Southern Africa: world’s oldest customs union

The Southern African Customs Union has been less about easing trade than keeping failed states off South Africa’s doorstep

The rhetoric from Rob Davies, the South African minister for trade and industry, hit all the right notes, but could not hide his dissatisfaction.

The Southern African Customs Union (SACU) was moving beyond a treaty based on revenue sharing and common external tariffs, and “more firmly towards a deeper development and integration project”, he told South Africa’s parliament last July. However, he found it hard to downplay South Africa’s displeasure with SACU’s key feature, a revenue-sharing agreement that disproportionately benefits its smaller members at the cost of South Africa.

While South Africa, the region’s economic giant, accounts for 98% of the $6.5 billion in customs and excise duties levied at borders, about 55% of the proceeds are paid to its smaller members, which have become highly dependent on this revenue.

SACU is a free-trade area comprising South Africa and four of its immediate neighbours: Botswana, Lesotho, Namibia, and Swaziland, with a combined population of 58.7m. The junior SACU members are collectively referred to as the BLNS countries. All SACU members are also members of the Southern African Development Community (SADC), a regional economic grouping of 15 countries.

Regional economic areas such as SACU and SADC attempt to improve trade by creating larger markets. Inefficient and inadequate transportation, logistics and trade- related infrastructure and services can severely impede a country’s ability to compete, according to the World Bank. In particular, developing countries, and especially those that are landlocked like Botswana, Lesotho and Swaziland, face considerable challenges when it comes to easing trade.

One in five countries in the world is landlocked, according to a 2007 World Bank study. Among low-income countries, however, more than one in three are without a coast, while only three out of 35 high-income countries are blocked in. Most poor landlocked countries are in sub-Saharan Africa.

“Measures to actively facilitate trade are increasingly seen as essential to assist developing countries in expanding trade and benefiting from globalisation,” wrote Chris Milner, Oliver Morrissey and Evious Zgovu in a 2008 paper for the University of Nottingham in the UK.

The three economists emphasise that easing trade takes more than simply accelerating customs procedures. Benefits and lower costs can be gained by adopting broader policies, which incorporate transportation, distribution and communication.

They recommend: introducing automation and technology to speed up customs clearance; reducing excessive bureaucratic documentation; increasing transparency in import and export requirements; and improving cooperation between customs and other government agencies.

Poor infrastructure is not the only reason landlocked developing countries face high logistics costs, according to the World Bank. Governance issues and rent-seeking, such as bribes for overlooking bureaucratic rules, or charging commission for helping to meet them, are also to blame. Much of the facilitation is legal, but constitutes an unnecessary extra cost.

SACU has tried to ease border regulations, coordinate tariffs and trade policy, and strengthen trade negotiations between SACU member countries and the outside world. Nonetheless, “there is a lack of common industrial development [and] common policies and there is little intra-SACU trade,” said Reginald Selelo, a foreign direct investment specialist with the United States Agency for International Development, during a September 2011 meeting in Cape Town, South Africa.

The World Trade Organisation’s 2009 review of SACU’s trade policy, its latest, supports Mr Selelo’s claim. The report groups SACU member states under “other” in SACU countries’ import and export destinations. Their trade with each other represents less than 1% of their total trade with the rest of the world. Moreover, intra-SACU trade is very heavily biased in favour of South Africa.

SACU’s origins date back to the formation of the Union of South Africa in 1910, making it the oldest such agreement in the world. A renegotiation took place in 1969, some years after South Africa became an independent republic under the apartheid government.

This 1969 agreement devoted an outsized share of customs revenue to the junior members. It reflected the South African regime’s “need to buy friends and to as- sure [that the BLNS countries] did not become ‘little Hong Kongs’,” according to Roman Grynberg, a research fellow at the Botswana Institute for Development Policy Analysis. At the time, South African economic policy was protectionist and international economic isolation was growing. Its own customs and excise policies, as well as South Africa’s ability to act as a trade gateway to the region, would be undermined if small neighbouring countries acted independently as free-trade ports with lower customs tariffs.

After apartheid the SACU agreement was renegotiated again and the new terms came into force in 2002. Again, the BLNS countries’ revenue share was raised, recognising the smaller countries’ dependence on this income. It is widely viewed as economic development aid so that South Africa can continue to control regional trade tariffs and policies. According to Mr Davies, however, this imbalance reflects the SACU member states’ divergent views: South Africa treats tariffs as trade policy tools, while the BLNS countries consider them a major source of government revenue.

Nevertheless, South Africa remains dissatisfied because it loses $4.5 billion in revenue a year to its smaller neighbours, according to Mr Davies, while little progress at regional industrial development has been made. The 2008 global economic downturn sharply reduced the region’s customs revenue.

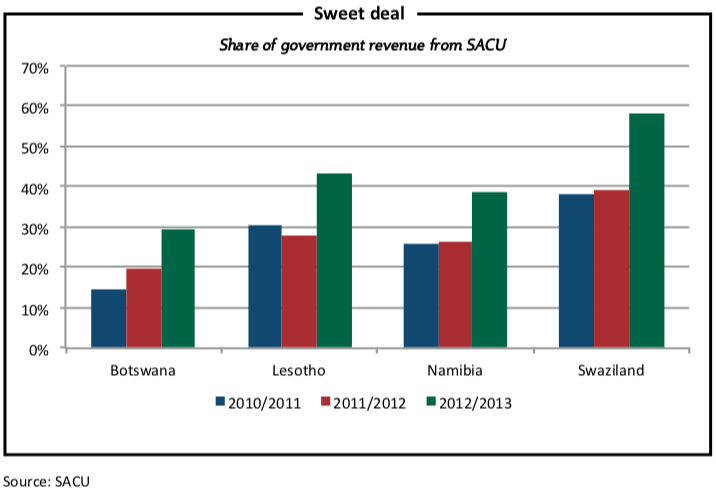

The smallest two members, Lesotho and Swaziland, depend on SACU for up to 70% of their [budget] revenue, according to Mr Grynberg. This unsustainable dependence on customs union income cannot conceivably be resolved without a radical new political arrangement, which would have to include free movement of people, goods and services across borders as part of an integrated common market, he added. Without this revenue, these countries could simply not sustain their budgets and would suffer economic collapse.

The financial crisis accentuated SACU’s flaws, wrote Peter Draper, head of the South African Institute of International Affairs’ trade programme, in a 2009 research paper. South Africa “cannot indefinitely subsidise” the BLNS countries under the SACU revenue-sharing mechanism, he wrote, while an “abrupt withdrawal” would “effectively create two failed states in Swaziland and Lesotho”. Already faced with Zimbabwe’s economic collapse on its doorstep, this would not be in South Africa’s interests.

Even Botswana and Namibia, which have more substantial economies, depend on SACU allocations for a third of their government revenue. An adjustment that would equitably allocate customs revenue by destination country would create a traumatic structural adjustment shock.

Their heavy reliance on SACU customs revenue has made the BLNS countries more eager to save the agreement, while South Africa has become more reluctant to continue funding these countries.

According to the South African Revenue Services, the 2012 trade deficit was 116.9 billion rand ($10.7 billion). Historically, South Africa’s trade statistics exclude BLNS trade. However, South Africa’s dominance in the bloc is such that were it included, the deficit would be reduced to 34.6 billion rand ($3.2 billion).

Attempts to ease trade among SACU members and create greater unity of purpose in negotiations with third parties continue to stumble over the revenue-sharing conundrum. Mr Davies is making a new revenue-sharing agreement a precondition for South Africa’s contribution to regional industrial and infrastructure development. “Without changes to the revenue-sharing agreement, work on cross-border industrial and infrastructure development lacks adequate financial support,” Mr Davies told South Africa’s parliament.

The disagreement between South Africa and its SACU partners over revenue- sharing is why economists such as Habiba Ben Barka are jaundiced about the promise of easing intra-African trade. “Today, regional economic groupings abound in Africa, with varying degrees of integration,” wrote the African Development Bank senior economist in a 2012 paper. “Nonetheless, they have failed to live up to their full potential in terms of achieving significant economies of scale, increased competitiveness, industrial modernisation and upgrading, higher domestic and foreign investment, and greater intra-regional trade. African countries have yet to fully exercise their bargaining power or to reap all the benefits of trading and engaging in a globalised world, where accelerated growth is posited as one of the key drivers of poverty reduction.”

Mr Davies insists that South Africa has good intentions in seeking to balance revenue sharing: to promote cross-border industrial and infrastructure development. Analysts such as Mr Selelo, however, believe that South Africa has only its own interests at heart. Revising the revenue-sharing agreement, he claims, will halt efforts to advance intra-SACU cooperation in developing infrastructure, regional industrial policy, common institutions, and unified trade negotiations with external third parties.

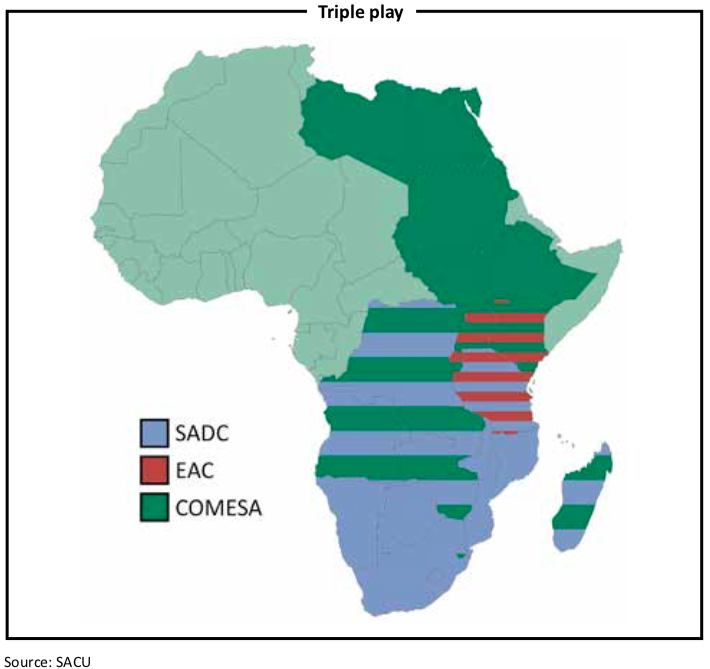

The consequences are not limited to retarding trade within the SACU, or even the larger Southern African Development Community (SADC). Analysts fear that it will impact on the formation of a much larger free-trade area, uniting the three major com- mon markets of sub-Saharan Africa, namely SADC, the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA) and the East African Community (EAC), comprising 27 countries with a combined nominal GDP of $1.16 trillion, according to the World Bank.

An agreement establishing this Tripartite Free Trade Area (TFTA) is expected to be con- cluded by mid-2014, said Richard Sezibera, chairperson of the task force negotiating this customs union.

SACU, the cornerstone of a future SADC common market, will in turn drive the TFTA. If internal disagreements can hamper industrial policy and regional integration on a small scale among only South Africa and four small neighbours, what hope is there for easing trade across the 27 countries and 600m people making up the sub-Saharan TFTA region?

Such a failure would sacrifice great benefits such as lower trade costs, higher government revenue, welfare improvements and economic growth, according to the University of Nottingham economists.

Mr Davies told parliament “lack of progress on the development of SACU insti- tutions is primarily a result of divergences in policy perspectives and priorities among members” of whether customs tariffs are to be considered primarily a trade policy tool or an income source.

A more cynical view might be that the lull is a result of South Africa begrudging SACU’s junior members $4.5 billion in customs revenue, while the smaller governments cannot survive without it. In either case, free trade in Africa will suffer.