The failure of a city’s water infrastructure will have anticipated consequences, but just as many will be unanticipated, turning the problem into more than the sum of its parts. Nowhere is this more evident than in the longstanding sewage crisis in Mogale City, encompassing Johannesburg’s West Rand towns of Krugersdorp, Magaliesburg, and Muldersdrift in South Africa’s Gauteng province.

More than a decade of underinvestment in Mogale City’s sewage infrastructure has come to a seemingly intractable head, and at this stage government crisis interventions look like the proverbial thumb in the dam wall.

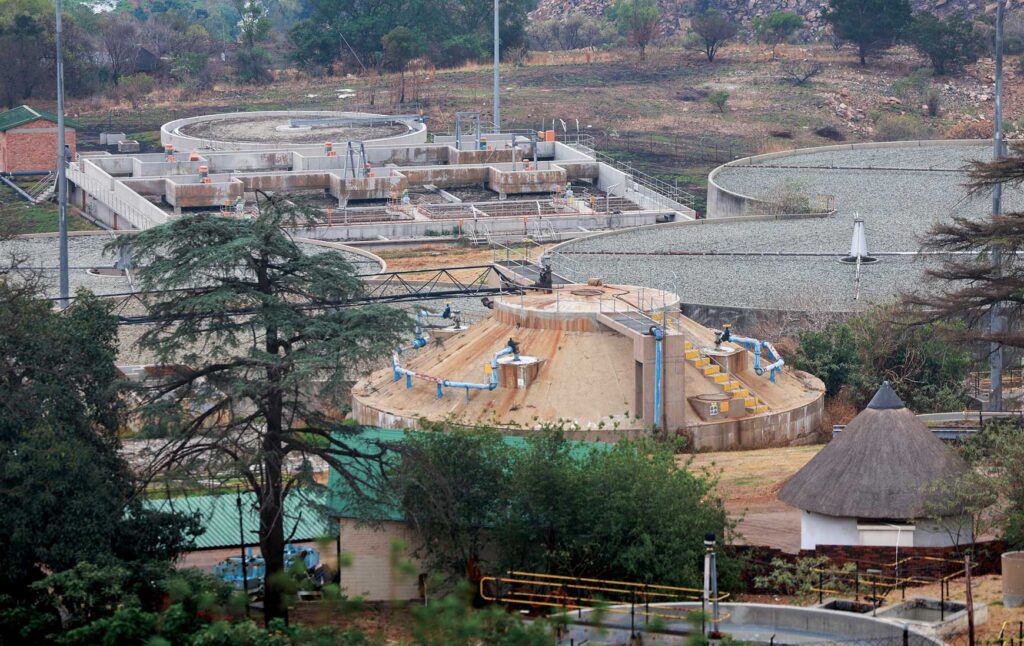

Not only are the city’s waterways continually polluted, due primarily to the breakdown of the once exemplary Percy Stewart and the Flip Human treatment plants, the UN World Heritage Site status of the Cradle of Humankind, which falls under Mogale City municipality, is also under threat.

By the end of 2024, despite R304 million the city received from the Department of Water and Sanitation over eight years, from 2016 to 2024, for water provision and related work and maintenance (including wastewater), more than half of Mogale City’s 22 sewer pump stations, and two-thirds of the water treatment plants, were broken.

As a result, raw sewage was being dumped into the Bloubankspruit, a tributary of the Crocodile River, which eventually ends up in the Hartbeespoort Dam, and the Rietspruit, a tributary of the Vaal River. Scientific tests conducted last September found the water in the Bloubankspruit contained almost 100 times more faecal content than the regulatory limit.

This raw, untreated waste in the river has killed aquatic life downstream, affecting businesses, farms, and the livelihoods that depend on them, while residents of the upstream townships of Kagiso and Munsieville have been living with hazardous wastewater spillages for years.

In March 2024, President Cyril Ramaphosa set up a task team under the leadership of Deputy President Paul Mashatile to resolve the issue of water pollution in Gauteng and other municipalities, including Mogale City, where, to start with, the dysfunctional Percy Stewart Wastewater Treatment Plant – which is critical to resolving the sewage issue – requires at least R150 million to fix. So, how did Mogale City get to this state of affairs?

Maintenance neglect, insufficient budget planning for wastewater infrastructure, and inadequate skilled personnel have been cited for years, including by President Ramaphosa in this year’s State of the Nation address. As the Green Drop Watch Report (2023) noted, “low levels of investment in infrastructure, and low capacity in respect of skilled personnel, are more likely to have wastewater systems in a critical state”.

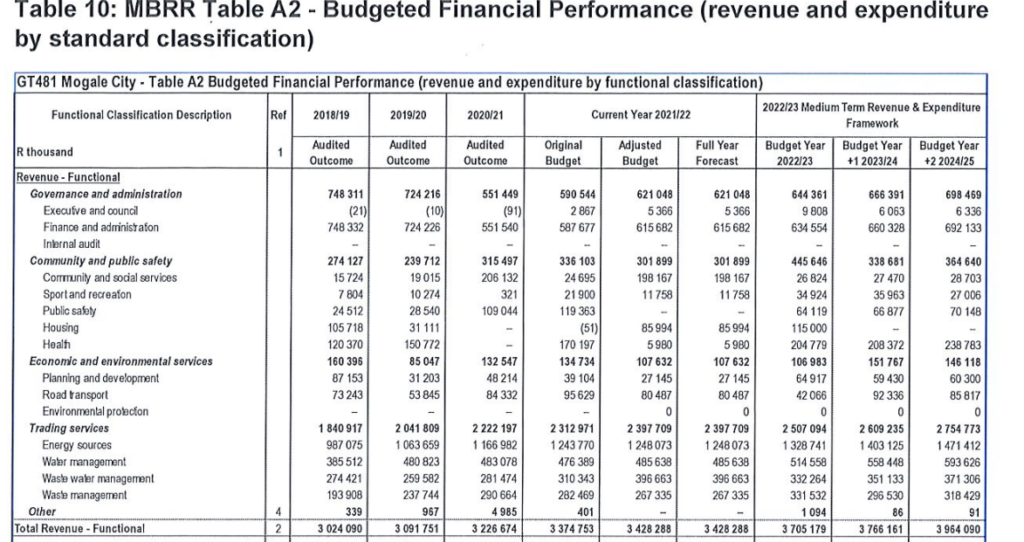

A look at Mogale City’s municipal budget for wastewater management over the past five years between 2019 and 2024 shows how under-prioritised sewage infrastructure has been; R274,421 was budgeted for wastewater management in 2019/20, increasing to R371,306 for 2024/25, for a population of 438,217 (2022 census) and an area of 1,342 km² (see graph below).

More galling, however, is Mogale City municipality’s channelling of taxpayers’ money to projects that serve councillors, not citizens. “It’s a case of Mogale City spending money on the wrong things, eg., R150 million on a new office building for the municipality,” said Dr Ferrial Adam, executive director of the lobbying group WaterCAN, an initiative for the Organisation Undoing Tax Abuse (OUTA), in a televised interview last September. “They could’ve spent that money on fixing the Percy Stewart wastewater facility for about R80 million. Only R8 million was spent on Percy Stewart (treatment plant) in the 2021/22 budget, and that was then reduced by 120%.

“It shows a complete lack of connection between the politicians and people on the ground. When we have municipalities misspending like this, it’s a disregard of basic human rights and their dignity.”

Mogale City municipality, which received widespread media attention at the end of last year over the sewage crisis, has now launched a phased refurbishment programme to restore the Percy Stewart treatment plant, rehabilitate other partially operational treatment plants, and repair all non-operational sewer pump stations.

“Of the national budget provision of R304 million over eight years, most of it went to providing bulk water infrastructure in informal or rural settlements,” Adrian Amod, Mogale City’s communication manager, told Africa in Fact. “Now, in the 2024/25 financial year, R22,5 million has been budgeted for Percy Stewart, with R15 million funded by the Integrated Urban Development Grant and R7.5 million from municipal funds.”

The refurbishments have started with a secure, durable boundary fence around the Percy Stewart plant, to prevent the theft and vandalism that has bedevilled it for years. (The fence was 60% complete by the time of going to press.) However, the R22.5 million is just an emergency budget; the refurbishment of Percy Stewart will cost R150 million in total and take at least a year to complete, according to Mogale City’s plans presented at a parliamentary oversight meeting last November.

Meanwhile, in his SONA speech, Ramaphosa said that national government would work with municipalities “to establish professionally managed, ring-fenced utilities for water and electricity services to ensure that there is adequate investment and maintenance” of these services.

But is this too little too late in the case of Mogale City?

Dr Anthony Turton, a scientist specialising in water resource management, doubts that the commitment and investment required to redress the situation in the long term is comprehensively understood.

“A sewage plant cannot store fluid, so what comes in has to be processed. Therefore, it is designed to have a specific retention time that is long enough for the various stages of the biological processes to be completed. The Percy Stewart treatment plant is the most hydraulically overloaded plant in the country, by about 250%. This means that retention time is halved. Consequently, it cannot be expected for such a plant to ever discharge safe effluent. It is biologically and chemically impossible. The only solution is to reduce the flow, which means building a new plant to take up the excess,” he told Africa in Fact.

Added to this is the problematic culture of patronage in ANC-run municipalities, which results in money meant for service provision continuing to be diverted “to keep patronage networks going”, said Turton. Mogale City reported in its in-year financial report tabled in November that it was R36 million in overdraft at the end of September 2024.

The council is unlikely to self-correct under the current circumstances, Turton said, adding that the negative consequences for the residents will be exponential. “The failure of infrastructure and services has serious implications for the local economy, for the value of land, for the future of revenues from rates being squeezed from falling land values.” Also, polluted wastewater leads to illnesses such hepatitis, cholera and diarrhoea, so the risk of a public health crisis remains present for as long as the sewage crisis continues.

The solution, according to Ferrial Adam, is far stricter national control of Mogale City. Not only should the Department of Water and Sanitation’s funding to the council be ringfenced, but a detailed audit should be produced, to ensure these funds were correctly channelled.

“If the Auditor-General finds that the funds have been spent incorrectly, then the money must be recouped from those accountable in their personal capacity. We will only see this kind of mismanagement of funds stopped when people are fired or put in jail,” she wrote on the WaterCAN site.

Yet, while offshoring accountability for municipal wastewater projects to national government might curtail wasteful expenditure in the short-term, municipalities need to shoulder this accountability themselves in the long run.

Good Governance Africa’s chief research officer, Dr Ross Harvey, says the sustainable remedy to poor performing municipalities is to “pilot substantive, systemic and sustainable interventions, empowering municipal management teams to build a governance register by which they can ensure basic attendance to the King IV Code of Good Governance.

“Like the Auditor-General, King IV is committed to moving entities beyond mere compliance, ensuring that governance mechanisms produce more robust performance. Building competence takes time, but it will surely stand as an antidote to the current malaise.”

Helen Grange is a seasoned journalist and editor, with a career spanning over 30 years writing and editing for newspapers and magazines in South Africa. Her work appears primarily on Independent Online (IOL), as well as The Citizen and Business Day newspapers, focussing on business trends, women’s empowerment, entrepreneurship and travel. Magazines she has written for include Noseweek, Acumen, Forbes Africa, Wits Business Journal and UJ Alumni magazine. Among NGOs she has written or edited for are Gender Links and INMED, a global humanitarian development organisation.