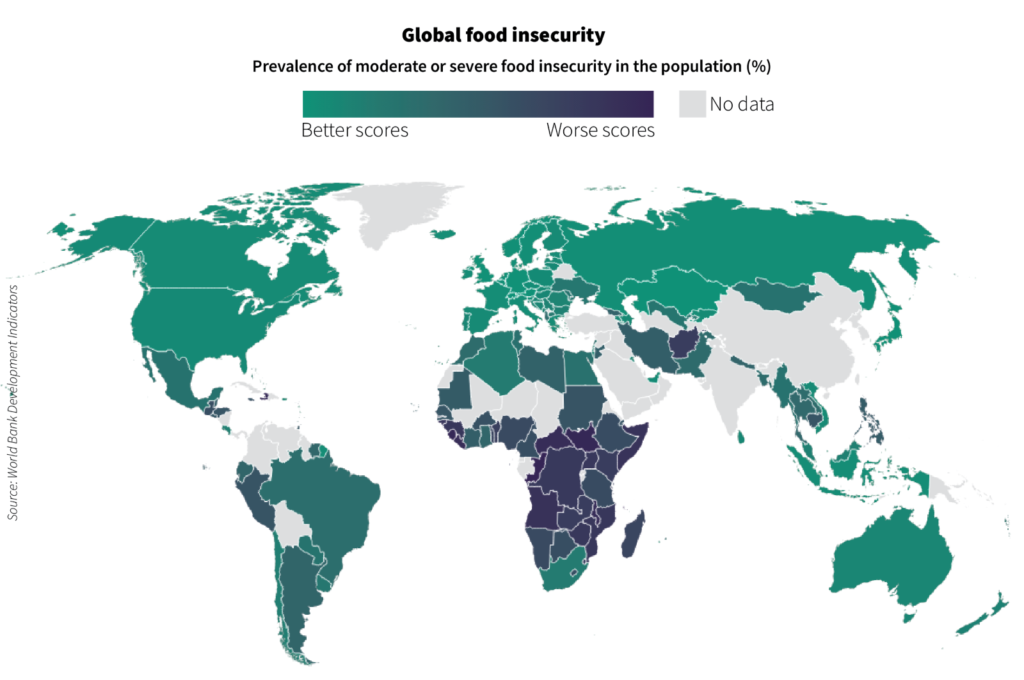

According to UNICEF’s State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World (SOFI) report this year, global hunger remained relatively unchanged between 2021 and 2022. It said that while progress was made in most sub-regions of Asia and Latin America, food insecurity levels are still well above both pre-pandemic levels and the SDG target of zero hunger by 2030. Critically, while most regions experienced either progress or stagnation, hunger continues to rise in all sub-regions of Africa.

In 2022, the global share of those affected by hunger in Africa was second only to Asia. Approximately 55% (402 million) of people affected by hunger in the world lived in Asia, while more than 38% (282 million) lived in Africa. In terms of variation across the continent, Algeria and South Africa report the lowest levels of food insecurity, with roughly 19% of their populations considered food insecure. Elsewhere, over 50% of populations in more than 30 countries on the continent are considered food insecure, with Sierra Leone (86.7%) and the Republic of Congo (88.7%) having the highest levels within the region.

According to UNICEF’s State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World (SOFI) report this year, global hunger remained relatively unchanged between 2021 and 2022. It said that while progress was made in most sub-regions of Asia and Latin America, food insecurity levels are still well above both pre-pandemic levels and the SDG target of zero hunger by 2030. Critically, while most regions experienced either progress or stagnation, hunger continues to rise in all sub-regions of Africa.

Also relevant is that food insecurity in Africa is not confined to rural or conflicted situations; the report highlights that in urban and peri-urban areas, the levels of moderate to severe food insecurity are on par with, and at times slightly exceed, those observed in rural regions. This heightens another concern, the “triple burden of malnutrition”, where many populations have a combination of stunting, increasing rates of obesity in urban areas, and a widespread problem with micronutrient deficiencies.

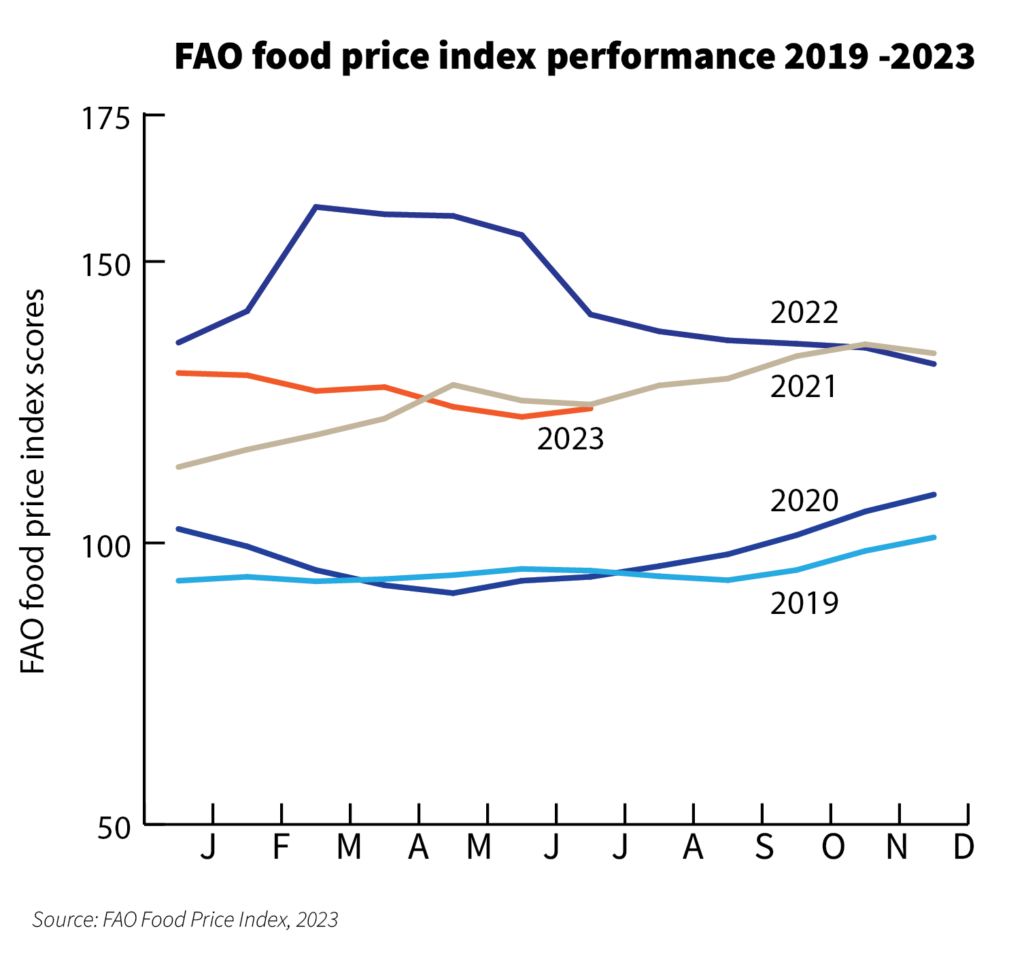

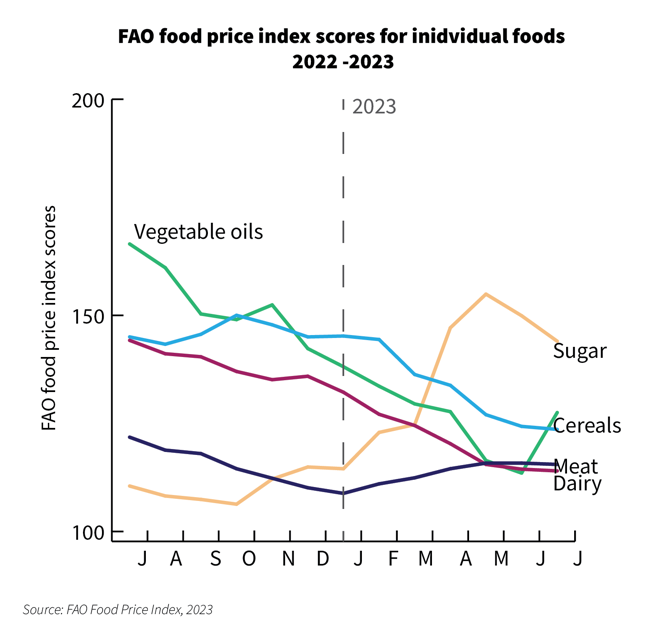

Underlying Africa’s sluggish progress towards food security has been a combination of market disruptions and increased political volatility, especially in the Sahel and East African regions. The lingering economic effects of the pandemic and ongoing global market inflation, along with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, have resulted in many countries placing restrictions on food exports to secure domestic supply. But this has still meant reduced access to key commodities for many countries on the continent.

These fluctuations have augmented the already elevated costs of food and fertilisers – a predicament prevalent even prior to the pandemic – and caused many staple food prices to drastically increase. According to the Brookings Institute, food prices in Africa increased on average by almost 25% between 2020 and 2022. In 2023 alone, more than 10 new food export restrictions were announced over only eight months, the latest being by Russia (a ban on the export of rice and rice groats) and India (a ban on the export of non-basmati white rice).

Within the continent, extreme climate variability and increased political instability across the Sahel and East Africa have severely compounded fractures in food and aid delivery systems. This is particularly true for the Horn of Africa, where the cumulative impact of these factors has been acutely felt. The region is currently facing its fifth consecutive season of drought—the longest drought in 40 years. Critically, the ongoing conflict in Sudan since April this year has displaced more than 2.2 million people and caused an acute humanitarian crisis, particularly in Darfur, where both the army and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) have been accused of restricting access to critically needed humanitarian aid.

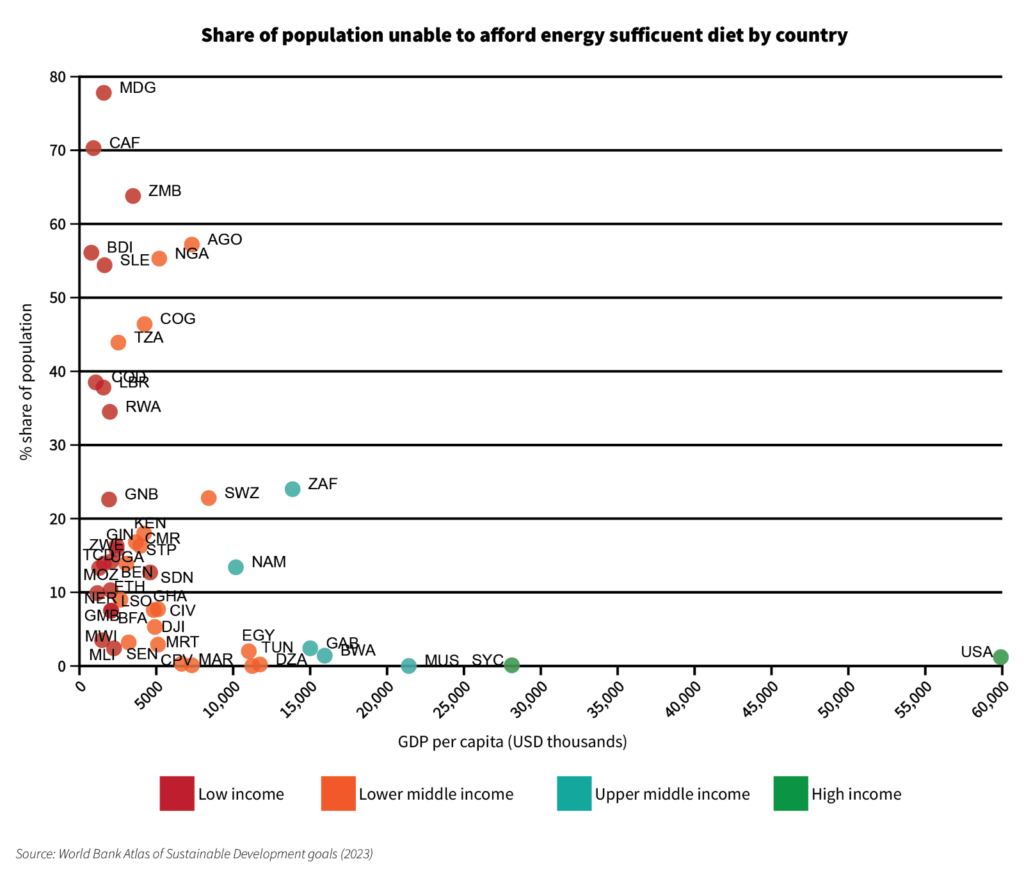

In tandem with these pressing issues, the broader challenge of food security encompasses economic dimensions, as underscored by recent data from the World Bank’s Food Prices for Nutrition database. According to this data, around 3.1 billion people, or 42% of the global population, could not afford a healthy diet in 2021. Of that, just under a billion (950 million) people, or a 30% share, live in sub-Saharan Africa.

The most basic diet to prevent hunger (the energy-sufficient diet) provides just enough energy for daily survival. The cost of this diet at a national level is calculated using the cheapest available starchy food, enough to sustain an adult woman requiring 2,330 calories a day. Globally, this type of diet costs $0.83 per day.

Considering the cost of living, an energy-sufficient diet is priced similarly in both the United States ($0.90) and Tanzania ($0.99). However, in Tanzania, despite the fact that the cost of an energy-sufficient diet is only slightly higher than the global cost, more than 44% of the population cannot afford this diet. In contrast, about 1% of the US population cannot afford the equivalent diet.

When looking at those who can afford a diet that meets the goal of preventing diet-related diseases and enables a healthy and active life, the affordability of a healthy diet looks even more bleak. Healthy diets are more expensive, but they embrace recommended dietary guidelines, achieve dietary balance, respect cultural preferences, safeguard long-term health, and mitigate all forms of malnutrition. In Tanzania, a healthy diet costs ($2.60) but is only affordable to a shocking 10% of the population, with the other 90% unable to access it. This is often the case for low- and lower-middle-income countries.

On the continent, the cheapest energy-sufficient diets are found in Malawi ($0.29) and Mozambique ($0.38), where 3,5% and 13.3% of their populations, respectively, could not afford this diet. The most expensive energy-sufficient diets are found in Nigeria ($1.38) and Angola ($1.40), with 55% and 57%, respectively—more than half the population unable to afford this diet.

In terms of healthy diets, the cheapest are found in Senegal ($2.19) and Tanzania ($0.99), with 53% and 88.7% of populations unable to access this diet, respectively. The most expensive healthy diets are found in South Africa ($4.1) and Angola ($4.33), with 24% and 57.2% of the population unable to access this diet, respectively.

In summary, the 2023 State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World report and Food Prices for Nutrition data present a sobering reality of hunger on the continent. Africa’s escalating food insecurity stands as a stark reminder of the challenges that persist despite regional advancements and that demand a transformation of the region’s food systems. The complex interplay of economic volatility, political instability, and climate vulnerability on the continent underscores the urgency for resolute and collaborative actions towards sustainable and resilient food systems that can ensure equitable access to hunger and nutrition security for all.

Mischka Moosa is a data journalist at GGA. She holds a Bachelor of Social Science with majors in Gender Studies and Political Science that she obtained from the University of Cape Town. Her focus of interest is on decolonial approaches to justice, development and transformation in Africa.