Somalians in the United States

The Somali diaspora is a blessing and a curse for the government back home

Hail a taxi in Minneapolis, Minnesota, and you are likely to find a Somali refugee behind the wheel.

The twin cities of Minneapolis and St Paul are one of the largest Somali municipalities outside of Somalia. About 32,000 citizens of Somali origin are living in Minnesota, a state in the American Midwest, according to 2011 figures from the US Census Bureau. Community leaders suggest there may be as many as 50,000.

The Somali diaspora is a potent political force, driving local politics in Minnesota and in Somalia.

Abdi Warsame was elected to the Minneapolis City Council in November 2013, making him the top Somali-American elected official in the United States. Like Mr Warsame, many Somali-Americans are focused on their new lives, building a future outside the Horn of Africa. “Many of us left fighting in Somalia,” explained Jamal Abdulahi, a political activist, while looking at icy streets from a warm Minneapolis café. “Now we’re fighting for better snow removal.”

The Somali diaspora in Minnesota and around the world—is crucial to Somalia’s political future. Remittances boost Somalia’s struggling economy. Somali migrants educated abroad also occupy many top-level positions in Somalia’s government.

But the diaspora also destabilises Somalia. Sometimes, remittances end up in the wrong places. So do recruits. In October 2008, Shirwa Ahmed of Minneapolis became America’s first known suicide bomber, when he detonated a car bomb in northern Somalia. Since then, the FBI has publicly disclosed that at least 22 young men have left Minnesota to join the Shabab, a Somali Islamist militant group that orchestrated the Westgate shopping mall attack in Nairobi last September.

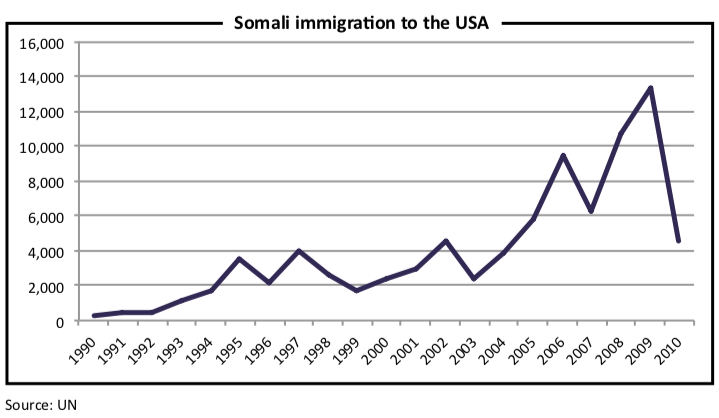

Somalia’s progress depends not only on creating good policies inside Somalia’s borders, but also on the assistance provided by its diaspora outside the Horn of Africa. Though thousands of miles away, they still feel connected to their homeland and the Somali government needs them to succeed. Somalia is one of the most dangerous places on Earth. It is a failed state, a victim of anarchy and chaos that have reigned since it descended into civil war in 1991, when clan-backed opposition groups toppled the existing regime but failed to re- build a coherent state in its place.

It is also one of the world’s poorest countries. Reliable economic data are scarce, but most estimates of per capita GDP range from $200 to $600, according to the UN, the Central Bank of Somalia and the CIA World Factbook.

Based on surveys conducted between 2007 and 2011, 85% of children never get the chance to attend primary school, according to the UN’s children’s agency. Life expectancy is a dismal 48 years for men and 52 for women, according to 2011 figures from the World Health Organisation. A true mid-life crisis in Somalia would strike in the mid-twenties.

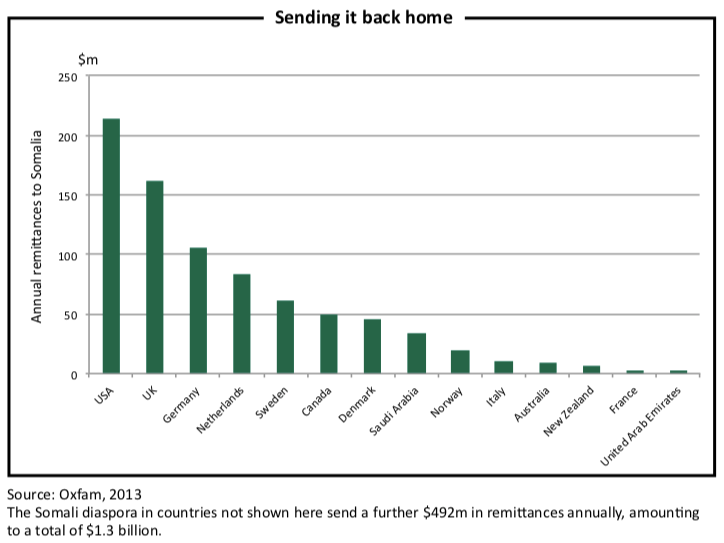

These numbers are alarming. But life would be even more horrifying if it were not for the generosity of Somali migrants living abroad. The Somali diaspora worldwide pumps an estimated $1.3 billion to $1.6 billion back into their homeland every year, representing about $165 for every citizen in Somalia, according to a 2013 Oxfam report. Since the average household in Somalia is home to six people, many households receive more than $1,000 a year, a fortune in a country where domestic GDP per capita is likely half that sum, or less.

The migrants’ contributions are impressive. Somali-Americans contribute $215m in annual remittances, meaning the average migrant sends $3,800 back to Somalia each year—affecting as many as 80% of Somali households, according to the Oxfam report. Most families use the remittances to buy the fundamentals: food and medicine, according to a 2013 report from the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation. If this pipeline of money dried up, Somalia’s already dire straits would worsen. Unfortunately, this pipeline is at risk.

Most Somali exiles send money home using Dahabshiil, a money transfer service with 130 branches in the country. Dahabshiil’s 5% commission is well below the 12% average for wiring money to Africa, according to the UN’s International Fund for Agricultural Development.

Money transfer services like Dahabshiil are a critical force for Somalia’s economic development and stability.

Some wired money, however, may end up funding terrorism or piracy. That concern is prominent in the United States, where the government has been on a post-September 11th quest to dry up terrorist funding. In pursuit of that goal, the US government shut down another prominent money transfer service, Al-Barakat. It was put on a list of organisations that support terrorism after rumours surfaced that it funnelled money to the 9/11 hijackers. Those rumours proved baseless. The US government removed Al-Barakat from its blacklist in 2012, but the business was no longer competitive.

More recently, Barclays Bank in the UK announced in 2013 that it was severing ties with Dahabshiil. The decision is pending: it has been met with fierce resistance from the government and human rights groups including Oxfam, 180 Somali civil society groups and several other international NGOs. They warn that cutting off the legitimate remittance pipeline will force financial transfers underground into unmonitored territory.

Barclays is likely afraid of compliance fines for failing to verify that recipients are not involved in illicit activity, a nearly impossible task for foreign banks wiring money to Somalia. (HSBC illustrates the inadvertent risk, as the US government fined it $1.9 billion in money laundering compliance fines in 2012 for transfers that involved Mexican and Colombian cartels.)

The trouble is sorting the legitimate transfers that help families and friends from those that fund terrorism and threaten to derail one of the world’s most fragile countries. Most illicit transfers are likely not detected, but some are.

In October 2011, two Somali women in Rochester, Minnesota were convicted in a Minneapolis federal court of sending nearly $9,000 that they had raised from the local community to the Shabab in Somalia. The women claimed they were raising funds for Somali charities. But the FBI taped conversations that suggested the women were aware of where the money was going and how it would be used. One woman received a jail sentence of 20 years; the other, ten years.

The diaspora not only sends money home but also provides fresh recruits for terrorism, and for politics. In addition to Minnesotans who have moved to Somalia to join the Shabab, many have returned to fight on the other side by helping to run the government. Several Minnesotans have become prominent politicians in Somalia, taking advantage of their American education as they try to help Somalia rise phoenix- like from its long-simmering ashes. A notable example is Ahmed Ismail Samatar, who grew up in Mogadishu, Somalia’s capital and has been teaching at Macalester College in St Paul, Minnesota since 1994. He returned to Somalia, ran for president in 2012 and lost. He has since returned to Minnesota.

Their expertise may be immensely useful, but there may be unforeseen downsides too. “The [Somali] cabinet usually has several people from Minnesota, but they always have the exit option—a comfortable house in Minneapolis or its suburbs that they can come back to if things fall apart,” Mr Abdulahi explains. “They might negotiate differently if they didn’t have that as a backup.”

Just as Somali migrants may be caught between two worlds, the old and the new, Somalia itself is caught between its reliance on the global diaspora—for crucial remittances and political guidance and the destabilising perils that come with such heavy dependence on foreign flows of money and people.

In early 2014, Somali migrants were again in the spotlight when Barkhad Abdi, a Somali-American cab driver turned actor from Minneapolis, was nominated for an Academy Award for his role as a Somali pirate in the Tom Hanks thriller “Captain Phillips”. Mr Abdi’s success in his new life—linked to portraying the perils and pitfalls of his home- land—is a parable for the Somali diaspora. Will those in the diaspora be like the real-life actor and use their success to help their friends and family back home? Or will Somali migrants mirror Mr Abdi’s fictional pirate counterpart and hijack Somalia’s recent political progress? The answer may lie more in Minneapolis than Mogadishu.