PARTNER CONTENT

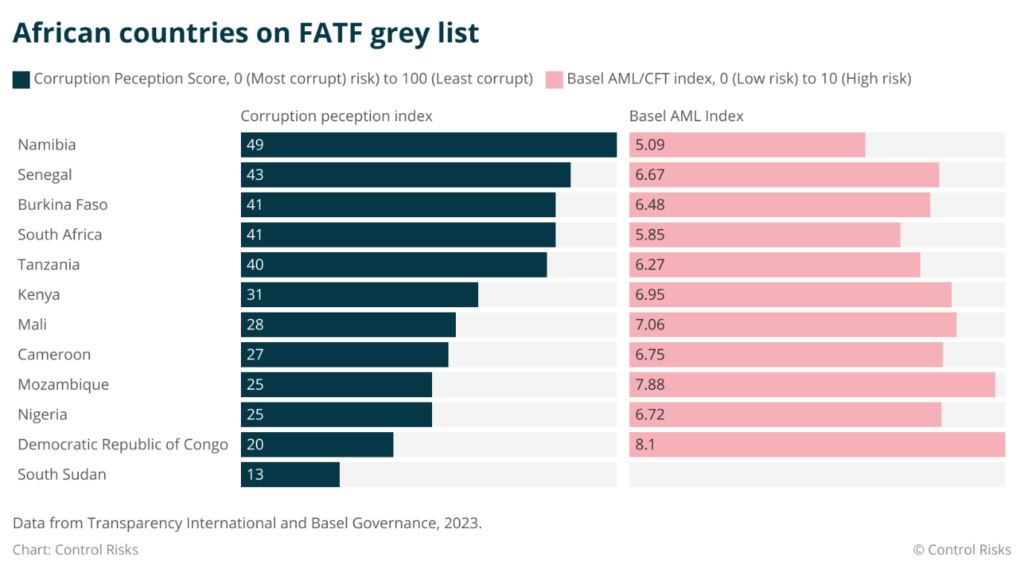

Kenya and Namibia were added to the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) grey list on 28 February, joining 10 other African countries considered by the world’s Anti Money Laundering (AML) and Combating the Financing of Terrorism (CFT) watchdog to have strategic deficiencies in the fight against money laundering. Kenya’s listing is hardly surprising: the country’s booming real estate and financial services sectors have attracted criminal networks from across the region, while its proximity to conflict zones in Somalia, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and South Sudan leaves its economy vulnerable to the proceeds of terrorism and conflict.

Despite this, the decision to greylist Kenya has been controversial locally, particularly because the country has one of the most robust AML legal frameworks in East Africa. This has been achieved through an intense four-year reform process following its previous listing in 2011. By contrast, Uganda, which was delisted on the same day, has only recently made concerted efforts to align its AML regulations with international standards. This has left Kenyan authorities frustrated, particularly because the FAFTF’s delisting requirements, which centre on strengthening AML/CFT institutions and prosecutions, will be difficult to achieve due to political considerations.

Namibia was also listed for similar reasons, with the FATF citing a persistent lack of institutional capacity and investment in sanctioning money laundering, especially as it relates to corruption. In similar fashion, although South Africa has instituted major reforms since it was greylisted in February 2023, the FATF has retained the country on the list, mostly due to persistent deficiencies in its AML/CFT enforcement mechanisms. Like Kenya, South Africa’s financial services sector continues to be used by transitional criminal groups – and increasingly terrorist/rebel groups from the region – meaning that the country will need to demonstrate a real track record of sanctioning cases of terrorism financing.

These dynamics suggest that legal reforms are not enough to demonstrate a commitment to AML/CFT action, and countries that do institute these reforms risk attracting further scrutiny into the institutional mechanisms in place to implement the current regulations. Indeed, there is a greater expectation on countries such as Kenya and Namibia, which already have relatively comprehensive legal frameworks, to also address institutional weaknesses that hamper the implementation of AML/CFT mechanisms.

In most cases, the poor implementation of AML/CFT regulations in these countries results from poor coordination between different institutions, capacity constraints, and a lack of political will to prosecute. This is especially challenging when it comes to tackling terrorism financing, which requires major technical interventions on the part of AML/CFT institutions.

For example, Kenya’s Financial Reporting Centre (FRC), which is mandated to monitor AML/CFT compliance, is severely underfunded, while the Directorate of Criminal Investigations (DCI), which plays a central role in investigating and prosecuting reports of terrorism financing, faces an acute shortage of technical experts. Likewise, resource and capacity gaps within the South African Police Services (SAPS) and National Prosecuting Authority (NPA) hamper AML/CFT enforcement. The same is true for Namibia’s Anti-Corruption Commission (ACC).

These deficiencies can be attributed to the genuine financial challenges facing the three countries, which are all grappling with elevated debt levels. This means that while prioritising capacity building in AML/CFT institutions will be difficult, it is certainly achievable for the three countries over the next two years, especially given that multilateral financial institutions are likely to support the reform process.

However, de-linking AML/CFT enforcement from politics will be much harder to achieve in these countries, where, despite having more robust institutions than their neighbours, the implementation of AML/CFT provisions is occasionally subject to political interference. This makes it difficult for AML/CFT bodies, which are often subordinate to the executive, to pursue their mandate with vigour.

Outright political interference in AML/CFT investigations and prosecutions is also not uncommon in these countries and is likely a growing concern for the FATF in Kenya, where the executive has increasingly bypassed judicial authority in recent years. In Namibia, the lack of political will to prosecute is also evidenced by the protracted nature of proceedings relating to corruption, such as the country’s 2019 Fish Rot scandal, which implicated senior government officials in an allegedly irregular issuance of fishing contracts worth NAD 300 million ($7.9 million). In South Africa, sustained political interference in the security and prosecuting services facilitated large-scale corruption under former President Jacob Zuma (2009-2018), leading to “state capture”.

Addressing political interference in AML/CFT enforcement mechanisms will be a key hurdle for these countries as they endeavour to be removed from the grey list. This is likely to be especially contentious in Kenya and South Africa, where financial services regulators are also vulnerable to political interference, which, when combined with poor collaboration with law enforcement agencies, also slows CFT efforts. These issues will test the commitment of these countries to AML/CFT mechanisms, especially because they will face heavy pressure to comply with the de-listing requirements. First, the listing is likely to hamper investor confidence, especially given that it will require enhanced due diligence for any engagements with Western companies. Kenya, Namibia, and South Africa are all in a crunch to boost economic growth, meaning that there will be some genuine will on their part to address these issues.

More importantly, the IMF and the World Bank, which work closely with the FATF, will increasingly leverage access to much-needed multilateral funding to push for the reforms. The IMF has already been instrumental in pushing for recent AML reforms in Kenya, including amendments to the AML Act in September 2023 that will compel practicing lawyers to report suspicious financial transactions to the FRC. Moreover, the IMF has engaged with South Africa regarding the implementation of FATF recommendations since the country was listed in 2023. South Africa, which is less reliant on multilateral funding, is likely to require more support from the IMF to help ease the strain on public finances, leaving room for further engagement on the matter. Likewise, the IMF warned in late 2023 that poor implementation of AML regulations had put Namibia at risk of being graylisted and would closely follow institutional reforms.

Complicated reform processes

Despite these added incentives, the reform process is unlikely to be straightforward and will be complicated by political considerations. To counter the criticism resulting from this, they will rely on symbolic prosecutions of politicians and government officials for money laundering and terrorism financing – but even these will be politically motivated, especially in the case of Kenya. There is also likely to be some genuine support for prosecutions targeting “smurfs” and money mules, but asset tracing and recovery efforts will continue to be muddled by political interference. In addition, these countries will focus on strengthening AML/CFT institutions through additional regulatory amendments that may not be fully implemented. Nonetheless, they are likely to cede to pressure to increase funding for these bodies, to showcase their commitment to the reforms. Together, these concessions will enable the three countries to be removed from the FATF grey list in the next few years. The journey to delisting is likely to be longer for Kenya, where AML/CFT reforms risk facing major resistance from sections of the population, civil society, and private sector actors. However, the authorities will endeavour to be delisted within the next two years. Meanwhile, South Africa is likely to remain on the list until at least 2025, amid budgetary constraints, and as the May general elections disrupt reforms. Namibia, which has more stable institutions, might be able to obtain a de-listing by the next review, in a year or so.

Progress?

Even when these countries are eventually delisted, it is not guaranteed that the reforms will drive notable improvements in governance, at least in the short term. Institutional weaknesses will persist, slowing AML/CFT efforts. This also means that these countries will remain vulnerable to FATF sanctions in the coming years and might be listed once again, particularly if reports of terrorism financing, corruption, and money laundering intensify. The recent oil boom in Namibia has exposed the country’s vulnerability to corruption, and the country will be subject to mounting scrutiny from the FATF in the coming years and may be listed once again. The National Petroleum Corporation of Namibia (NAMCOR) will face particular scrutiny, amid growing reports of power wrangling and corruption. In the same vein, Uganda, which is hoping to begin oil production by 2025, will need to prove a commitment to enforcing recent reforms or risk another listing.

In any case, businesses that transact with these countries will still have to contend with elevated due diligence and compliance costs, which will continue to spike in response to FATF sanctions. While this may in some instances complicate the efforts to mobilise external funding for projects in these countries, this effect is likely to be temporary, at least for Kenya, Namibia, and South Africa. Investors have typically not shied away from lucrative opportunities due to FATF grey-listing, especially in countries where the authorities can show some genuine attempts to address AML/CFT shortcomings.

Rose Mumanya

Rose Mumanya is an analyst in Control Risks’ political and country risk practice in East Africa. Based in Nairobi, Rose has experience advising a wide range of actors on the regulatory, political, integrity, and security risk landscapes across the region. Rose has a strong focus on fragile and conflict-affected states, notably Congo (DRC), South Sudan, Ethiopia, Somalia, and Madagascar. She also has experience advising clients in more stable markets such as Kenya, Tanzania,

and Uganda.