Alpha Condé was elected president of Guinea two years ago; but this West African nation does not have a parliament to check his power.

by Al Hassan Sillah

The discord in Guinean politics grows by the day in the absence of a national assembly. Blame both sides of the political divide: this government gridlock serves both their interests.

Alpha Condé was elected president in 2010 in Guinea’s first proper polls since independence from France in 1958. But his victory was controversial. None of the candidates won a 50% majority in the first round, but Cellou Dalein Diallo, a former prime minister, had a commanding 25-point lead. After he won the endorsement of the third-placed candidate, he seemed a shoo-in in the second round.

But accusations of electoral fraud and objections to election monitors delayed the second round by six months. Then, surprisingly, Mr Condé emerged victorious, narrowly defeating Mr Diallo, 52.5% to 47.5%. While Mr Diallo’s supporters claimed foul play, international monitors declared the elections to be fair. Eventually Mr Diallo accepted the results, urged his supporters to do the same and organised a united opposition front, composed of two groups of political parties, Le Collectif and the Alliance for Democracy (ADP).

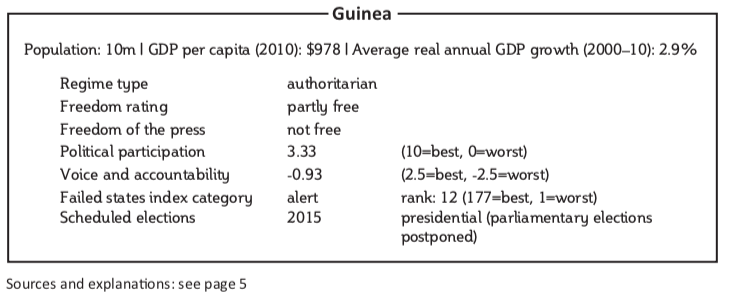

Legislative elections should have been held in May 2011, six months after the November 2010 presidential elections, but both Mr Condé’s government and the opposition have stalled these polls. This logjam has had dire consequences for Guinea: many international donors and financial institutions have withheld assistance. The European Union, in particular, has delayed transfer of more than $180m in aid for roads and urban development projects until the National Assembly is formed.

Guinea, the world’s largest exporter of bauxite, cannot afford an inert government. Poverty is rife among Guinea’s 10m citizens. Real GDP per capita was a mere $978 in 2010. While the rest of West Africa is experiencing a boom with average annual growth of over 5%, Guinea’s growth from 2000 to 2010 was just 2.9%. Many Guineans live without electricity and running water. The price of food has skyrocketed. Foreign Policy magazine’s 2012 failed states index rates Guinea 12th worst out of 177 countries. Worse, foreign investors are shying away from Guinea, citing diminished rule of law. Brazilian mining company Vale announced on October 26th 2012 that it was suspending development on an iron ore project worth over $2 billion.

The government hailed the cancellation of $2.1 billion of the country’s $3.4 billion debt by the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund in September 2012 as a major economic success. But critics viewed it as a non-starter. Although these debts were cancelled to allow the government to redeploy funds into developmental projects, the real impact would be negligible, said economist Juma Balde to Africa in Fact. “Corruption is still rife in the country’s administration and it was this same corruption and mismanagement of the state’s resources that led us to incur these debts in the first place,” Mr Balde emphasised.

The spectre of military rule still haunts Mr Condé. Before his election, a repressive military junta ruled. On September 28th 2009 the military opened fire on pro-democracy demonstrators, killing over 150 and injuring more than 1,000, many from gunshot and machete wounds.

In his latest reshuffle, in October, Mr Condé removed the last three military members from his cabinet, but a few remain in key state positions. His government has not answered calls by the families of the deceased protestors for the removal of Lieutenant-Colonel Moussa Tiegboro Camara, head of Guinea’s anti- drugs agency, who has been implicated in the 2009 atrocities.

The government and opposition clash at every turn about the frequently postponed legislative elections. Until just over a month ago, the two sides were at loggerheads over Lonceni Camara, then head of the National Independent Electoral Commission (CENI).

Mr Camara was alleged to hold a bias towards the ruling party because he shares the president’s ethnicity. While the government maintained it hadno powers over the commission, the opposition insisted on Mr Camara’s removal. The impasse deepened; violent public demonstrations and protest marches resulted in a handful of deaths. Mr Camara was forced to resign.

Following Mr Camara’s resignation, Mr Condé ordered the appointment of a new 25-person electoral commission to be composed of ten government members, ten opposition members, three members of civil society and two from the bureaucracy. When the government allocated one of the ten opposition seats to an opposition member outside of the ADP/Le Collectif alliance, the coalition decided to challenge this decision in Guinea’s Supreme Court. “We will never allow them [opposition outside of the alliance] to infiltrate our ranks,” raged the alliance’s fiery spokesman, Aboubacar Sylla.

The previous electoral commission contracted Waymark, a South Africa-based information technology company, to review the voters’ list. The opposition believes that Mr Condé’s government had too great a role in Waymark’s appointment and fear the company will favour the government. Last September, in a bid to demonstrate their objections, the opposition held another protest march. Security forces are said to have killed at least two people.

These disputes are assuming an ethnic dimension. Under Mr Condé’s govern- ment, public sector and parastatal appointments have favoured members of his Malinke ethnic group, who make up about 30% of Guinea’s population and are the military’s dominant ethnic group.

Mr Diallo’s political base is the country’s largest group, the Peul (known in English-speaking parts of West Africa as Fula or Fulani). Based largely in the country’s north, they account for about 40% of the population and have never produced a president. Mr Diallo claims that 13 of his supporters and kinsmen have been killed in demonstrations and local courts have imprisoned more than 100. “My people are being persecuted because of their ethnicity,” Mr Diallo alleged at a recent party meeting. In turn, President Condé’s supporters say Mr Diallo has hired thugs bent on making the country ungovernable.

Delaying legislative elections allows the opposition more time to organise polit- ically and reap the political rewards of an economy that is struggling under Mr Condé’s rule. Mr Condé’s government may take a step towards authoritarianism in response to perpetual opposition resistance, concentrating more power in the executive branch.

The strength of Guinea’s opposition parties cannot be faulted. They are organised and have won political battles: they succeeded in the removal of Lonceni Camara and the delaying of legislative elections for their convenience. It is the ethnic dimension of these battles that is ominous. If ethnic tensions were to escalate, it would foul the promise of a long-awaited democratic Guinea.