To take, to tax, to share? These are the questions governments of countries rich in oil, gold, diamonds, platinum and other natural resources are asking themselves. How can they share this wealth with mining companies while making sure their citizens benefit, too? Richard Poplak examines the growing trend towards resource nationalisation.

No word in Africa’s post-liberation lexicon causes as much brouhaha as “nationalisation”. Along with its unhappy corollaries—state ownership, state participation, indigenisation—any talk of nationalising mines sends investors and neo- liberal wonks into a frenzy. The spectre of a dark era rises before us: corrupt Big Men swapping commodities for palaces until the national coffers are bare. But read the business papers in Africa and you will notice an increasing trend towards revisiting state ownership in the minerals and petroleum sectors. “Nationalisation,” a recent Goldman Sachs report warns us, “never works.”

Except when it does. Norway, Brazil, Botswana and Chile have successfully nationalised portions of their commodity sectors. The Norwegian government “partici- pates” in 50 to 70% of all mining licenses, collects taxes, royalties and dividends, and has built a petroleum fund worth $500 billion. What makes a state-by-state comparison so fascinating is that there is no standard model of nationalisation that can be applied like a salve. Models that work are the exception rather than the rule. In Botswana’s case, often cited as Africa’s leading light, the state has forged a partnership with the private sector. The Botswana government owns 50% of a joint venture with DeBeers, called Debswana, which mines the country’s richest diamond concessions, generating about two-thirds of gross domestic product (GDP) and more than 70% of export earnings.

What works for Botswana now may not work for Botswana in the future; nor is the model necessarily exportable. Despite efforts to bevel the edges off a massively complicated issue, “resource nationalisation” is not a single problem. There are sweeping differences between the various mineral and metal commodity sectors; Niger, for instance, does not have Botswana’s diamonds. Whichever way resource nationalisation is approached, it tends to expose an ideological conflict that dates back to the liberation era: privatised extraction in a liberalised economy vs. state-managed or state-owned extraction in a closed economy. This battle has long passed its expiry date.

African countries want more from their resources. But, as Dr Mzukisi Qobo, the former head of South Africa’s Department of Trade and Industry, wonders, “What are we talking about when we talk about more?”

Nowhere is this question being asked with more urgency than in South Africa. At the African National Congress (ANC) policy conference in June, something of a dry run for the leadership conference scheduled for December of this year, nationalisation was once again on the table. The ANC is less a traditional ruling party than an alliance of pre-liberation entities that squabble amongst themselves under the umbrella of a National Executive Committee (NEC). This push-pull between left and right, market- friendly and communist, is meant to keep the party in balance. Instead, it creates a political snake pit.

The debate has become so pointed that Mineral Resources Minister Susan Shabangu was forced to issue a palliative at Cape Town’s Mining Indaba 2012: “[In] this debate about nationalisation, we have consistently maintained that nationalisation is not the policy of the ANC or the government of South Africa.” This is not properly true: the ANC’s guiding document, the 1955 Freedom Charter, insists that “The national wealth of our country, the heritage of all South Africans, shall be restored to the people. The mineral wealth beneath the soil…shall be transferred to the ownership of the people as a whole.” Some interpret this as a call for nationalisation.

To nationalise or not to nationalise—therein lies the riddle repeated across the continent. In the early 1990s, following the end of the apartheid regime, Nelson Mandela was incapable of garnering support from the international community for nationalising South African mines. Privatisation became the order of the day, alienating the powerful National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) and other leftist alliance members. The nationalisation conversation never disappeared, because it was never properly pursued in the first place.

Stemming from an ANC National General Council resolution in 2010, the ruling party published a substantive study called State Intervention in the Minerals Sector (SIMS) designed to address the still festering wound. SIMS looks in detail at 12 countries’ varied approaches to resource nationalisation. It points out something that is true of most African countries: the minerals energy complex, or MEC, is “the main driver of the economy”. In 2011 the mining sector contributed $35.9 billion to the South African economy, or 9.8% of GDP, according to Statistics South Africa.

SIMS complicates the idea of resource nationalisation while studying its myriad formulations. How, for instance, does a state-owned enterprise (SOE) or a state minerals company (SMC) best inveigle itself into the mining sector? Is there any real difference between a super-profit tax and state ownership? Can a full-blown SMC mine and market commodities without private sector involvement?

South Africa’s sub-Saharan peers offer many, often contrasting, answers to these questions. In the Democratic Republic of Congo, Kinshasa demands 5% free equity and 15% to 51% negotiated equity shares in any mining venture handled through its SMCs Gecamines and Sokimo. They do not invest in prospecting and mine development, often leaving critical infrastructure, such as roads and hydro dams, up to the mining companies.

Compare this to Botswana, where the government is required to invest $1.5 billion in Jwaneng’s Cut 8 diamond mine, matching its partner DeBeers penny for penny. The DRC represents the old-school state-involvement model: sit around and wait for the cheques to clear. Botswana belongs to the new school: run state involvement like a business and reap the dividends.

As the executive director of the Free Market Foundation, Leon Louw, put it recently, “The Botswana government makes it very clear that it does not tax the mines, but just owns the shares in the partnership companies.” South Africa, despite legislation requiring 26% black ownership in local mining ventures, does not own the mines. It merely taxes them. According to Mr Louw, under its current tax policy, South Africa derives “50% of the substantial profits from South Africa’s mining industry” without investing a cent. Because the government does not participate in the industry, it does not subsidise the industry, as it must its parastatals.

Like most free marketeers, Louw would like this to continue. In West Africa, another nation has taken a very different approach.

Ghana has been at the forefront of the nationalisation debate since independence in 1957. Its gold production fell from 915,317 ounces in 1960 to 282,299 ounces in 1984, all but destroyed by poor state management and a plummet in global prices. In 1993, after radical liberalisation, production climbed tenfold to 2.9m ounces. Accra is determined to maintain this trajectory.

Ghana’s legislation is an example of a mixed approach that is becoming more and more common. Full nationalisation has not been on the table for 20 years: the state takes 10% free equity in both minerals and petroleum projects and has an option to buy a further 20% at market prices. Royalties float between 3% and 12% related to the operating margin, a policy designed to give companies a break should the international market dive.

The latest budget caused much handwringing in the mining industry, due no doubt to Ghana’s traditional bellwether status. It imposes a tax rate of 35% and an additional 20% profit, or “windfall” tax. There is also a capital gains tax that kicks in if a company increases in value after a merger. In a country where gold makes up 37% of exports, Ghana intends to extract as much value as possible from its resources.

The element of Ghana’s mining legislation that most rankles the industry is, of course, the windfall tax. For as long as the notion of windfall taxes has existed, it has acted as something of a doppelganger for the nationalisation issue. Calculated as a fixed percentage above the national lending rate, miners complain that supertaxes penalise them for profiting from the immense risks that are the hallmark of the business.

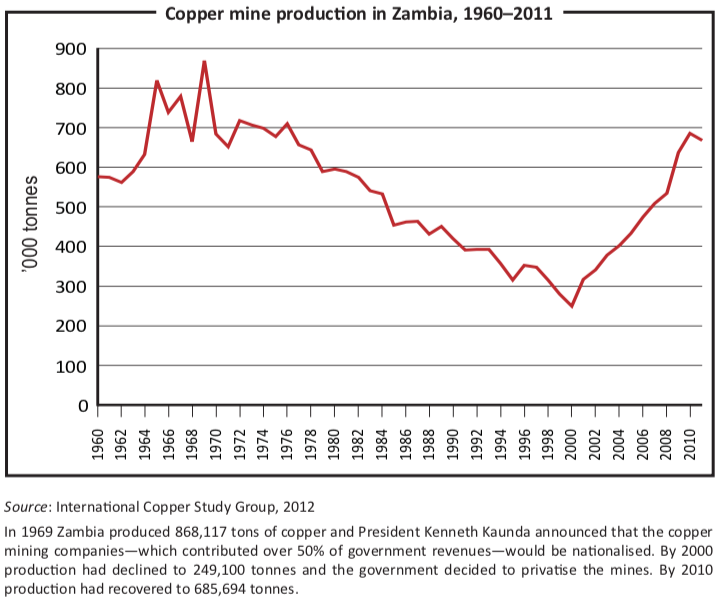

Several African countries agree. Zambia, under President Michael Sata, doubled royalties from 3% to 6% in the 2012 budget. But Zambia did not re-introduce the 25% windfall tax it abolished in 2009. In Lusaka, windfall taxes remain a botched experiment, on the scrap heap with independence leader Kenneth Kaunda’s nationalisation catastrophe.

At the recent ANC policy conference, a 50% super profit tax and a 50% capital gains tax were discussed in tandem with nationalisation. Indeed, they form part of the same argument.

While taxes and state ownership may increase government revenue in the short term, they do not necessarily increase development. The African Union Mining Vision demands a “knowledge-driven African mining sector that catalyses and contributes to the broad-based growth and development of, and is fully integrated into, an African market…” In African Union-speak, this is a call for a continent-wide commitment to beneficiation.

Beneficiation is the grafting of a macroeconomic vision onto mining policy. It is easier conceptualised than realised. The SIMS compilers commissioned a study by Sweden’s Raw Materials Group which looked at trends in state ownership in mines.

It found that when commodities prices are high, state ownership rises and the share of rents increases. In other words, governments behave like and compete with businesses. They enter sectors that promise rewards.

What is more, the global data on the success rate of SMCs shows that their efficacy is based on overall economic development. The Nigeria National Petroleum Corporation is notoriously dysfunctional; Norway’s Statoil reliably and routinely fulfils its mandate. For an SMC to work and for the state to become meaningfully involved in the minerals sector, SIMS suggests a roadmap: there needs to be a clear distinction between the state as owner and as regulator; clear lines of communication between the owner and the company; no link between the SMC and the treasury; full transparency; clear and transparent

development goals; and a listing of the SMC on the appropriate stock markets.

While neatly prescriptive, these criteria are still vague. They hint at the national- isation debate’s great and tragic handmaiden: beneficiation. Without development African countries will remain mere exporters of raw materials. When the resources are gone—and resources are always finite—there will literally be nothing left. In Indonesia, for example, miners must by 2014 process coal, iron and nickel into value- added products before export; the country is committed to jump-starting a culture of beneficiation that will spur development away from mere digging and drilling.

For Zimbabwe, which has been de-industrialising since the 1980s, such a policy would seem intuitive. Instead, the Mugabe regime demands a 51% share of all mining activity in the country, further scaring off already jittery investors. South Africa, which has the most to gain from an enlightened beneficiation policy, is similarly struggling with a model.

SIMS acknowledges that SMCs and nationalising chunks of the industry are not guarantees of success. Largely, it comes down to governance. To work, SMCs have to be linked to the macroeconomic picture and the state has to be mindful that investment in one sector does not drain other funding priorities, like housing or education. Considering the losses that other state-owned enterprises in South Africa have incurred, that would appear to be wishful thinking. And what of the conflict of interest that arises when the state is both a player and a regulator?

No matter which route governments choose, achieving a successful outcome requires mining industry participation. Blanket policy imposed from above rarely works. As SIMSputs it, any African country hoping for long-term success needs to create linkages throughout the MEC sector, train people and invest in mining technology. SIMS suggests a mining super-ministry to oversee the industry’s melding into the macroeconomic big picture, while increasing rents and creating a sovereign wealth fund, such as Norway’s.

Nowhere in SIMSis the dreaded “n” word tabled as a solution. Indeed, the trend in Africa towards nationalisation is something of a paper tiger. But more state involvement, higher taxes and greater pressure on mining companies to integrate with the wider economy are all likely to be part of Africa’s mining future.