Ethiopia’s footwear marches on

Bethlehem Alemu is making great strides in creating employment and developing artisanal skills

The flagship soleRebels store in downtown Addis Ababa, Ethiopia’s capital, is a hipster shoe haven. A lilting reggae soundtrack pervades the air. The wooden décor is splashed with Ethiopia’s warm national colours: green, red and yellow. Hundreds of funky shoe designs, their price tags ranging from $40 to $100, festoon the shelves.

In its midst sits Bethlehem Alemu, 34, the company’s founder and owner, sipping Ethiopian black coffee and boasting breathlessly about the fast rise of her foot- wear empire. “Our business model centres on eco-sensibility and community empower- ment,” she explains with self-confidence. “Our model maximises local development by creating a vibrant local supply chain while creating world-class footwear.”

Ms Bethlehem launched soleRebels with only five employees in 2005. She now employs more than 200 people who make shoes from Abyssinian hemp, organic cotton and recycled car tyres. These shoes, a combination of Ethiopian heritage crafts and modern design, are exported to 55 countries and sold in more than 65 stores. Ethiopia’s 20th century anti-colonial fighters, who wore sandals with rubber-tyre soles, inspired the shoes’ design and name.

Today, in addition to the flagship store in Ethiopia, 13 stand-alone soleRebels stores are selling shoes in five countries: Canada, Italy, Japan, Spain and Taiwan. Last year’s company sales reached $2m. Ms Bethlehem says she is expecting $5m in store sales this year as well as more than $6m in online sales over the next 18-36 months. Ms Bethlehem was born and raised in Addis Ababa, the daughter of a cook and an electrician. After gaining a degree in accounting from Unity University in 2001, she worked for three years in the apparel and leather sectors, gaining experience in production, design, marketing and sales. It was during these years, she says, that she developed a strong desire to focus her business skills on helping people from her community to escape poverty.

Footwear became her platform to harness the local artisanal workforce. With a $5,000 loan from her family, she opened a workshop in 2005 with five employees on her grandmother’s plot of land on the leafy edge of Addis Ababa.

For the first six years soleRebels produced shoes for large online fashion retailers such as Amazon, Endless, Whole Foods and Urban Outfitters. In 2011 Ms Bethlehem opened her first store in Addis Ababa. The next year, the company launched an outlet in Kaohsiung, Taiwan, followed by a shop in Vienna, Austria.

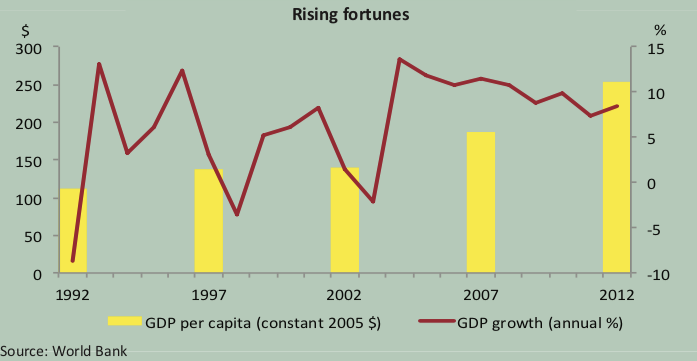

Ethiopia is today one of the fastest-growing economies in the world. Since 2004, its GDP has grown at an average of more than 10% a year, according to government figures. Conversely, its per capita income remains one of the world’s lowest and it is also one of the largest recipients of development aid, according to the OECD, an international think-tank.

Despite Ethiopia’s impressive economic growth, investors are grappling with a less impressive business environment. In the World Bank’s 2014 “Doing Business” survey, Ethiopia slipped one place to a lowly 125 out of 189 countries. In the bank’s “Ease of Starting a Business” index it fell four places to 166.

Graft, corruption, cronyism and a byzantine regulatory environment explain the country’s low ranking. Corruption permeates many of Ethiopia’s major institutions, with energy, tax, financial and transport sectors identified as having the highest levels of sleaze, according to a draft report released last January by the World Bank.

“Ethiopia suffers from high corruption risks because of the private sector’s dependence on the government,” says Ed Hobey, east Africa analyst for Africa Risk Consulting, a pan-African consultancy based in London and Nairobi. “Under Ethiopia’s state-led business and fiscal model, close contact with government officials is necessary for big businesses to operate successfully,” Mr Hobey explains. Local investors complain that the government continues to offer favourable treatment to certain ethnic groups. Ms Bethlehem is uncharacteristically silent when asked if the government was a help or a hindrance in starting and maintaining her business.

Ethiopia’s textile sector is the nation’s third-largest manufacturing industry after the food and beverage and leather industries, according to Bantihun Gessesse, spokes- man for the Ethiopian Textile Industry Development Institute. Over the last five years the government has offered many incentives to promote textile businesses, he adds.

“Ethiopia offers textile investors free factory rent, cheap electricity, duty free import of machinery and goods, favourable rules and regulations and cheap air freight,” Mr Bantihun says.

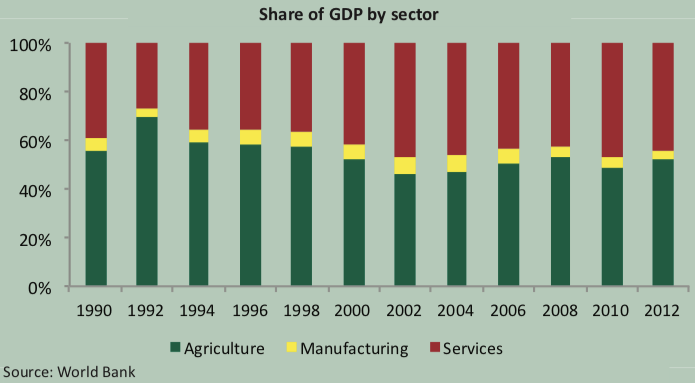

By adding value to raw materials and localising production, soleRebels is challenging the overwhelming propensity of African countries to export raw commodities that are manufactured into products overseas. This business ethos is in line with the Ethiopian government’s goal to transform the country to middle-income status by 2025 by boosting private investment, increasing trade and industrialising the agriculture-based economy.

As a successful retail chain from a developing country, soleRebels is an example of “how grassroots African companies can build successful global powerhouses literally from the ground up”, Ms Bethlehem boasts. For her efforts, CNN named her one of the “female entrepreneurs who changed the way we do business” in 2013 and Forbesmag- azine named her a woman to watch as part of its World’s 100 Most Powerful Women. The Schwab Foundation for Social Entrepreneurship named her as one of Africa’s five leading innovators at the 2012 World Economic Forum on Africa.