing from a sidelined opposition party into a powerful ruling regime.

Dr Robinson’s speech to the crowd of 15,000 sounded like a rallying call for Mr Ravalomanana, still exiled at the time. He promised the ecstatic crowd that, if elected, he would bring Mr Ravalomanana back. On campaign posters, flyers, and T-shirts, Mr Ravalomanana’s likeness dwarfed Mr Robinson’s. Across the city, at Mr Rajaonarimampianina’s competing rally, it was much the same: former President Rajoelina’s likeness not only loomed over Mr Rajaonarimampianina on banners and posters, he also stole the show by dancing on stage in front of his proxy candidate.

Neither campaign rally was remotely about policy. This was never about what either candidate would do once he was in power; it was about whom he would bring to power. It seemed clear at the time that one camp would win and one would become a fiercely antagonistic opposition party—even if their opposition was based on personality rather than principle.

Mr Rajaonarimampianina won the election two days later by a margin of 53.5% to 46.5%. Dr Robinson initially alleged widespread fraud but eventually accepted the result. Nonetheless, as inauguration day approached, the stage seemed set for a stark and possibly deadly divide between the two camps. When Mr Rajaonarimampianina took power January 25th, the inauguration was marred by a grenade attack that left a child dead and 33 wounded. It is still unclear who launched the attack or why.

However, soon after this grim omen everything changed: proxy and patron split. Mr Rajaonarimampianina, the newly elected president, was eager not simply to become a marionette. He sought to distance himself from his mentor, Mr Rajoelina, as outlined in a May 2014 report from the Brussels-based International Crisis Group, a think-tank.

As a result, in a bizarre turn of events, nearly every member of Parliament that had been Mr Rajoelina’s ally just weeks earlier—and had actively campaigned for Mr Rajaonarimampianina—now turned against the new president. Conversely, nearly everyone who had campaigned for Dr Robinson now backed the president, their formal rival. This counterintuitive inversion makes sense in the context of Madagascan politics, where political alliances are forged on the basis of power rather than policy.

Shortly after the new president took power, it was unclear who would wield real authority, the new president or the former president. Both camps, regardless of their affiliation during the election, gambled as to where state power—and the patronage that comes with it—would lie.

Over time it became clear that Mr Rajaonarimampianina had consolidated his power and effectively sidelined Mr Rajoelina—at least for the time being. As a result, there is now virtually no opposition to the regime, only petty internal rivalries in the massively big tent alliance that has become the ruling coalition, as described in the September issue of the Indian Ocean Newsletter, a regional publication.

This fluidity arises from political opportunism fuelled by 42 newly-elected “independent” candidates, who avoided affiliation with a political party simply so they could flock to the ruling coalition when it crystallised. Initially, MAPAR—Mr Rajoelina’s parliamentary coalition (the French acronym for “Friends with Andy Rajoelina”)—held the largest number of seats (49), but far from a majority.

Today, independents, MAPAR and Mr Ravalomanana’s movement all appear to be working together: the new president and his prime minister face no genuine opposition.

“In Madagascar, you could say that there is a sort of ‘winner takes all’ politics,” said Juvence Ramasy, a politics professor at the University of Toamasina on the island’s east coast. “Everyone wants to be with the winning party or at least the person in power. This shows not only the structural weakness of political parties, but also the lack of ideology in the island’s party politics.”

In some countries, like Zimbabwe, for example, the iron grip of a longstanding ruling regime has prompted the development of an opposition clearly and consistently opposed to the government. Yet in Madagascar, where opposition parties have a reasonable chance of winning elections, that fluidity of power has ironically undermined policy-based politics. Elected officials chase whoever holds the reins of power at any given time.

This toxin of flimsy opposition has consequences. With power rather than vision guiding political actors, Madagascar has made little concrete progress in the nine months since the landmark inauguration of its first post-coup leader. Opposition parties are supposed to challenge the ruling regime, exposing poor policies and proposing better alternatives. Yet Madagascar has a silent opposition, so this has not happened. At first glance, this might appear to be the sort of post-election unity many African nations would envy. In reality, it is symptomatic of Madagascar’s political disease: letting short-term pursuit of power cripple sound policy-making that could contribute to long-term stability and growth.

Policy-based visions are needed urgently on this long-suffering island. The political crisis ushered in by the coup cost Madagascar more than $8 billion, three quarters of its annual GDP and more than 15 times the government’s annual health care budget, according to a 2013 World Bank assessment. The bank’s most recent estimates suggest that more than 92% of the population lives on less than $2 per day, making Madagascar one of the world’s poorest countries.

The solution to these problems lies in finding true opposition leaders who have an alternative vision for the island. They should be committed to improving their country not through blindly praising the president but by offering dissent to his regime. Until then, good ideas and constructive criticism from a flimsy opposition will continue to be drowned out by a cacophonous chorus of opportunistic political cheerleaders.