South Africa’s water ways

The government has neglected to maintain and improve infrastructure

by Ivo Vegter

South Africa is widely regarded as a “water-scarce” country on the verge of a crisis. Should its residents worry more about scarcity or decaying infrastructure?

“If we continue using water as if it is an infinite resource, we may find ourselves in trouble,” said Edna Molewa, South Africa’s minister for water and environmental affairs during a breakfast briefing last May. There is a real possibility of “running out of clean water”, she added.

A mere day later, the same minister told parliament: “You must have heard how South Africa will run out of water in 2013, 2015, 2025 or 2030, depending on which news source you rely on,” she said. “Let me assure you, as the custodian of water resources in this country, that South Africa will not run out of water in the next 100 years.”

Ms Molewa pointed to a proposed 671 billion rand ($64.5 billion) to be spent on improving water infrastructure over the next decade, a 17% rise from 573 billion rand earlier in the year. By July, this estimate had risen by another 4%, to 700 billion rand over the next decade, of which less than half had actually been budgeted, leaving a shortfall of 385 billion rand.

Ms Molewa suggested that water price increases steeper than inflation were possible in the near future, but refrained from providing details pending a review of tariffs due to be completed by the end of this year.

Several towns and regions have already felt the impact of water scarcity. Carolina, a town in the eastern coal mining region of Mpumalanga province, was left without water after mine runoff, also known as acid mine drainage, polluted the local dam. The response was a shambles, with responsibility being shifted from local municipality, to district municipality, to the national water affairs department. Eventually, the courts had to step in to force the municipality to supply alternative water to residents, on the grounds that the constitution declares access to clean water a basic human right.

In August, Grahamstown, a university town in the Eastern Cape, spent more than a week without water, after a series of breakdowns and a power failure at the town’s 50-year-old pumping equipment. It took the intervention of the office of Jacob Zuma, South Africa’s president, to restore water to affected residents and prevent Rhodes University from shutting its doors.

Students in Potchefstroom, another academic city, were not as lucky. The North-West University sent its students home in March this year because of an ongoing and severe water shortage.

Kevin Wall, a civil engineer with the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research, told the media that a lack of expertise, poor infrastructure maintenance and an absence of political will to maintain existing systems are to blame for severe water shortages affecting towns as far-flung as Ermelo, Lichtenburg, Middelburg, Kriel, Delmas and Lydenburg in Mpumalanga and North West provinces.

These incidents suggest that Ms Molewa’s budget priorities are in the right place. However, the Worldwide Fund for Nature (WWF) does not share the minister’s faith in infrastructure development. Heavy investment in water infrastructure in the past has given South Africans a “false sense of water security”, it claims in public documents related to its water balance programme, which aims to help companies reduce water demand.

The country is rapidly approaching what it describes as “full utilisation of available surface water yields”, and simply investing in infrastructure cannot solve this problem. Instead, the focus should be on the conservation and rehabilitation of natural environments.

South Africa is indeed water scarce but decaying infrastructure exacerbates the problem, said Garth Barnes, national conservation director of the Wildlife and Environment Society of South Africa (WESSA), in an interview with Africa in Fact. “Many would say we don’t yet have a water crisis only because infrastructure has not yet entirely failed us,” he said.

As with many other sectors, most notably railways and electricity supply, the government has neglected water infrastructure in recent decades in favour of more politically urgent budget priorities. The underinvestment is starting to bite.

South Africa receives about half as much rainfall as the global average, and it is among Africa’s driest countries. Its rivers are small compared to other major watercourses in the world. The Zambezi, Africa’s fourth-longest river, alone accounts for more water flow than all South Africa’s waterways combined.

The total water that flows into South Africa’s rivers, known as “runoff”, is estimated at 49 billion cubic metres per year. Of this, only about one-fifth is required as an “ecological reserve”, to ensure that river ecosystems remain viable, according to the water affairs department’s first National Water Resource Strategy (NWRS), published in 2004. At present, 20% of this water is abstracted for use. Another 14% is lost to evaporation or land use, leaving some two-thirds of the total available runoff behind in rivers—far more than the required ecological reserve.

This suggests that the notion of “water scarcity” is not simply a matter of how much water exists at the source. The NWRS estimates that infrastructure development could increase water availability, or “yield”, by as much as 40% by 2025.

However, the second edition of the NWRS, gazetted on August 22nd 2013, contains exactly the wording the WWF uses: “Whilst we have well-developed water resources infrastructure we are fast approaching full utilisation of available surface water yields, and are running out of suitable sites for new dams.”

The new NWRS does not use updated estimates of the water supply and demand balance contained in the 2004 version to support this claim. Instead, it admits that a town survey found that “in most cases, water supply deficits are not the result of water resource shortages but rather of poor water supply management. Improved management will solve most of the immediate problems.”

The 2004 NWRS noted that of the 13.2 billion cubic metres of water available for use in the benchmark year of 2000, water requirements ran to 12.9 billion cubic metres. The narrow surplus of between two and three percentage points nominally supports the WWF’s utilisation claim, but ignores the strategy’s optimism about projects that might increase available water yield. It also ignores that 30% to 40% of water is lost between source and consumer because of ageing municipal reticulation (pipe) infrastructure, inaccurate metering and billing, and outright theft.

Ms Molewa said this is fairly typical by world norms, but her department aims to reduce these losses to 25% over the next ten years.

The agriculture sector is the largest user of water by far. Although it contributes less than 5% to GDP, some 65% of water is used for irrigation and forestry. By contrast, all mining, industry and power generation put together use only 8% of the country’s water, while individual and commercial consumers account for the remaining 27%.

Assuming that little water saving can be extracted from industry, and irrigation demand is not going to decline, plugging leaky pipes will save far more water than anything consumers can reasonably do.

The extent to which water scarcity affects South Africans does not so much depend on the total water resource, or how much that resource yields. It depends largely on where you live.

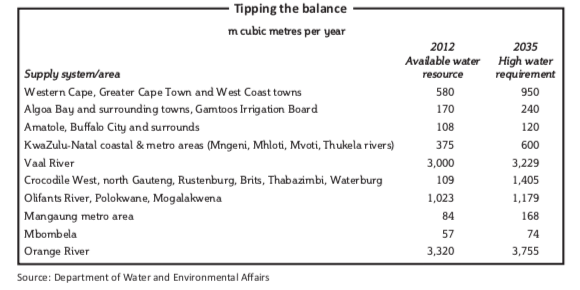

Rainfall is highly unevenly distributed. The Eastern Cape and Free State provinces have abundant water and relatively low requirements, for example. Freshwater resources in their catchment areas are underutilised. However, many other regions—including some high-rainfall provinces such as Mpumalanga—run at a deficit by tapping into stored water resources, even though a modest surplus is evident in the national figures. Under a high-growth scenario, the NWRS 2013 edition notes several regions, including the important catchments serving Gauteng and the Western Cape provinces, that will soon reach a critical level of water use in relation to available supply. The KwaZulu-Natal coastal region has already exceeded its supply by using stored water from dams faster than rainfall refills them. It relies on water piped in from other catchments.

Even within water catchment management areas, shortages may occur in smaller areas or individual towns. The latest NWRS surveyed 905 towns and reports that 30% are already in deficit and another 13% can expect to experience a water shortage in the next five years.

In addition to river systems, groundwater is a potentially significant resource. Unfortunately, given South Africa’s geology, these underground aquifers are unevenly distributed. Only about 20% can readily be exploited on a meaningful scale.

Spatial development has compounded the geographic inequality of water resources. Many towns and cities, including most famously South Africa’s largest city, Johannesburg, were established close to mineral resources rather than water. The racial segregation policies of the apartheid regime drove the development of other urban and rural areas.

This unequal distribution of scarce resources leaves consumers with fluctuating supplies. To manage this fluid resource on a national level, requires managing a complicated network of catchment areas. This makes the country unusually reliant on large-scale infrastructure developments, complex reconciliation strategies to match available supply to regions in water deficit, and international agreements such as the Lesotho Highlands Water Project.

“Provided that the water resources of South Africa are judiciously managed and wisely allocated and utilised, sufficient water of appropriate quality will be available to sustain a strong economy, high social standards and healthy aquatic ecosystems for many generations,” the NWRS declared in 2004. It also proposed sophisticated regulatory measures, such as tradable water allocations, as a market-based mechanism to maximise the benefit derived from available water supply.

But lofty declarations, complex regulations and eye-watering budgets are easier written than achieved, according to Sean O’Beirne, a director at Sustainable Environmental Solutions, a consultancy. The water affairs department is dangerously over-extended, he said. Its ability to manage and maintain the country’s infrastructure as well as oversee industrial and mining water-use licences is in doubt, he added. It is not for lack of good intentions, but because the challenges are complex, and know-how is low.

WESSA’s Mr Barnes admitted that he is “not tremendously confident” of government competence. The problem—as seen in the Carolina case—extends not only to the national department, but also to local municipalities, he added.

“The lack of capacity at [the water affairs department] is felt both in terms of numbers, but technical competence is also an issue that doesn’t inspire a great deal of confidence,” he said.

If the government’s infrastructure budget is effectively spent on upgrading ageing infrastructure and establishing new supply sources such as the proposed 20 billion rand ($1.96 billion) Umzimvubu dam in the Eastern Cape province, there is no reason why the water affairs department cannot meet promises of “sufficient water for generations”, or claims that “we will not run out of water in the next 100 years.”

However, that stipulation is highly uncertain. This may explain why the second NWRS makes much of demand-side efficiency programmes such as rainwater harvesting and reusing treated water. Recycling already accounts for some 14% of available water supply. Rainwater harvesting, while it remains expensive by volume and hard to manage from a health perspective, has been successfully used in both private and municipal settings.

“Rainwater harvesting is more of a private sphere behaviour,” Mr Barnes said, “so it’s more difficult to control from a health perspective. Through my experience with local government, there is a big push, an impetus, a will around it, especially in larger metros like Johannesburg. But it’s going to need everyone’s buy-in, and not just pockets of experts. More minimally resourced municipalities are going to struggle.”