The Zimbabwean military’s reach

Brass defend political status quo to protect their own extensive business interests

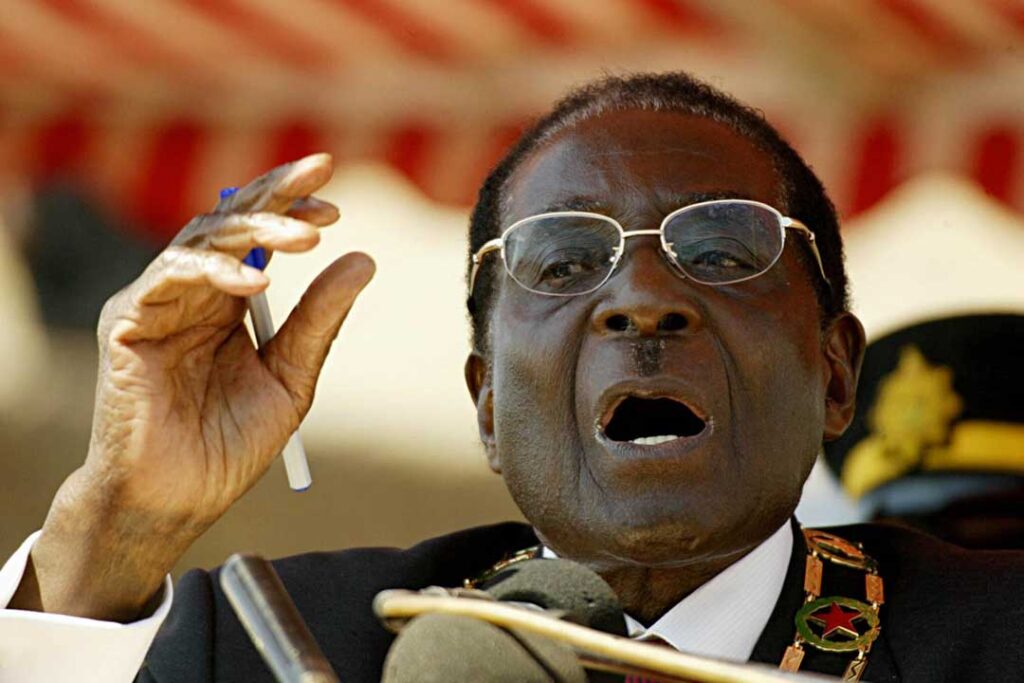

Two separate billion-dollar deals have turned the spotlight back on the unholy alliance between the ruling party, the military and big business in Zimbabwe. This network of mutual interests is curbing political change in the southern African country, opposition parties and civil groups say. During his visit to China last August, President Robert Mugabe oversaw the signing of a $2 billion deal with China Africa Sunlight Energy Company (CASECO), a joint venture between Harare-based Oldstone Investments and three Chinese firms to build a thermal power station in Gwayi, western Zimbabwe, by 2017, said Patrick Chinamasa, Zimbabwe’s finance minister. Martin Rushwaya, chairman of Oldstone Investments is also the permanent secretary in the country’s defence ministry. Another mega-deal was signed a month later, this time for a platinum mining project in Darwendale, 70km north-west of Harare.

The joint venture is between Zimbabwe’s Pen East Mining Company and a Russian consortium of three corporations, Rostec, VI Holdings and Vnesheconombank. Total investment in the project would rise to $4.8 billion, said Walter Chidhakwa, the country’s minister of mines, in September. Tshinga Dube, a retired colonel, wears many hats. In 2011 he was listed as Pen East’s board chairman. He is also chairman of diamond mining company Marange Resources and general manager of Harare-based Zimbabwe Defence Industries (ZDI), which manufactures and supplies army uniforms, equipment and ammunition. Mr Dube is not the only high-ranking military official—either retired or serving— to have multiple business interests in Zimbabwe. “There are certain elements within the military who are benefiting while the majority [of Zimbabweans] are suffering,” said Douglas Mwonzora, secretary-general of the Movement for Democratic Change-Tsvangirai (MDC-T), Zimbabwe’s largest opposition party.

“Those who benefit unduly then interfere with the politics of Zimbabwe in order to protect their wealth,” he said. The military’s close ties to the ruling Zanu-PF date back to the country’s liberation struggle. Almost all current senior officers participated in the war against the colonial regime, fighting for two armed wings that merged in 1987 under the Zimbabwe African National Union-Patriotic Front (Zanu-PF). The military has openly acknowledged its allegiance to the ruling party. Ahead of the 2002 presidential elections—in which Zanu-PF for the first time faced a real electoral threat from the MDC—General Vitalis Zvinavashe, then commander of the Zimbabwe Defence Forces, famously announced that his forces would not serve under MDC leader Morgan Tsvangirai if he won. “We will…not accept, let alone support or salute, anyone with a different agenda that threatens the very existence of our sovereignty, our country and our people,” General Zvinavashe said.

When Mr Mugabe lost the first round of the 2008 presidential election to Mr Tsvangirai, senior military officers intimidated villagers into voting for Zanu-PF in the runoff election, according to a 2008 report by Human Rights Watch, a New York-based lobby. Mr Tsvangirai ultimately pulled out of the second round. Mr Mugabe has consistently repaid military figures for their loyalty. He awarded most security sector bosses large farms in Zimbabwe’s controversial land reform programme in 2000. He has also routinely deployed top military officials to head parastatals and government ministries. These include, among many others, retired Air Commodore Mike Tichafa Karakadzai, who was general manager of the National Railways of Zimbabwe (NRZ), and retired Major-General Mike Nyambuya, a former minister of energy and current chairman of the controversial National Indigenisation and Economic Empowerment Board. Mr Mugabe defended these and similar appointments at Mr Karakadzai’s funeral in August 2013.

The practice would continue, Mr Mugabe said at the service, because those in the military were “role models of valour, patriotism, honesty, industriousness and discipline”. Zimbabwe’s diamond industry is another sphere where military involvement runs deep. When the Zimbabwe government took over the rights to the Marange diamond fields in eastern Zimbabwe in 2006, high-ranking officials in the security sector formed companies to exploit the gems. Two of the most prominent diamond mining companies are Mbada Diamonds and Anjin Investments. Robert Mhlanga, a retired air force vice-marshal, chairs Mbada Diamonds while Anjin’s company secretary is Charles Tarumbwa, a serving brigadier- general. During the unity government period between 2009 and 2012, Zimbabwe’s parliamentary committee on mines and energy led an investigation into the activities at the Marange fields.

According to its June 2013 report: “Secrecy and lack of transparency in the diamond mining industry has resulted in serious leakages and failure to remit satisfactory revenues to the state.” Finance minister during this period, Tendai Biti, then of the MDC, consistently complained that the treasury was not receiving revenue from diamond sales. In 2012 he slashed the country’s national budget after revenue from diamond sales was far below expectations. “While the minister of finance expected $600m from the proceeds of diamond exports in 2012, the state only received about $41m,” Mr Tsvangirai said in October 2013 during an Oxford University lecture. “This is against reported sales of diamonds running into billions of dollars every year.” In 2012 Global Witness, a UK-based watchdog, detailed the intricate network of Chinese and Zimbabwean security, police and intelligence services operating at the Marange diamond fields.

Its report reveals how Zimbabwe’s secret police, the Central Intelligence Organisation (CIO), apparently received financing from Sam Pa, a Hong Kong businessman. It also suggests that several CIO members are directors of Sino-Zimbabwe Development, a group of firms with mining interests registered in the British Virgin Islands, Singapore and Zimbabwe. “Together with factors such as the presence of the permanent secretary of the ministry of defence [Mr Rushwaya] on Anjin’s executive board, these company records have led Global Witness to conclude that half of [this] large diamond mining company is likely part-owned and part-controlled by the Zimbabwean ministry of defence, military and police,” the report states. The loss to public coffers is particularly regrettable considering the state of the country’s economy. A liquidity crunch has resulted in many companies either shutting or scaling down. More than 85% of the population is not formally employed, according to opposition party estimates.

Between 25% and 35% of the population are undernourished, according to 2014 World Food Programme figures. Military-business collaborations are not necessarily wrong, said Martin Rupiya, executive director of the African Public Policy and Research Institute, a Nairobi-based think-tank. These partnerships are common in Europe and the US. But in Zimbabwe’s case, he said, the absence of transparency and the unanswered corruption allegations raise questions. “The challenge in the case of Zimbabwe is that the [Zanu-PF] party actually does not have a clear policy,” Mr Rupiya said.

“What remains is the [internal] fight between factions—a factor clear to citizens—with an increasingly weak and ineffective president handing out contracts [to military personnel] to secure his own power base.” Until recently, Zanu-PF had two sparring factions, one led by Emmerson Mnangagwa, Zimbabwe’s justice minister, and the other by Joice Mujuru, the fomer vice-president who was sacked in December by Mr Mugabe. Mr Mnangagwa, who was defence minister from 2009 to 2013, remains close to the military. As this magazine was going to press, he was about to be sworn in as Zimbabwe’s new vice-president. He appears to be leading the race to succeed the 90-year-old Mr Mugabe.