In Senegal, NGOs and government work to eliminate the cutting and removal of women’s genitalia

by Jennifer Lazuta

Marieme Bamba, a 57-year-old solar engineer, said she was just a “young girl” when her genitalia were cut, maybe seven or eight years old.

“Because of the practice, there are two painful events that I will not be able to forget for the rest of my life,” Ms Bamba said. “The first was the day I was cut—I felt intense pain for more than two days and had difficulty urinating.”

The second was the day of her marriage, at age 14. “The cutter returned with a blade to open what had been sewn together, so that my husband could have sexual relations with me for the first time,” she said.

Ms Bamba is one of 140m women and girls worldwide that have been victims of female genital mutilation and cutting (FGM/C), according to the World Health Organisation (WHO). UN agencies define FGM/C as “all procedures involving the partial or total removal of the external female genitalia or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons”. It is usually performed on girls between the ages of four and puberty.

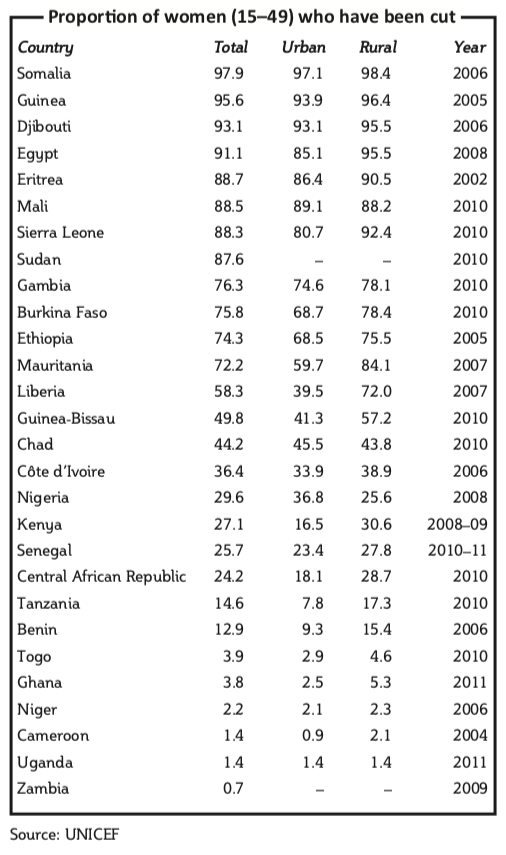

While this custom occurs on every continent, in Africa about 101m girls over the age of 10 have been cut, according to UN agencies. The prevalence of FGM/C is particularly high in sub-Saharan Africa. In Guinea and Sierra Leone, the prevalence of FGM/C is close to 100% in many areas. In countries such as Somalia, Djibouti, Eritrea and Mali, between 88.5% and 97.9% of women between the ages of 15 and 49 are reported to have been cut.

The United Nations General Assembly adopted a resolution in December 2012 that called on member countries to pass and enforce laws banning FGM/C. However, deep-rooted social, cultural and political traditions have often made it difficult for individuals to abandon the practice. Cutting is often seen as a rite of passage for girls. Many Muslims still believe that FGM/C is part of Islamic law. In many communities, girls risk being stigmatised or even shunned if they are not cut. Women are often considered ineligible for marriage if they have not been excised.

The WHO says there are no known health benefits of FGM/C. In addition to the severe pain involved with the cutting, FGM/C can cause many short- and long-term physical problems. It is considered a violation of human rights and a form of gender discrimination.

“Genital mutilation is a big health-care issue in our population,” said Dr Abdoul Aziz Kassé, a surgical oncologist in Senegal who now performs reconstructive surgery on women who have been cut. “The women often get infections, have problems urinating, suffer from chronic pain and face complications during childbirth,” he said. “Excision also creates many difficulties for them during sex.”

Ms Bamba, other activists and even the government are now joining efforts to eliminate FGM/C in Senegal. In 1998 her village became one of the first in the country to publicly declare their rejection of the custom. Since then more than 5,500 communities have stopped cutting women’s genitals in Senegal.

Ms Bamba is now part of an awareness team that helps educate other communities about female cutting, as well as human rights. The government and aid groups say that this “community empowerment” approach, which was developed by international NGO Tostan in 1991, has been key to reducing FGM/C in Senegal. The government says it hopes to eliminate FGM/C entirely by 2015.

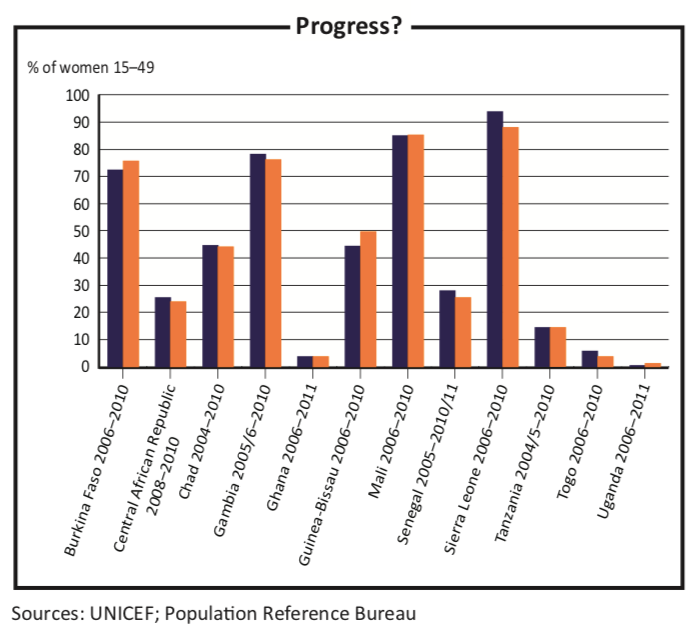

When compared to neigh- bouring countries, Senegal has scored a few victories in the fight against FGM/C. Despite a range of efforts, including the adoption and implementation of legislation out- lawing FGM/C, and massive edu- cation campaigns, the percentage of women between the ages of 15 and 49 who have been cut has decreased to 25.7% in 2010 from 28.2% in 2005, according to UNICEF, the UN Children’s agency.

“People, communities, they are now really starting to abandon this practice,” said Cissé Astou Diop, who runs the family division of the family and women’s ministry, which manages the effort to end FGM/C within Senegal. “People have begun to realise that this practice, which they thought was a good thing, is actually really harmful to their daughters.”

The government says that it has been fighting FGM/C since the 1970s. A National Committee for the Abandonment of Harmful Practices Affecting Women and Children was established in 1984. In 1999 Senegal became the seventh African country to outlaw FGM/C, after Burkina Faso, the Central African Republic, Djibouti, Ghana, Guinea and Togo, according to the UN Economic and Social Council. Today, 17 African countries have outlawed the practice, including Benin, Chad, Côte d’Ivoire, Egypt, Kenya, Niger, Nigeria, Tanzania, Uganda and Sudan.

Senegal’s penal code stipulates up to five years imprisonment for anyone who is involved in performing, arranging or assisting FGM/C. While the law was an important step forward, both the government and aid organisations say that it has really been the education and awareness campaigns—many of which are now part of Senegal’s 2010–2015 National Action Plan for the Acceleration of the Abandonment of FGM—which have succeeded in reducing mutilation.

“In terms of the law, if people really want to, they can just take their daughters next door to the Gambia, where the practice is still legal,” said Gallo Kebe, the coordinator of the joint UN population and children’s agencies programme on FGM/C, which works alongside Senegal’s National Action Plan. “What’s really important,” Mr Kebe said, “is that we teach people about the dangerous physical, psychological and medical effects, and also to focus on the human rights aspect, so that they can make informed

decisions about the practice,” he said.

Many NGOs and activists have played an important role in executing the National Action Plan, Mr Kebe said, but Tostan has been instrumental in getting communities to abandon FGM/C. Tostan developed an approach known as the Community Empowerment Program (CEP).

“You can’t just go into a community and express outrage and disgust over the practice,” said Tostan’s founder and executive director, Molly Melching. “The key to ending FGC [female genital cutting] is that you have to take everyone who matters in your family and social network, and give them the information they need to make an informed decision,” she said. “If you just come in and try to tell people—who think they are doing something good for their children—that FGC is bad, and basically inferring that they are willingly doing bad things to their children, they shut down.”

Tostan works with communities over the course of two to three years, teaching them not just about female cutting, but also human rights, democracy, health and hygiene, and women’s rights, while also reinforcing literacy, maths and management skills.

Ms Melching said that once people are armed with such information—which they probably never had before—many realise the significance of stopping FGM/C. As people begin to draw their own conclusions, Tostan facilitates a debate within the community about whether or not to abandon the procedure.

“A critical moment in this process is that when they [the communities] reach

the decision to abandon FGC, that they do so publicly,” Ms Melching said. “This is very important for making sure that people know that their daughters won’t be ostracised or ridiculed because they have not gone through the practice.”

Sister Fa, a well-known singer and a rapper, is also a FGM/C survivor. She uses music to educate young people about the mutilation of women’s genitals. “The problem right now is a lack of information,” she said. “I noticed that there were a lot of NGOs doing a great job using some kind of pedagogic way to reach the women, but that the young people weren’t really concerned about that way of working,” Ms Fa said. “And since young people are our future—since they are the ones who can stop this practice from continuing—I thought, what can I do to get this generation to change? What can I use? What will interest them? And the answer was things like music, dance, poetry, painting and theater.”

Sister Fa first began touring the country

in 2008 to speak out against FGM/C. Last month she completed her third tour, “Education Without Cutting”, and is currently at work on a new album. “With music, when you organise a concert and there’s some kind of noise, young people just come out,” she said. “They come to listen to the music, but go back home with a very strong message. It’s been a very positive way of passing along important information,” she said.

While Sister Fa has faced some resistance from village elders and religious leaders, she said her message has generally been well-received. Other NGOs, such as the Group for the Study and Teaching

of the Population, are following Sister Fa’s footsteps and targeting Senegal’s youth, too. They have been training teachers to incorporate FGM/C into the curriculum to reach more young people. Films and documentaries have also proven to be an important tool.

While most agree that Senegal is unlikely to see zero FGM/C any time soon, most are hopeful that they can come close to that goal within the next few years. “More and more people will make their declarations to abandon. That is certain,” the UN’s Mr Kebe said. “The political will is there; the financial and technical partners are there; the willingness is all there. So the partners, we will all continue to work together,” he said. “But I think, unfortunately, there will always be pockets of resistance, places where people will hold onto the tradition [of FGM/C].”

Though many communities are initially resistant to the idea of abandoning female cutting, it is important to keep on educating people, Ms Bamba said. “I call on all practicing communities, from the bottom of my heart, to abandon this practice, for the sake of everyone’s well-being,” she added.