Angola: mining scars

Angola’s extractive sector generates bundles of cash, but at what cost to the country’s environment?

Angola is one of Africa’s most biologically diverse countries, boasting a long Atlantic coastline, dense equatorial forests, rivers thick with mangroves, vast desert expanses, rolling savannah grasslands and high-altitude rocky outcrops

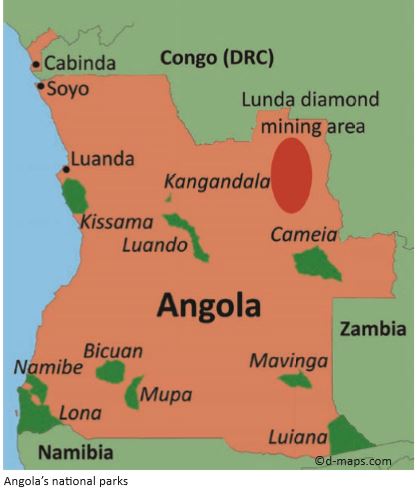

. It is also rich in natural resources. It is the continent’s second-largest producer of crude oil after Nigeria, the world’s fifth-largest producer of diamonds, and it is known to have substantial deposits of gold, copper, iron ore and other minerals. With a decade of peace now under Angola’s belt, the landmines largely cleared away and new roads and electricity lines being laid, national and international companies are queuing up to dig, drill and pump as much out of the earth as they possibly can.

Several dozen on-shore oil blocks are due to go up for auction in early 2014 to add to a ring of rigs and production facilities that cling to Angola’s coast, while allocations of new mineral concessions are being reported on a near-weekly basis.

It is clear that the government has embraced the expansion of its extractive sector, whose stellar revenues are driving strong post-war growth and have swelled GDP to the third-largest south of the Sahara, behind South Africa and Nigeria. But for all the in-flowing cash, poorly-monitored oil, gas and mining operations come at a high environmental cost and are leaving indelible scars on the landscape and local communities, government critics claim.

“At the moment most of Angola’s oil operations are offshore but even from far away the effects are clearly visible and the fishermen in Cabinda [an enclave of Angola separated from the mainland by a narrow strip belonging to the Democratic Republic of Congo] and Soyo [on the coast where the Congo River joins the Atlantic] tell us how their catches are shrinking due to pollution,” said Elias Isaac, Angolan country director for the Open Society Initiative for Southern Africa (OSISA), a campaign group founded by George Soros, a liberal financier.

“Now that onshore oil exploration has begun and more is planned, I fear we are only going to start seeing more and greater negative impacts on communities and natural habitats,” Mr Isaac said. Angolan civil activist Sergio Calundungo shares some of these concerns. Mr Calundungo is the former director of civil society body Action for Rural and Environmental Development (known by its Portuguese initials ADRA). He spoke to Africa in Fact in his personal capacity.

“The problem is that our government is more interested in profit from extractives than the environmental impacts the industries may have. Priority is given to the revenues rather than the methods of extraction,” he said. “Here in Angola people who are in government are very connected to the people who are in business and even though we have laws, they are allowed to be broken,” he added.

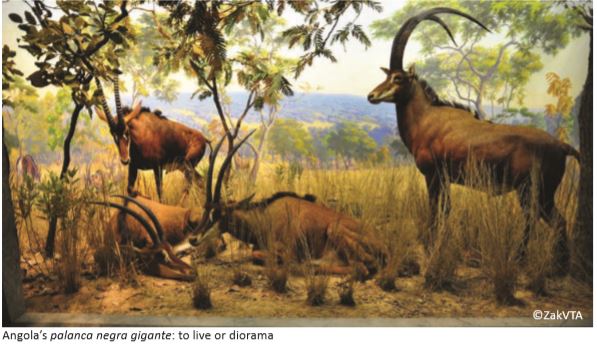

One such example of a broken environmental law emerged in May 2013 when an Angolan mining company was given prospecting rights inside the last wild habitat of the nearly extinct giant sable antelope, the Luando Reserve, south-east of Luanda, the capital. Known in Portuguese as palanca negra gigante, the animal is found only in Angola and it is the country’s national symbol. But its numbers have plummeted after decades of war and poaching.

From the thousands that existed in 1975, fewer than 100 giant sable antelopes are left, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN)

. The species is on the IUCN Red List of threatened species as “critically endangered”, one position before it is considered vanished and deemed “extinct in the wild”. That a mining company was given the green light to operate inside what is not only a protected reserve, where economic activity is forbidden by law, but also the natural home of such a rare and important species, sparked an outcry.

After some deliberation between the ministries of environment and geology and mines, and Endiama, the state-owned diamond company that has an equity stake in the project, it was announced in October 2013 that the “limits” of the concession would be redrawn outside the Luando Reserve. Questions remain, however, about how the venture was green-lighted in the first place.

“Every single project in Angola, whether it’s construction or mining or whatever, must submit an environmental impact assessment to the ministry and only if this report is certified can the company in question receive its licence,” said an environment ministry spokesman, who asked not to be named.

He admitted that he did not know how this project, developed by a consortium of previously unknown Angolan firms in partnership with Endiama, had received the go-ahead, given that its documentation clearly showed that it would mine inside a restricted area.

“What is important is that nothing happened inside the Luando Reserve,” he said. “It did not move forward and the ministry has reiterated its full support to the preservation of the palanca negra.” Vladimir Russo, formerly national director at the environment ministry, is among those who raised red flags about the diamond project.

Mr Russo is now an independent consultant and executive director of the Kissama Foundation, an Angolan environmental NGO that has led major conservation projects, including the restocking of large game into parks.

“Legislation has been developed to support sustainable development in Angola and it is aimed at regulating development by anticipating the potential problems and proposing mitigation measures,” he told Africa in Fact. “The problem is that not all the projects and project proponents follow the environmental legislation.”

He acknowledged that ventures respecting conservation laws are “better than they were ten years ago” but added concerns that part of the Kwanza Basin oil blocks due to go up for auction in early 2014 fell inside the perimeters of the Kissama National Park, an hour’s drive south of the capital Luanda, home to most of Angola’s large game and associated tourism.

In Angola the default explanation for failings in any area, from financial management to environmental monitoring, is weak capacity and limited human resources. It is not an unreasonable defence, given that the country endured more than 27 years of civil war up until 2002 and has had to rebuild everything, including its education system, from scratch.

However, Mr Calundungo said that nearly 12 years since the end of the war, the government should stop making excuses and instead show stronger financial and political commitment to the environment.

“This government likes to blame weak capacity, but I think that is a result of a lack of political will,” he said. “If you really want something to happen, then you make it happen.

In Angola when you see that the environment gets less than 1% of the national budget, then you realise it is not a priority and is not likely to be any time soon.”

The government misses no opportunity to boast through state media about all the high-level conferences and workshops attended by Fatima Jardim, its environment minister, or the country’s membership and signing of various international protocols against climate change. This of course serves to contradict the allegation that it lacks commitment to the environment.

Brian Huntley, an internationally-respected South African conservationist, who has collaborated closely with the Angolan government to develop national park strategies, also believes it is not all bad news.

“There is considerable international support coming to Angola from donor agencies to assist in rehabilitation of the national parks, so I would say things were looking better than they have in terms of commitment to the environment and new legislation,” he said.

“Now it’s just a question of implementation. It is possible to balance extractive activity with conservation; it just requires sensible planning, definition of core areas, and well-managed, environmentally sensitive operations.”

OSISA has long called for more transparency in how Angola manages its extractive revenues. It is now lobbying for independent monitoring of the environmental impacts of the oil and mining sectors, and crucially the open publication of that data. “There is a lot of secrecy and the government does not like people to ask questions or evaluate,” Mr Isaac said.

“That suggests there is something to hide. If things are as good as the government says, and there is no pollution or damage, then let people come in, evaluate independently, publish the results, and then we can all celebrate together.”

Unlike in South Africa, where concerns about rhino poaching feature regularly in the mainstream media, environmental issues get little air time in Angola. Questions of poverty and human rights violations tend to dominate civil society debates, which in themselves are stifled by a repressive pro-government media and a regime that does not appreciate open criticism.

“The people who are most affected by the damage to the environment—those who live in the Lundas near the diamond mines, or the fishermen in Cabinda—these are people without a voice,” Mr Calundungo said.

“They are completely marginalised and disconnected from decision makers in urban centres, but also not really represented by opposition parties or civil society. “People are sleeping where the environment is concerned in Angola and this needs to change.

I believe if we do not start to take action now, the consequences could be very serious in the longer term, affecting bigger issues related to land and water supplies.”