Once dismissed as an unlikely success story, this island nation has built a thriving, diverse economy on solid policies

In 1961, things were not looking good for the small Indian Ocean island of Mauritius. A British colony at the time, its economy relied almost entirely on sugarcane. Unemployment was rife and its multi-ethnic population was growing fast. So dire were its prospects that NobelLaureate for Economics, James Meade wrote: “It is going to be a great achievement if [the country] can find productive employment for its population without a serious reduction in the existing standard of living. The outlook for peaceful development is weak.”

Fast-forward 50 years and Meade’s prediction looks comically offthe- mark. As Joseph Stiglitz, another Nobel Prize-winning economist, wrote in 2011: “Mauritius…is neither particularly rich nor on its way to budgetary ruin. Nonetheless, it has spent the last decades successfully building a diverse economy, a democratic political system and a strong social safety net. Many countries, not least the US, could learn from its experience.”

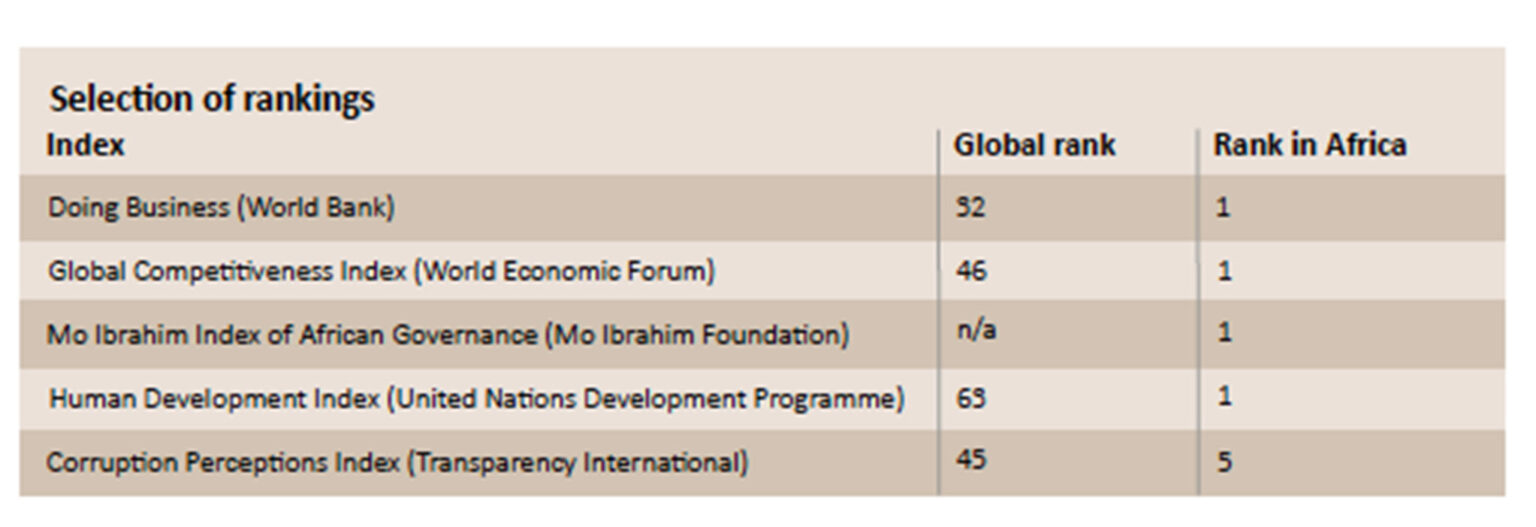

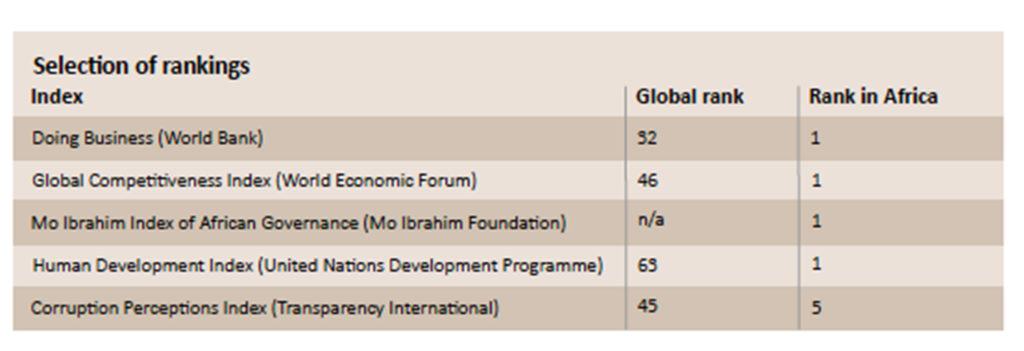

In the African context, the island country has become a beacon of good governance and best practice, topping many rankings within the continent, including successive versions of the World Bank’s “Doing Business” report, the World Economic Forum’s “Global Competitiveness” report and the Mo Ibrahim Index of African Governance. Often, it has even surpassed more developed countries (see table).

So how did this small mono-culture economy become the place to do business in Africa? The answer is deceptively simple: political commitment. Jean-Pierre Dalais, executive director of Ciel Group, one of Mauritius’s largest conglomerates active in textiles, financial services, agribusiness and more, says that following the 1970s and 1980s—which were marked by high unemployment, restrictive economic policies and punishing taxation—the country had no choice but to reform. “We needed to excel in corporate governance and doing business to attract people,” he says. “For our country to grow, we also needed to go outside, and for that we needed structures in Mauritius to have a business base.”

Mr Dalais says that the country’s experience in economic diversification in the 1990s—first through Export Processing Zones (EPZs), then tourism and the financial sector—was formative in fostering good relationships between the government and the business community. The collaboration is still thriving today. Santiago Croci Downes, senior private sector specialist with the World Bank’s Doing Business project, says that this shared interest is evident from the project’s records. “In the last eight years, we have recorded reforms almost every year and the level of activity has been really intense,” he says. Take “enforcing contracts”, for instance: Mauritius implemented reforms to improve this indicator in 2010, 2011, 2014 and 2015. “When they decide to reform, it’s not just a one-off: there is a middle- to longterm vision to improve the business environment,” he says.

Mr Dalais says that the country’s initial forays into diversification also provided valuable lessons into what makes a good business environment. “Gradually we understood that the only way forward was to be open and light,” he says. The result: the island’s economy is now one of the most liberalised in the world. It has a good, flexible Companies Act, and it is easy for companies to invest and divest, as well as to recruit and obtain permits, he explains. “We really have full movement of human capital and capital and that’s really important.”

On a business trip in Nigeria when interviewed by Africa in Fact, Mr Dalais had spent the previous hour in Lagos’s infamous traffic go-slow. The experience had given him an understanding of the challenges faced by the country, he said. Mauritius also has a simple but highly effective fiscal environment. Both corporate and income tax are 15%, and paying them is straightforward. This contrasts markedly with other countries where Ciel operates. “For instance, we have been challenged in Madagascar and Tanzania over how much tax we have paid,” he explains. “Very often these claims are frivolous and we spend a lot of time trying to prove that what we have paid is correct,” he says.

A key feature of Mauritius’s openness is the lack of travel restrictions. One business venture that benefits from this is the African Leadership University (ALU), a pan-African university that plans to open campuses in 25 African countries. Mauritius is its first venture with its first students enrolling in September 2015. The university is now building a campus, due for completion next year, to accommodate 1,000 students. Khurram Masood, ALU’s chief operating officer and head of college says that one reason the institution decided to open in Mauritius first is that it is the only country on the continent where 52 African nationalities can enter without visas. “We’re a pan-African institution. I have staff from 30 countries and students from 26 countries. I need this,” he says.

The university registered as an institution in Mauritius to make good use of the country’s breezy bureaucracy. “It’s the easiest place on the continent to do it and that has a big impact,” says Mr Masood. Other factors that helped clinch the deal for Mauritius were the country’s good infrastructure, especially its internet service (the university has high requirements for bandwidth and reliability), and the Board of Investment—Mauritius’s one-stop-shop investment agency—which rolled out the facilitation red carpet to ALU and political stability. “If I am going to start a university of the future, I want to look at a base where the core fundamentals are secure,” says Mr Masood.

Mr Dalais adds that the legal environment is excellent, with full recourse all the way up to the Privy Council in London, which makes “investors feel secure”. The country has also signed double-taxation avoidance agreements with 38 countries, 14 of them in Africa. Mr Dalais says that these treaties are a plus, but not the real reason businesses come to Mauritius. “Otherwise it would just be a postbox,” he says.

Rather, he argues, it is because Mauritius has developed a “full suite of services to open significant headquarters in Mauritius and use them as a base to expand in Africa”—a strategy the government is keen to promote. Mauritius is bilingual French-English and therefore well-positioned to deal with the two largest language blocs on the continent. The one limiting factor for the time being is air connectivity: Air Mauritius recently opened two new routes to Mozambique and Tanzania, but many destinations remain at least one stopover away.

The country also faces ongoing challenges regarding skilled labour, notes the “Global Competitiveness Index”. Mauritius has invested heavily in free education, as well as free health care since the 1970s, but the quality of its tertiary education is still inadequate for the demanding labour market. The index also shows that innovation remains limited.

Mr Croci Downes says that Mauritius could improve its two worst-scoring indicators in the Doing Business ranking: “registering property”, which mostly has to do with the quality and extent of the land registry, and “trade barriers”, because fees and duties for imported goods are relatively high. Such reforms will be important if Mauritius is to retain its spot at the top of the Doing Business ranking, he says. “If the reform pace slows down, [the country’s] ranking will be affected, not because it is doing anything wrong but because other countries are doing more,” he says. “Africa is one of the most active regions in the world at the moment, although it is admittedly starting from a low base.” Rwanda for instance, which ranks 62nd in the ranking and 2nd in sub-Saharan Africa, was the continent’s top reformer in 2016.

ALU plans to build its next campus in Rwanda, with its first intake of “fly-in/fly-out” MBA students starting in September this year. Mr Masood says that Rwanda, like Mauritius, has a policy of reaching out to and welcoming new businesses, and that it also makes considerable efforts to facilitate their operational set-up.

The government aims to see Mauritius ranking among the top 15 most investment-and-business-friendly locations in the world over the next decade. Thus a descent into complacency would seem unlikely in the foreseeable future.