Erasing trade tariffs, subsidies and customs agreements between countries

by Ivo Vegter

The Doha round of multilateral trade negotiations, an initiative of the World Trade Organisation (WTO), has been deadlocked for more years than negotiators have spent making progress.

Launched in late 2001 in the Qatari capital, the Doha round was especially aimed at including the developing world in the process of liberalising trade across the world. By 2006, with almost no progress made in gaining better trade terms for developing countries, it had foundered on intractable disagreements about agricultural subsidies in developed nations such as Japan, the United States and especially Europe.

Agriculture promises a significant export opportunity for the developing world. It enjoys trade protection in developed countries amounting on average to some 3% of the value of agricultural produce. Politically, these farm subsidies and import tariffs are hot potatoes. Attempts to reduce or dismantle them routinely meet with strong political opposition and sometimes even violent protest. In November 2012 proposals to cut the European Union’s budget by reducing agriculture subsidies led to protests in the countries that were the biggest beneficiaries of such largesse. Chief among them is France.

Several attempts have been made since to jump-start the talks. However, they remain firmly on ice, leaving member countries in both North (developed countries) and South (developing countries) without an apparent incentive to reduce barriers to international trade.

But is it sensible for developing countries to insist on their own trade protections, pending concessions from the rich world?

Pascal Lamy, WTO director-general, warned in May 2012 that world trade growth was decelerating. Trade in 2012 was predicted to grow about 4% in volume, down from 5% in 2011 and an average of 6% in the previous 15 years. “This 2012 forecast is mostly a consequence of sluggish growth in advanced economies, particularly in the eurozone,” he explained. “The contribution of trade to growth in emerging and developing countries is also decreasing and is forecast to further decline.”

Subsequently, in September 2012 the WTO revised even those estimates downwards, anticipating only 2.5% growth in 2012 and scaling back 2013’s growth expectation to 4.5% from 5.6%. For 2012, the WTO anticipates 1.5% growth in developed economies’ exports (down from 2%) and 3.5% growth for developing countries (down from 5.6%). Imports for developed economies are “nearly stagnant”, at 0.4% (revised sharply downwards from 1.9%), but a more robust 5.4% increase in imports is expected in developing countries (down from 6.2%). Trade analyses such as HSBC’s Global Connections Report also indicate that export and import trade volumes are growing among emerging markets.

Contrary to the rhetoric of the anti-globalisation movement, free trade does not benefit the rich world at the expense of developing countries. (Its association with broader “structural adjustment programmes” imposed on struggling emerging economies in the past, not all of which have been benign or successful, has tarnished the idea.) While particular sectors, companies or individuals—those that were protected by trade “protectionism”—may suffer from increased competition, the overall gain from free trade over autarky (self-sufficiency) in any goods or services is positive.

Columbia University economics and law professor Jagdish Bhagwati and his co-authors made this clear in “Lectures on International Trade”, where they discuss how to “measure the gains of trade”. Notwithstanding the loss in customs revenue to the fiscus, or the losses to formerly protected industries, the formulae in their textbook do not even contemplate that the measure might be negative.

Even Paul Krugman, a famed economist not known for his strong free-market views, once said: “The appreciation that international trade benefits a country whether it is ‘fair’ or not has been one of the touchstones of professionalism in economics.”

The Forum for Research in Empirical International Trade published a paper in September 2010 that examined the effects of 283 trade agreements. “Free trade agreements lead to a rise in bilateral trade even if the signatories include developing countries,” according to the United States-based research organisation’s study.

Even more notably, the percentage increase in bilateral trade is higher for South-South agreements, that is, among developing countries—than for North-South agreements—that is, between rich and poor countries, wrote the authors, Alberto Behar and Laia Cirera Crivillé, economists at Oxford University and Universitat Pompeu Fabra, respectively.

Patrick Barron, in an article penned for the economics journal Mises Daily on July 31st 2012, went even further. He argued that regulatory and monetary interventions harm only those who impose them. He provided a simple example to illustrate this idea. If a country imposes a trade tariff against a foreign competitor, or worse, a prohibition on trade, such as one might do against Chinese textiles or Iranian oil, who is really harmed?

No seller of merchandise has an inherent right to trade with anyone else, just as your local grocer cannot compel you to purchase his wares. If you prohibit yourself from dealing with that seller, you either feel no effect (if you would not have traded with him anyway) or you are forced to go further and pay more. Therefore, the effects of self-imposed trade restrictions against your trading partner can only harm you, Mr Barron argued.

Refusing to trade with the corner grocer may benefit the supermarket further down the street. The supermarket may favour regulatory intervention that certifies the grocer’s wares as somehow inferior, more expensive, or even illegal, to protect its business from competition.

Such protection, however, always hurts the consumer. Producers are nothing more than a special-interest lobby seeking preferential legal treatment—tariffs on competing products or bans on imports— to help themselves overcome competitive hurdles that would encourage customers to buy elsewhere, if they were left free to choose.

“A just economic policy for a free and prosperous nation would be based on the twin pillars of unilateral free trade and non-intervention into its own markets,” Mr Barron concluded.

This notion is not new. As long ago as 1981, Paul Wonnacott and Ronald Wonnacott, of the Universities of Maryland and Western Ontario, respectively, wrote a paper pondering what curious conditions might motivate countries to conclude such bilateral tariff reduction agreements, with all their drawbacks, when most of the benefits are available to each country by unilateral action.

The theory may be sound, but does the notion that unilateral trade barrier reduction can earn developing countries most of the benefits of trade deals with rich countries hold up in practice? There is an easy way to check: if South-South trade is significant by volume, and tariffs are higher in developing countries than in the rich world, the conclusion follows.

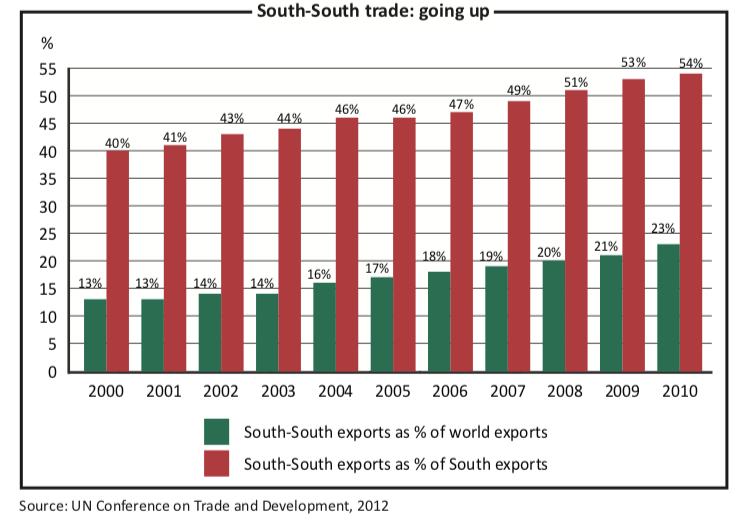

“A whopping 42% of all trade guarantees provided by the [World Bank’s trade finance programme] have so far been for projects between developing countries. It’s a sign of a gigantic trend,” observed Frank Brandmaier in an article for Global Policy Forum, a non-profit policy watchdog. “Rising economic powers like China, India and Brazil, but also smaller players like Mali or Vietnam, increasingly rely on each other in terms of trade and investment, and their ties are fast-expanding. The share of developing countries’ goods and services destined for other developing nations— known as ‘South-South’ trade—increased from 29% in 1990 to almost half in 2008, according to the World Trade Organisation.”

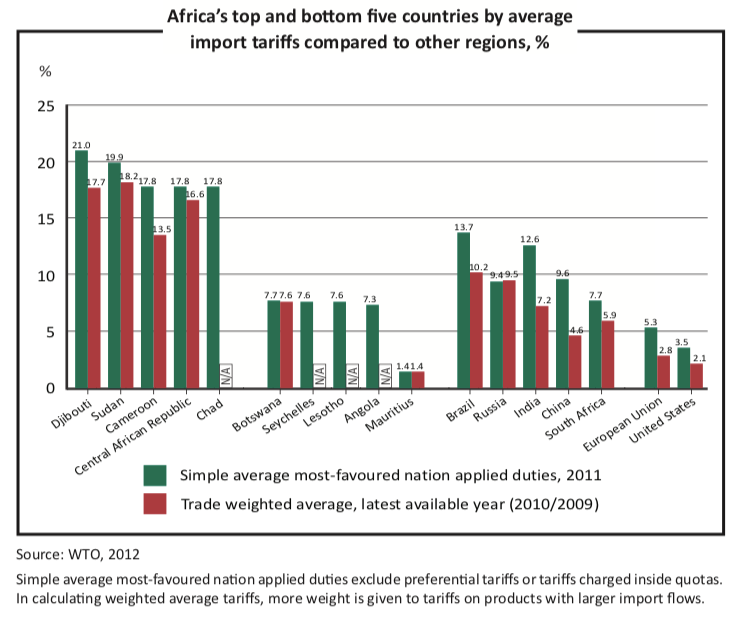

Meanwhile, import tariffs among developing nations, or between rich and poor countries, often remain much higher than those between developed countries. This means that a disproportionate share of the tariff burden falls on consumers and importing manufacturers in the poor world, even as South-South trade grows.

It is almost impossible to attach a specific number to it, but developing country tariffs are typically much higher than those in developed economies. As a result, some economists have estimated that by dismantling trade barriers unilaterally, most of the benefit of trade liberalisation could be obtained from the growing volume of trade between developing countries.

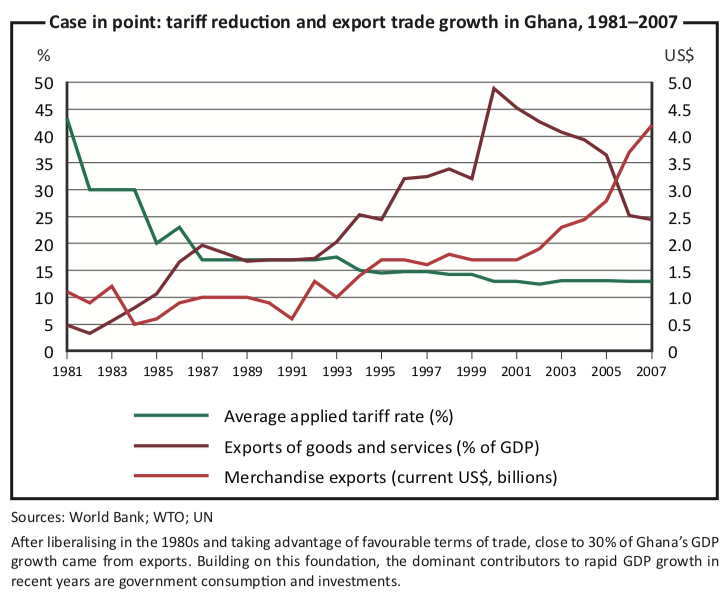

For example, the “Cairns group” is a coterie of mostly developing countries at the Doha negotiations that do not subsidise their agricultural exports. It cites a World Bank study which looked at developing countries that sizeably increased their ratio of trade to GDP and significantly reduced their import tariffs: they grew more than three- and-a-half times faster than those developing economies that did not.

One of the reasons for the failure of major global trade negotiations is that they do not lead to free trade agreements. They consist of tens of thousands of pages of regulations and reciprocal tariff agreements. A true free trade agreement would fit on a postcard, as Robert P. Murphy, an economics teacher at Hillsdale College in Michigan in the US, once pointed out.

In reality, the complexities of trade treaties mean that they often fail, and even when they do not, under-resourced countries—typically developing ones—are at a disadvantage.

In light of the obvious failures of global trade negotiations, which remain stubbornly deadlocked and incomprehensibly complex, perhaps it is time for African nations to take a different tack: begin acting unilaterally, either as South-South trading blocs, or as individual countries; and dismantle subsidies, tariffs and customs regulations that pose barriers to international trade.

First-movers will be able to take the moral high ground the next time they meet European, Japanese or American trade ministers to demand an end to the unconscionable protection of rich-world farmers and factory owners. But much more importantly, a great deal of the potential gain from trade liberalisation does not depend on the agreement of the rich world. For developing countries to help each other develop is, indisputably, a worthy policy.