Wave of illegal and overfishing hits Mozambique

by Megan Izen

Adelino Francisco Huo spent most of his teenage years rising before dawn and climbing aboard a dhow, a small wooden boat with triangular sails. Mr Huo and a small group of boys and men would set sail along Mozambique’s Indian Ocean coastline and cast out their wide nets. Not much later, their arms would bulge as they hauled in hundreds of flapping fish, shrimp and crab.

Ten years later and Mr Huo, 23, sleeps longer hours and no longer sails out to sea. He is now working on land at a fresh water tilapia farm in Vilankulo, a coastal town in southern Mozambique.

“In past years, fish were plentiful,” he said. “The fish are decreasing because there are more fishermen entering the ocean. Now you’ve got to have luck on your side. If you go out to fish and come back with something, it’s been a lucky day for you.”

But as local and international demand for fish increased, the marine population became scarcer in places like Vilankulo and the 700km stretch of coastline in southern Mozambique’s Inhambane province. The region’s shimmering waters are the only place in the world where whale sharks and giant manta rays coexist year round. Its exceptional marine life and reefs have made Inhambane a premier diving destination in the last decade. The province is Mozambique’s second-largest tourist destination after its capital, Maputo, according to the World Tourism Organisation.

But overfishing—by both industrial and artisanal fishermen—has led to a dramatic drop in fish and marine biodiversity and is threatening Inhambane’s reputation, according to the Marine Megafauna Foundation, a research and conservation organisation. Small dhows and giant industrial trawlers

either cast or drag nets along the sea floor and unintentionally sweep everything in their path, including

protected species. As a result, the sightings of reef manta rays have decreased 88% since 2003, according

to the foundation based in Tofo, a small town in southern Inhambane.

Overfishing is menacing fishing and tourism, two of the province’s most lucrative industries.

Artisanal fishing in Inhambane province surged from 2007 to 2011, according to a study by Mozambique’s Fisheries Research Institute. The quantity of fish caught by artisanal fishermen increased from roughly 3,000 to 7,500 tonnes per year. Fish from Inhambane’s waters are sold in African, European, Asian and local markets, according to the National Institute of Fishing Inspection.

Many artisanal fishermen are not only fishing illegally but are also clashing with tourist operators who rely on marine biodiversity to attract sightseers. Last year, tensions rose as photos of fishermen gutting manta rays and sharks on the beaches of Tofo triggered a public outcry and tourist operators worried that visitors would be deterred. Both are dependent on the fish, but the tour operators need the fish alive while the fishermen live on killing them.

Fishermen do not reap enough of tourism’s economics benefits to control or reduce their catch, said Frank Weetjens, executive director of the Association of Active Divers for Marine Resources (AMAR), Mozambique’s national divers’ association. If fishermen saw schools built with tourism dollars or tourists buying other local products like fruits, vegetables and nuts, attitudes toward fishing regulations might improve, Mr Weetjens added.

“Ultimately, they [the artisanal fishermen] were here before the tourists came,” Mr Weetjens said. “Because of this lack of dialogue, as long as these guys don’t feel a daily difference in their lives”, a solution will not be found.

AMAR is working with local fishermen in Inhambane to create a government- recognised association to protect their common maritime assets. More than 50,000 fishermen in Mozambique depend on the ocean for their sustenance and livelihoods. In Inhambane, about 400,000 people depend on the province’s more than 7,000 fishermen, according to Mozambique’s Institute for the Development of Small-Scale Fisheries in a 2012 report. About 100 tourism operators and eight diving companies are registered in Inhambane, said Raufo Ustá, the treasurer for the Association of Hotels and Tourism in Inhambane.

Divers and dive centres also have a vested interest in curbing overfishing. International tourism dollars spent in Mozambique more than quintupled from $49m in 1996 to $270m in 2011, reported the World Bank. According to a 2011 study for James Cook University in Australia, about 74% of international tourists visited Tofo specifically for the diving, a recreation at risk if illegal and overfishing persist.

Inhambane province is home to the marine big five: sea turtles, dugongs (a rare marine mammal), whale sharks, manta rays and humpback whales. The United Nations, the WWF and others list the five as endangered species. But Mozambican law recognises only two—dugongs and sea turtles—as protected species.

This has led to conflicts between divers who want to see more species protected and fishermen who have few economic alternatives. (More than 80% of Mozambique’s citizens lived on less than $2 a day in 2008, according to the latest World Bank figures.) And while Vilankulo, the area where Adelino Francisco Huo was a fisherman, has established a conservation area where most fishing is prohibited, most of the coast remains vulnerable to overfishing.

As the huge wave of artisanal and commercial fishing swelled, the fishing industry has remained anchored in regulations that are now nearly 15 years old, with scarce resources to enforce them. These laws and regulations have focused mostly on medium- and large-scale industrial operations rather than

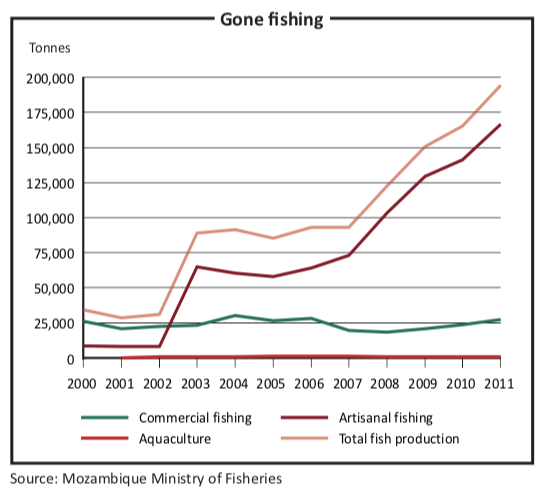

small-scale fishing, which has grown from 70% to 90% of the total industry between 2008 and 2013, according to Victor Borges, Mozambique’s fisheries minister. The tonnes of fish culled from the country’s waters rose from 122,000 in 2008 to 194,000 in 2011, according to the latest figures available.

This year the government claims it is ramping up efforts to combat illegal fishing by both unlicensed and unregulated artisanal fishermen and commercial boats. Fishing is the country’s fifth-largest export, behind timber, cotton, sugar and cashews, representing 2% of its gross domestic product, or about $225m in 2012, according to Mr Borges. In April 2013 the fishing ministry said that it would tighten regulations to protect more species by spending more money on enforcing the laws banning illegal fishing, which results in a staggering $67m a year in losses.

Rodolfo Macassa arrived in Inhambane in 1981 to establish the province’s first fisheries department. During his 30-year tenure, Mr Macassa managed artisanal fishing in the region through a civil war (which lasted from 1979 to 1992) and a subsequent boom in foreign interest in Mozambique’s marine resources, which began in 2000 when the country became compliant with international trade regulations.

Political will and resources to monitor and enforce existing laws are thin. Mozambique currently spends about $2.25m a year to combat illegal fishing, with just two boats to patrol nearly 3,000km of coastline. This is equivalent to 0.04% of its national budget for 2013. A small pile of tattered nets lies behind the fisheries department, evidence of the tiny amounts hauled in by the current regulations. Three fishing patrolmen are responsible for enforcing fishing regulations for all of Inhambane province. “It’s not enough,” Mr Macassa said.

Since the early 2000s, Mr Macassa and his colleagues have built relationships with fishermen by establishing Community Councils on Fishing (CCPs). The province’s 32 CCPs encourage local fishermen to follow fishing regulations, protect endangered species like sea turtles and dugongs, help license those who are not fishing for subsistence, as well to report violations to the fisheries department.

Self-regulation, “particularly not having the courage to report violations”, is weak, Mr Macassa said. Even when CCPs do report infractions, the authorities with the power to fine, arrest or confiscate catches and equipment often do not have the boats or off-road vehicles to arrive at the crime scene before the offenders have fled, he added.

“The growing number of [fishing] boats has created difficulties,” Mr Macassa said. “A survey needs to be done and limits need to be placed on fishing.” But controlling the industry is becoming harder each year.

In March 2011 Mr Borges complained that the country’s current statutes are inadequate because they do not adequately regulate artisanal fishing. In a report to parliament, he outlined plans to develop sustainable fishing practices and new strategies for regulating the industry. Mr Borges would like the government to encourage private fish farming initiatives, increase patrolling of Mozambique’s waters and also tighten the laws to protect endangered species.

Mr Macassa agreed that these reforms are needed to protect endangered fish as a result of the huge increase in illegal fishing and overfishing. But he said he has little hope that they will be adopted, let alone implemented. The government sometimes overlooks the country’s long-term needs to keep the support of its poor citizens, he conceded. “Policy and administrative objectives sometimes contradict each other,” Mr Macassa said. “Sometimes political forces require that limitations aren’t adhered to so that subsistence needs of the population are met.”

[author] [author_image timthumb=’on’][/author_image] [author_info]Megan Izen is a writer based in Mozambique. Her work has been published in The New York Times, GlobalPost, Colorlines.com and AlterNet. She received her bachelor’s degree in women’s and gender studies and mathematics from Sonoma State University in California and her master’s degree from the City University of New York’s Graduate School of Journalism. [/author_info] [/author]