Growing entrepreneurs: not government’s business

Ambitious bureaucrats think they can replicate Silicon Valley, but history proves otherwise

Historians credit Frederick Terman, the former provost of Stanford University and dean of its engineering department, as one of the major founders of Silicon Valley in northern California. In the mid-1960s, a consortium of high-tech companies in the US state of New Jersey hired Mr Terman to replicate this hugely successful strip of innovation and entrepreneurship. The attempt failed.

The culture of cooperation that Mr Terman had established between the science and engineering departments at Stanford in California and the industries nearby simply did not happen in New Jersey. Companies wanted to keep their own research close to their chests. The only nearby university, Princeton, turned its nose up at applied, industry-oriented research.

Discouraged, Mr Terman moved to Dallas, Texas, where he tried again. He failed again. The story is told in an academic paper published in the 1996 winter issue of Business History Review, written by Stuart Leslie and Robert Kargon, Johns Hopkins University professors in the history of science and technology. After discussing the emergence of the Stanford-Silicon Valley effort, their study examines in detail other disappointing efforts, some of which enlisted the aid of Mr Terman and his protégés. Most flopped, too.

Last March, Scientific American ran yet another story on why it is so hard to replicate Silicon Valley. The magazine based its article on a 2012 study by Barry Jaruzelski, a partner at Booz & Company (which has since been renamed Strategy&), and Matthew Le Merle, of the same firm.

Silicon Valley succeeds because of the close cooperation between academia and industry, a rich venture capital ecosystem, a corporate culture that is particularly receptive to innovation and risk-taking, and high institutional tolerance of failure, according to their study. What distinguishes it from many international efforts to copy it, however, is its relative freedom from state interference. This makes any attempt by governments to replicate it oxymoronic. The very attempt will likely ensure its failure.

If even the godfather of Silicon Valley cannot duplicate this California marvel in a country that can throw the most money, skill and education in the world at the problem, what hope do politicians in Africa have?

Instead of actively trying to stimulate particular industries, the true role of government is non-interference. “That government is best which governs least,” wrote Henry David Thoreau in “Civil Disobedience”, the 1849 essay that was perhaps his most influential. “Government never of itself furthered any enterprise, but by the alacrity with which it got out of its way.”

According to Elizabeth Charnock, a technology entrepreneur and author writing

for Bloomberg in 2011, many countries have laws that inhibit entrepreneurship. “Whether it is taxation rules on stock options in Norway, the law in Germany that bars chief executive officers of companies that have gone bankrupt from ever making another attempt, or the giant amount of personal liability that founders have in most European countries, the potential upside is curbed and the downside almost draconian,” she wrote.

Politicians, like most business people, follow the herd. They wrongly think that they are visionary thought-leaders when, for example, preaching the virtues of “leap- frogging”, the ability of developing countries to adopt new technologies that remove the need for adopting older alternatives. History proves that they cannot foresee entrepreneurial successes, nor make them happen.

An example can be found in South Africa. Mobile technology can indeed be used to skip the need to bring wired telephony to every chicken shack in town. But the government’s policy never predicted this and enabled it unintentionally by getting out of the way.

When the first mobile licences were contemplated in the early 1990s, neither politicians nor prospective mobile operators themselves thought of the devices as anything other than toys for the wealthy. Government was happy to leave cell phones to the profit-seeking private sector, while keeping tight control over landline infrastructure. Contrary to everyone’s expectation, including that of the mobile operators, handset sales did not peak at a million or so rich people. They extended to every corner of society, and prepaid plans made cell phones affordable to almost everyone.

According to the International Telecommunication Union, there are 6.8 billion mobile subscriptions in the world and 89% of all people in developing nations have access to a mobile telephone. Fewer people have access to clean drinking water and sanitation, the most basic of government-provided services.

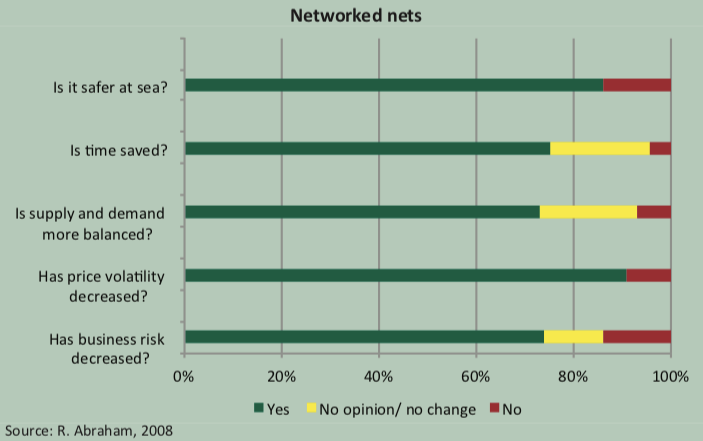

This technology penetration has led to direct improvements in people’s lives, without government intervention. One famous case study published in 2007 by the journal Information Technologies and International Development documented the use of mobile phones by 187 of the poorest people from the fishing industry in Kerala state, southern India (see chart on next page). Mobile phones enabled the industry to better match fishing boats to under-supplied markets, according to the paper written by Reuben Abraham, at the Indian School of Business in Hyderabad. Consumer prices declined, but more efficient transport and less wastage of highly perishable fresh fish led to lower costs, more stable prices and higher profits.

No politician would have said (or indeed did say) they were going to help make fishers more profitable by making prices go down. No bureaucrat could plan the innovation that made this happen. It all came from the people who had a specific domestic need and the entrepreneurs that supplied it. All the government did was get out of the way and permit it to happen.

Conversely, South Africa’s government liberally subsidised an effort to develop an electric vehicle called the Joule. The plan was not only to compete in the global market for such cars, but also to develop a lithium ion battery industry that would support it. The concept was sound; after all, battery technology is in dire need of a breakthrough. But it is not something that will happen just because government throws barrels of money at the problem. The product was late to market, uncompetitive, and failed. The putative battery factory never even got to the sod-turning ceremony.

Factors such as a healthy venture capital ecosystem with a high-risk appetite can stimulate entrepreneurship. An attractive environment for living and raising children is another. This is why the Silicon Cape initiative, a technology networking group in South Africa’s Western Cape province, founded by entrepreneurs Vinny Lingham and Justin Stanford, is showing some success: the region appeals to wealthy investors and aspiring entrepreneurs alike. But core to its success is that it is not government-led. No politician can afford to take a high degree of risk with enough public money to replicate Silicon Valley’s success. They would be hounded out of town after “wasting” money on failures like the Joule.

The view that entrepreneurship can be controlled, planned and stimulated is deeply mistaken. It wastes political energy and fiscal resources. Africa cannot afford grandiose plans by politicians to create the next Silicon Valley in every likely-looking hot spot. Just as in Silicon Valley, Africa can only rely on its people, their unique needs, the connections between them and private capital with a high-risk tolerance.

Entrepreneurship is not something that a smart bureaucrat with enough political will and deep pockets can create. Free people can, but only if bureaucrats get out of the way and stop punishing them for their business failures.