Humanitarian aid and the media: making money from misery

by Richard Stupart

In 2004, Sudanese soldiers surrounded and laid siege to the town of Kailak in Darfur. Its residents soon began to starve and die. But somehow, foreign reporters covering the Darfur crisis failed to file stories on this tragedy. The void on Kailak’s deliberate starvation is sadly emblematic of the persistent failure of western media to shoulder its responsibilities when covering humanitarian disasters. Reporting is all too often shallow and insubstantial.

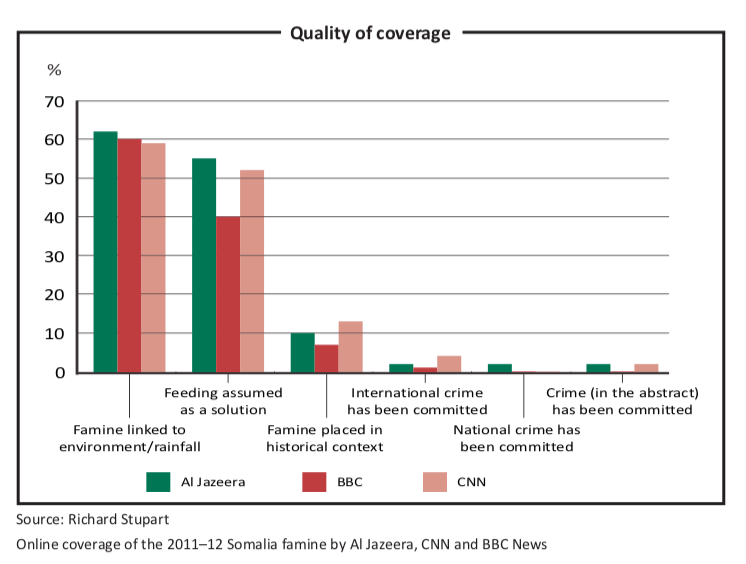

Mainstream journalism’s stories on famine, in particular, are often too simplistic. They frequently fall into stereotypical sentimentality, describing victims as voiceless and skeletal, desperately needing food, medicine and other forms of humanitarian aid. Rarely do their reports on famine question whether governments or other groups might either have provoked or prevented this hunger. Instead, newspapers and television news splash images of starving people and dire stories of how desperately food is needed. Too often, these stories are slickly-produced appeals of a “don’t ask questions, just donate”, variety.

More depressingly, an analysis of reporting on the 2011–12 famine in Somalia by television networks such as the BBC, CNN and Al Jazeera suggests that this is unlikely to change any time soon.

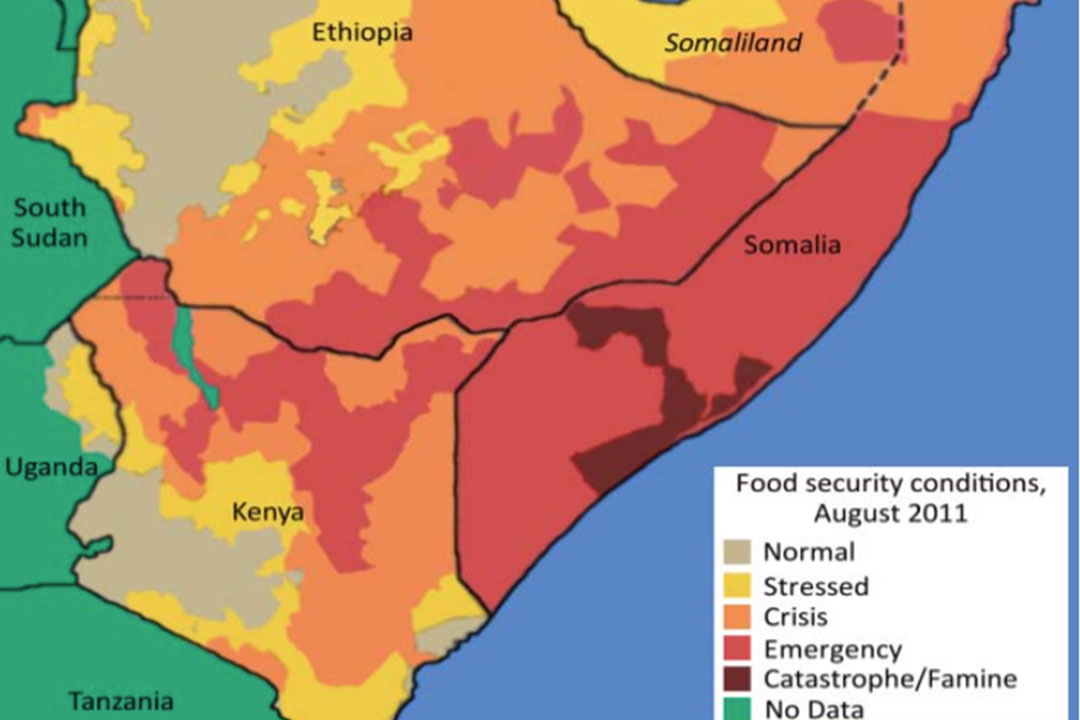

Failure of seasonal rains and reduced agricultural output were partly responsible for the famine that devastated the Horn of Africa in the past two years. But western journalists described Somalia’s hunger as the product of drought alone. This incomplete and inaccurate reporting can be blamed on laziness, a wilful misrepresentation of the region’s history and politics, or both. Ethiopia and Kenya also suffered, but saw nothing approaching the levels of mass hunger reached in Somalia. The differences in the effects of drought are so obvious that a map of malnutrition across the Horn suspiciously resembles the political boundaries of the countries affected.

To paraphrase Nobel prize-winning economist Amartya Sen, famine is the outcome of people lacking access to food and not of a food production shortage. When starvation struck Somalia, normal market mechanisms to reallocate food to areas where it was needed most — common in economies that are stable and established — failed completely. Somalia’s history is one of chronic unrest. Various groups involved in its continuous conflict contributed directly to aggravating the hunger.

Deterring disasters like Somalia’s famine requires preventive action. This means resolving the political and security issues that drive Somalia to starve while Kenya and Ethiopia survive. Enter the mainstream press and major humanitarian aid agencies: media coverage of disasters rarely stirs national governments to change their policies. Its money-spinning effect on humanitarian agencies, by contrast, is significant. As a result, NGOs have increasingly solicited newspaper, radio and television coverage, confident that positive reports boost public donations, according to Simon Cottle of Cardiff University and David Nolan of the University of Melbourne.

It is a lucrative strategy. French charity Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), winner of the 1999 Nobel peace prize, is probably the most celebrated example. It is the world’s largest recipient of privately-donated aid money, taking in donations of $1.1 billion in 2010 alone. If it were a country, MSF would have the third-largest humanitarian aid budget after the US and the UK.

Philip Brown of the economics department at Colby University in the US and Jessica Minty of the Analysis Group, an American economic consulting firm, examined donations to seven aid agencies in the wake of the 2004 tsunami that devastated south-east Asia. Their study indicated that one minute of additional television coverage on the evening news broadcast of CBS (a US television station) was worth $94,920 in additional revenue to key aid groups.

Humanitarian agencies often make big bucks when the media gives significant attention to a disaster, turning it into what Toby Porter of Oxfam GB describes as a “noisy emergency”. This effect has been understood since the 1984 famine in Ethiopia that gave the world Live Aid. In 1984 Oxfam stepped in to help after receiving a frantic telegram from BBC reporter Michael Buerk: “Help…need urgent advice on where I can leap in and out quickly with pictures of harrowing drought victims etc, to be edited and satellited [sic]…money no object, nor distance, only time.” Inspired by the media attention to the famine, Live Aid produced a musical broadcast that was watched by 1.9 billion people and raised $80 million in donations.

The sooner a disaster is covered — and the longer media attention persists — the more money aid agencies collect. The corollary, as noted by Virgil Hawkins of Osaka University, is that disasters with a poor media profile attract little funding. In 1999 Los Angeles Times reporters Anne Simmons and Christian Miller remarked on this phenomenon in comparing the levels of reporting and aid between Kosovar refugees and those in African disasters: “The allocation of aid per refugee to this intensely covered conflict was 11 times greater than that for Africa — refugee camps for Kosovars had basketball courts, supermarkets, and some had a higher ratio of doctors per person than many communities in the US.”

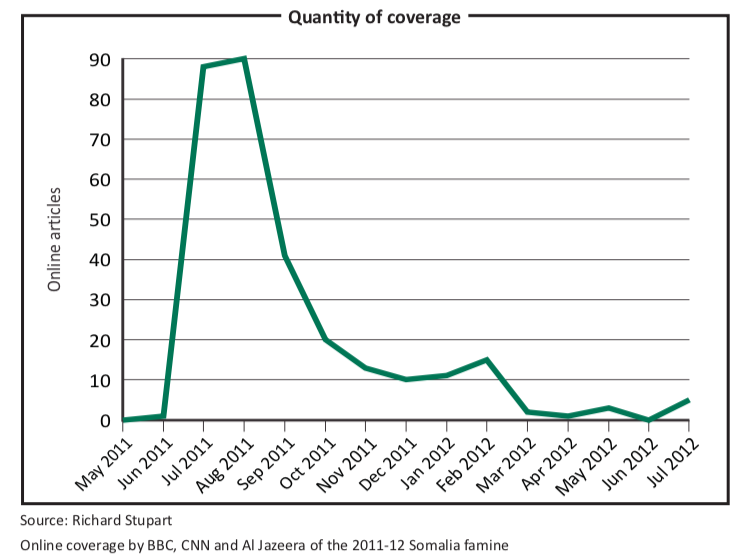

In the case of Somalia’s recent famine, early warning systems had revealed signs of food shortages months in advance. But a timeline of BBC, CNN and Al Jazeera’s online portals shows minimal coverage of the Somali famine before the middle of July 2011. Then at a press conference on July 20, the UN declared the hunger in Somalia a famine. Thereafter, media coverage exploded, only to slump a few weeks later. As former BBC Africa editor Martin Plaut explained: “Frankly, the British media are only going to be interested for a week. After that they aren’t interested. So then it gradually tails off.”

If media exposure determines the extent of public funding for humanitarian agencies, the non-existence of press reports during the early stages of a disaster should be troubling. By the time the Somali famine became a cause célèbre, it required much more funding than it would have done if journalists had reported on it earlier.

Also, the media concentrated almost exclusively on drought as the trigger of the famine, rather than on Somalia’s historic instability. Scant space was given to the criminality of the Shabaab, a militant Islamist movement, in denying communities the ability to move to cities to seek food. Nor was there much focus on the transitional federal government, whose troops were caught looting grain warehouses for profit.

If famine is to cease in places like Somalia, history and politics should be pondered in providing humanitarian aid. Parties involved in directly exacerbating the famine — the Shabaab in Somalia and the Sudanese government in Kailak in 2004 — should be named and exposed. Such coverage could coexist with calls for food donations. For the most part, it does not.

As long as media reports on disasters are late and provided without historical context — as with the 2011–12 coverage of famine in Somalia — humanitarian responses will be inadequate, short-lived and superficial. Long-term, pre-emptive solutions will also remain elusive.