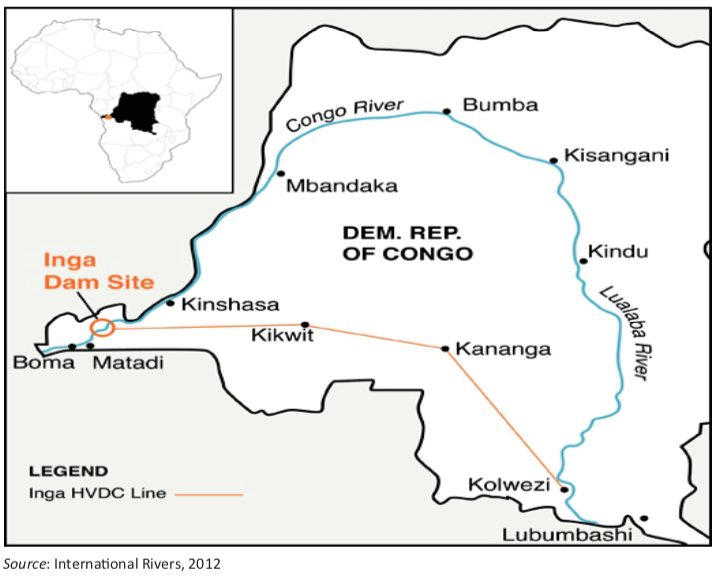

The Congo River is the world’s deepest. It is the second largest in terms of flow after the Amazon and Africa’s second longest after the Nile. On its banks in the western Democratic Republic of Congo, about 300km downriver from its capital, Kinshasa, is the site of the Grand Inga Dam project, the world’s largest proposed hydropower scheme. If built, this power complex could light up as many as 500m households, or about half the continent, according to the World Bank. Though two power stations, Inga I and Inga II, were built in 1972 and 1982 respectively, they have fallen into disrepair. Stephanie Wolters examines how years of government neglect and mismanagement have left the country’s energy potential dead in the water.

The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) is home to half of Africa’s forests, half of the continent’s water resources and its mineral reserves are worth a trillion dollars, according to the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). Despite this wealth, nearly two-thirds of its 66m people live on less than $1.25 a day, according to the World Bank. Most live without electricity and cook on wood fires.

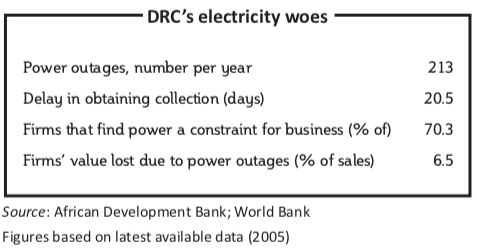

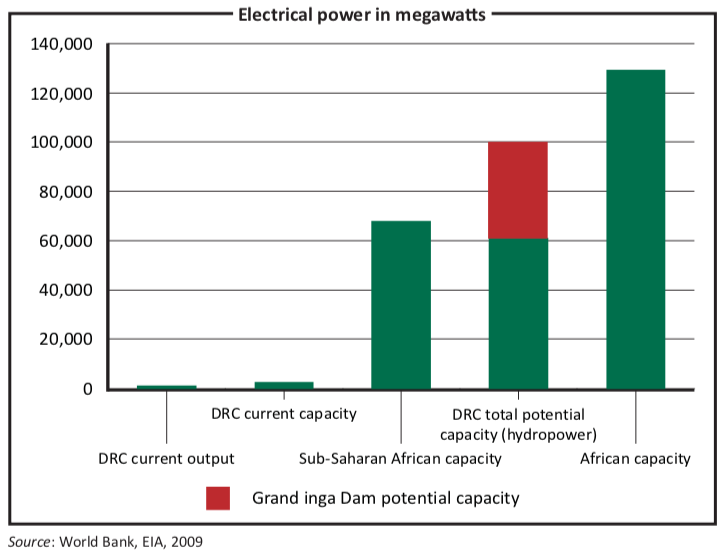

With its vast river networks, the DRC has Africa’s greatest hydropower potential, estimated at 100,000 megawatts (MW), yet only 9% of the population has access to electricity, compared to a sub-Saharan African average of 20% according to the World Bank. Most of those fortunate enough to be connected live in Kinshasa (40%) and the rest in other urban centres. Even then, they spend an average of ten days per month in the dark.

Currently, the country’s total installed electrical capacity is 2,400MW, but only 48% of that capacity is functional. The Inga I and II dams, the country’s largest hydroelectric installations, have an installed capacity to generate 1,775MW. But they are crumbling and currently generating only 800MW in total.

The Inga Dam project, located on the Congo river in Bas-Congo province in the western part of the country, was once the jewel in the crown of Zairian President Mobutu Sese Seko. Built during the era of the grands travaux (great works) in the 1970s and early 1980s, Inga I and II were linked through distribution networks to Kinshasa and to Katanga, where the electricity was used to increase mining output.

The construction of these two power stations cost close to $400m. It increased overall electricity capacity by 285%, but also burdened the state with heavy debt. For many years thereafter, the electricity bill paid by Gecamines, the state-owned copper and cobalt mining giant, accounted for most of the income earned by the national electricity company (SNEL). Over time, the Mobutu regime became increasingly corrupt and the looting of Gecamines’ coffers started to curtail production. As mining revenues declined, it gradually stopped paying its electricity bills to the SNEL.

One of the key reasons for the DRC’s declining electricity sector is “political interference in the management of SNEL, weak payment recovery and the decline in revenue, [which] have contributed significantly to the financial bankruptcy of the public operator”, according to the Congolese Ministry of Energy.

The World Bank, too, has cited concerns about governance and transparency in the sector following decades of corruption and conflict: “The conflict of the 1990s has considerably weakened SNEL’s capacity to function efficiently, leaving it with important challenges regarding governance of the enterprise, the physical resources, human resources, commercial operations and financial conditions. In addition, SNEL functions in a difficult political economy: the energy sector is a focal point of very powerful financial interests, while the governance and business capacity of this sector is very weak.”

Electricity shortages have crippled the copper and cobalt-mining sector in the DRC’s south-eastern Katanga province, the engine of Congolese economic growth. The World Bank estimates that the province endures 19 supply interruptions per month, with an overall energy deficit of 900MW. As a result, mining companies have developed their own local hydroelectric installations, but at a much higher cost: $0.10 per kilowatt hour (kWh), against SNEL’s $0.04 per kWh.

The majority of private businesses rely entirely, or at least partially, on their own more expensive generating capacity. SNEL has stopped issuing any new commercial contracts, further undermining economic growth and employment.

To boost the supply of electricity, the World Bank has taken the lead in the last few years in financing and managing the rehabilitation of Inga I and II, which should be completed in 2015, after a two-year delay.

New developments at Inga have been envisioned for some time. Here too, there have been setbacks. An initial agreement between the Congolese government and the electricity agencies of Namibia, Angola, Botswana and South Africa—known as Westcor—to develop phase three of the Inga project, with the construction of a new dam, was slow to find financing. It was eventually abandoned, in part, experts say, because the Congolese government was unable to make a firm commitment.

Australian mining giant BHP Billiton also expressed interest in developing the Inga III site as a source of energy for an aluminium smelter which it planned to build close to Inga. However, in February 2012, BHP announced that after a review of construction costs, it was abandoning plans for the aluminium smelter, and with it construction of Inga III. This was a major blow to the government, as BHP would have been a reliable customer and the dam would also have generated extra capacity for domestic consumption and exports to neighbouring countries.

The government has shrugged off the loss of the Inga III plant, but it knows that it needs to make progress on developing additional capacity. It must also start delivering on its promise to increase access to electricity, a cornerstone of its 2006 and 2011 political campaigns. According to the Congolese government’s official energy policy, it aims to provide 60% of the Congolese population with electricity by 2025.

President Joseph Kabila’s promises on that front were given a significant boost just a month before his 2011 re-election, when he and South African President Jacob Zuma signed a bilateral accord to jointly develop the Grand Inga dam, which would be by far the DRC’s most ambitious energy venture. It is projected to generate an estimated 44,000MW, according to the government and international financial institutions, more than China’s Three Gorges Dam on the Yangtze, currently the world’s largest hydroelectric facility. Expected to cost $50 billion, the Grand Inga would supply electricity to 500m people and several countries. It would also go a long way towards saving the DRC’s forests. The Congolese chop down 988,000 acres of forest every year just for heating and lighting needs, according to UNEP. The World Bank is also providing expertise and funds to reform SNEL, which will eventually be transformed into a private enterprise.

Last month SNEL launched a massive operation in Kinshasa aimed at recovering unpaid electricity bills, some of them going as far back as 2000. A SNEL expert told the World Bank that the DRC’s gross domestic product would rise by 3% if every customer were to pay their electric bill.

Not surprisingly, residents are resisting the operation, citing fraud, overbilling and general incompetence: “I bought my piece of land in 2006, but SNEL sent me bills going as far back as 2001, even though there was no electricity installed yet,” one customer told Radio Okapi. “The other problem is that even for what I paid, they tell me that the money is not in their account. I am not going to pay twice. I think this is some sort of swindle.”