Genetically modified (GM) crops are safe for humans and animals to eat, research shows. They increase yields and lower production costs.

by Ivo Vegter

Felix M’mboyi, a Kenyan scientist, made world headlines late last year when he denounced the opponents of genetic modification in agricultural crops.

“The affluent west has the luxury of choice in the type of technology they use to grow food crops, yet their influence and sensitivities are denying many in the developing world access to such technologies, which could lead to a more plentiful supply of food,” Mr M’mboyi, executive director of the African Biotechnology Stakeholders Forum, an industry association based in Kenya, told the Guardiannewspaper. “This kind of hypocrisy and arrogance comes with the luxury of a full stomach.”

It is strong language, but the science seems to back him up. Africa needs to increase its food production by 40%, says the International Food Policy Research Institute. Nearly 3.5m children die of malnutrition every year, according to the World Health Organisation. Agricultural technology alone will not solve these problems. But it has an important role to play in what Calestous Juma, a professor in international development at Harvard and author of “The New Harvest: Agricultural Innovation in Africa”, calls the “toolbox” at the disposal of African farmers in the face of rising challenges.

Many anti-GM campaigners maintain that the technology will not benefit small- scale farmers in developing countries, but only enrich multinational agriculture services companies. However, recent research casts doubt on these claims. The International Service for the Acquisition of Agri-biotech Applications (ISAAA) released a report on February 7th 2012 that found that 90% of the 16.7m people who grew GM crops on 162m hectares worldwide in 2011 were small-scale farmers in developing countries with limited access to resources.

Some have questioned these figures because ISAAA is a New York-based non-governmental organisation that promotes GM crops. The free choice of farmers in China, for example, is questionable. In Brazil, most of the gains have been from large commercial farms. In India, while there appears to be a correlation between the adoption of GM crops and increased yields, closer analysis shows other factors may have been at least as important.

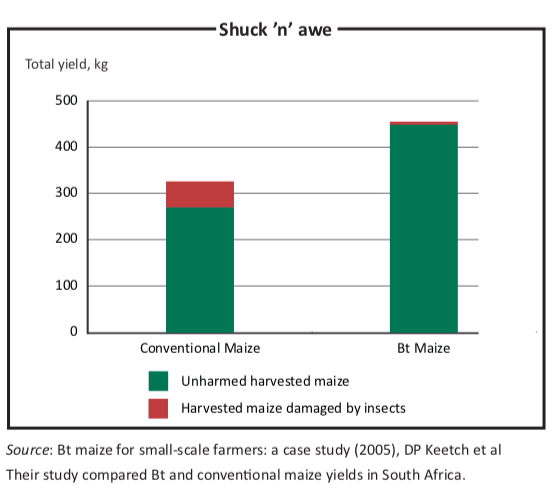

Writing in South Africa’s Farmer’s Weekly, Hans Lombard found that small- holder farmers call maize inoculated with the Bt gene iyasihluthisa, which means, “it fills our stomachs”. In 2010, some 20,000 hectares were planted with such maize and yields increased by 60%. One rural chief reported that yields increased from 1.5 tonnes a hectare to 4 tonnes a hectare, thanks to Bt maize, with significant savings on insecticide costs. Another reported extra income of R2,000 (about $230) per hectare for each of the 20 small-scale farmers in his district, thanks to higher maize production. A farmer in Soweto, near Johannesburg, told Lombard: “I paid R344 ($40) a hectare for Bt seed compared to R172 ($20) a hectare for conventional maize. My yield difference was 9,650kg a hectare compared to 7,200kg a hectare. My profit on the Bt maize was R13,166 ($1,500) [per hectare] compared to R9,908 ($1,125). With Bt maize I have financial benefits and enjoy a better quality of life.”

South African farmer Mark Coulson chose to switch to GM maize because it reduced spray applications by half, which cut production costs and implied less chemical exposure down the food chain. It also led to lower diesel and mechanical costs as well as less chemical exposure to the farmer and his workers. “Economically it made sense. Environmentally it also made sense,” he wrote in a letter. Why would farmers adopt a GM strategy if they thought it would result in their eventual impoverishment, the ruination of their land, or the ill health of their customers? And what would induce environmentalists in developing countries, far from the dusty soil of Africa, to denounce these choices?

Besides disputes about whether or not GM crops benefit small-scale farmers, as opposed to only large commercial operations, one factor might be the slow dripping of research studies that claim to have found damaging health effects in laboratory animals fed with GM foods. A recent example is a study conducted by French scientist Gilles-Eric Séralini, which made headlines thanks to horrifying photographs of rodents with large, presumably cancerous, tumours.

No sooner were the results released, however, than scientists, regulators, and even formerly sympathetic environmental journalists began tearing into the study. Mr Séralini and his colleagues were guilty of selectively presenting their data to exaggerate their findings, critics said.

Meanwhile, elsewhere in France, Agnés Ricroch, a lecturer in plant genetics at AgroParisTech and adjunct professor at Penn State University in the United States, performed a review of existing research that was funded by public money to eliminate bias introduced by private commercial interests. She and a team of toxicologists and biologists examined 24 studies on the long-term effects of GM food on a wide range of animals. None of the studies found any significant health impact in the animals under observation, according to their review published in the Food and Chemical Toxicology Journal.

Likewise, no credible studies have yet found significant risk to humans who consume GM food. For the most part, the chemical composition of these foods does not differ substantially from their non-GM counterparts, so the risks they pose are no different. Safety standards set by international agencies are based on content, rather than on the production process.

In a study published in the biotech journal Landes Bioscience, which is based in Austin, Texas, Graham Brookes and Peter Barfoot, consultants to the commercial agriculture industry, found that between 1996 and 2011, the combined impact of insect and herbicide resistance has resulted in an overall decrease of 17.6% in the use of these chemicals. If that sounds relatively small, consider that it saved 443m kg of these chemicals. Farmers save a great deal of money and avoid the unintended consequences of chemical use, such as health risks to consumers and farm workers, and reduce negative environmental outcomes.

In another paper, the two economists assessed GM crops’ economic impact on worldwide yields for the four primary GM crops: soybeans, maize, cotton and canola. They examined production costs, farm income and indirect farm-level income effects and found substantial net economic benefits at the farm level, worth $14 billion in 2010 alone.

Much of this economic benefit derives from genetic modifications that result in higher yields per hectare, increased drought resistance that makes marginal or degraded land more productive, and the reduced need for physical and mechanical labour to combat weeds.

The ISAAA report cited above finds similar economic benefits, of which 55% accrued to the developing world, and 45% to developed countries.

Besides improved farm productivity and lower environmental impact, GM crops also play a significant role in food fortification—the addition of desirable nutritional traits such as higher vitamin or protein levels to crops that otherwise lack them—and solving other health-related problems.

Africa is no stranger to fortified food. So-called “quality protein maize”, or QPM, a type of maize created by selective breeding to double its protein content, was introduced half a century ago. It is used to combat child malnutrition and HIV infection. The vast majority of this cultivar is today planted in Africa. A paper in the journal AgBioForum, by Carl Pray and others, described this hybrid as “both a technical and commercial success” despite the need for frequent seed repurchases. Another conventionally-bred hybrid, known as “orange-fleshed sweet potato”, or OFSP, increased yields and reduced childhood vitamin A deficiency in children by 24%, according to the paper.

But here, too, this technology has encountered opposition from environmental groups such as Greenpeace. That opposition is denounced by Patrick Moore, a founder of the organisation who controversially left it over its increasingly radical stance. He calls environmental opposition to GM food a “crime against humanity”.

Mr Moore’s argument is that beta-carotene-enriched rice, known as “Golden Rice”, is no different from cultivars produced by selective breeding. He told BiotechNow magazine: “Other GM rice varieties are able to eliminate micronutrient deficiency in the rice-eating countries, which afflicts hundreds of million people, and actually causes between a quarter and half a million children to go blind and die young each year because of vitamin A deficiency because there is no beta carotene in rice. We can put beta carotene in rice through genetic modification, but Greenpeace has blocked this.”

If Golden Rice succeeds, other nutrition-fortified staples will soon follow; most notably protein-enriched potatoes, cassava with many GM improvements including increased vitamins, iron, zinc, and protein, as well as agronomic traits, and a similarly- improved strain of sorghum.

However, the Pray paper warns that Mr Moore may be right about the op- position to GM foods jeopardising the success of food biofortification. Conversely, it says, the demand for fortified food has not led to the acceptance and success of GM technology.

GM is not a silver bullet. GM crops are bred to be resistant to herbicides, but weeds also develop herbicide resistance over time. As in conventional farming, herbicides and pesticides need to be rotated to reduce this threat. Public fear about GM food may also pose a policy challenge to African governments.

Some opponents of GM crops have charged that biotech seed companies aggressively pursue lawsuits for patent infringements against farmers whose crops were inadvertently cross-pollinated by plants from neighbouring farms. However, a federal court in Manhattan earlier this year dismissed a class-action lawsuit brought by some 300,000 farmers, represented by the Organic Seed Growers and Trade Association in the US, against Monsanto, a major GM seed vendor viewed as a “bully” by anti-GM activists. The court found that none of the plaintiffs had actually been sued or suffered any damages, and that the average of 13 lawsuits filed by Monsanto per year pales in comparison with the approximately 2m American farms.

Countries that seek to take advantage of GM farming would be wise to establish seed banks to conserve non-GM varieties. This would not only ensure genetic diversity for research purposes, but also provide insurance. Should future risks or the commercial behaviour of GM seed companies demand it, such seed banks would give farmers access to stock that is not burdened by patent claims. Such a policy can effectively counter fears that supposedly unsophisticated poor-world farmers are seduced into buying GM seed only to end up on a treadmill of purchasing GM seeds every season, losing the ability to return to ordinary multi-harvest seed.

Labelling policies based on voluntary disclosure and the prevention of fraud are relatively easy to administer. If farmers or retailers claim their food is free of GM ingredients, these claims must be testable and truthful. Conversely, mandatory labelling of GM food is complex, and imposes significant costs on GM food that artificially makes it less competitive.

Professor Juma is concerned that only four African countries—South Africa, Egypt, Burkina Faso, and this year, Kenya—have to date permitted imports of GM crops. The evidence is that Mr M’mboyi is right. The conservative views of international agencies and rich-world environmentalists are denying Africa access to technology that could improve its own food security, and is transforming agriculture elsewhere in the developing world.

[author] [author_image timthumb=’on’][/author_image] [author_info]Ivo Vegter is a South African columnist writing on economics, politics, law and the environment, and is the author of “Extreme Environment” a book on how environmental exaggeration harms emerging economies. In 2011, he was a finalist for the prestigious international Bastiat Prize for Journalism, which recognises work that promotes a free society. [/author_info] [/author]