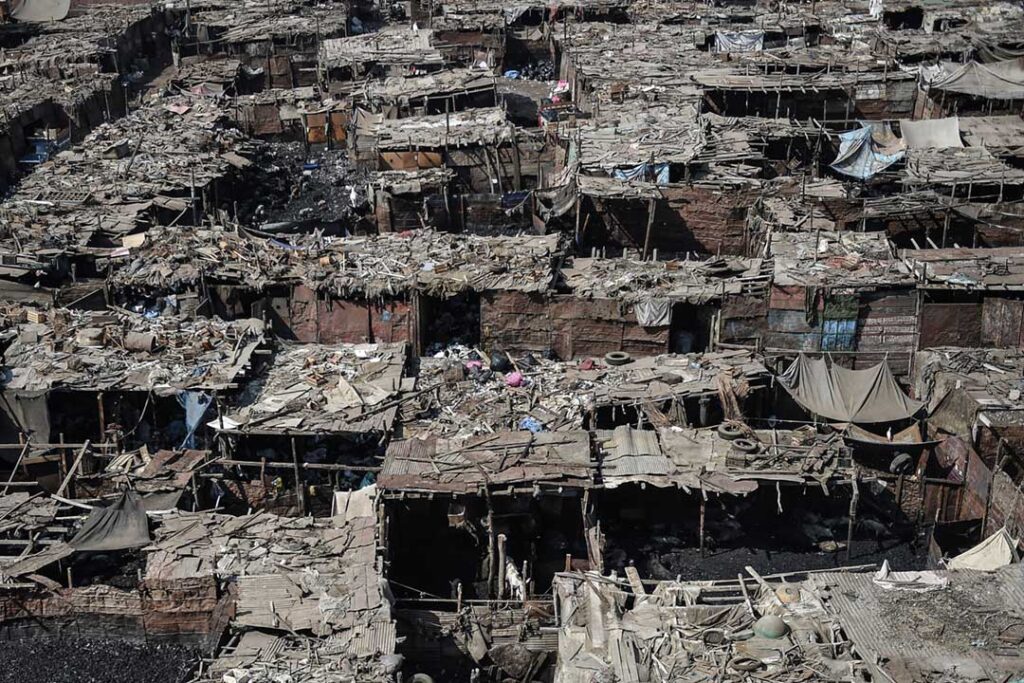

Egypt’s sprawling slums

The country’s new rulers need to change their perception of informal urban neighbourhoods

Izbit Khayrallah’s main commercial street is dusty and rutted. A pool of water partially covers the dirt and gravel road. About650,000 inhabitants live in this crowded neighbourhood perched on a rocky plateau on the southern outskirts of Cairo, according to Khayr wa Baraka (“peace and plenty” in Arabic), a local non-profit development group. Yet the neighbourhood, mostly brick and grey cement buildings, has no functioning sewerage system, no hospital and just one school.

Four decades ago migrant workers from Upper Egypt first settled here on what was then little more than state-owned desert sand. Despite government neglect, residents have built a community here after years of investment and collaboration. Without legal ownership of the property, however, they live under the constant threat of demolition by the state.

“After the 1973 [Arab-Israeli] war, people moved to this deserted area,” said Mohamed Abdel Halim, a lawyer and Izbit Khayrallah resident. “There was nothing. They made it their home. When it became more populated, when it was seen as desirable land, that’s when it caught the attention of the government.”

Since moving here in 2002, Mr Abdel Halim has been fighting the governorate of Cairo, which accuses residents of illegally building on state land. “We’ve fought for those whose homes were going to be demolished and won.”

Mr Abdel Halim is alluding to events in 1982 when women formed human shields to stop the first planned demolitions and prevent police from arresting men who were standing in front of bulldozers. The residents then went to court asking for an end to the demolition orders and demanding ownership of the land. The court ruled to end the demolitions and continued to consider the case to grant ownership rights.

Eventually in 1999 the court ruled that Izbit Khayrallah residents could buy the land, but the court ruling has never been implemented, leaving the residents without titles to their property.

Just one of countless informal communities sprawling across Egyptian cities, Izbit Khayrallah’s struggle for property rights highlights the growing clash between laws and court rulings, state and private interests, and the right of millions of Egyptians to own the land they have lived on for years.

President Abdel Fattah al-Sissi—when still defence minister—announced a plan last March to provide a million housing units to poor Egyptians. But critics say neglecting the rights of the residents of informal neighbourhoods could lead to further unrest.

With a fast-growing population and a large gap between property supply and demand dating back to the 1950s, Egyptians have long turned to building settlements illegally on agricultural land or government-owned desert land.

Amid lax regulations since the country’s 2011 revolution, informal areas have mushroomed: 700,000 cases of illegal construction have taken place on about 29,486feddans(70,205 hectares) of land, according to 2013 figures from Egypt’s ministry of agriculture.

“Despite [the figure] being significantly challenging to quantify, urban planners now estimate that around 75% of those living in greater Cairo live in informal areas,” said a property market source who spoke on condition of anonymity. “Yet they remain unrecognised by state institutions and have not been drawn on official maps.”

Without state recognition of their ownership rights or legal tenure, those living in informal settlements are denied basic services such as water, electricity and proper sewerage systems. In some areas, like Izbit Khayrallah, where residents have invested their own money—often their life savings—to build homes and amenities, their property has been under constant threat of demolition.

“There is a complex set of laws governing land ownership and a history of operating informally, which has led to the high percentage of Egyptians living without formal tenure of their property, whether it is rented or owned,” said Yahia Shawkat, a housing and land rights researcher at the Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights (EIPR), a Cairo-based NGO. “When push comes to shove, if a state agency claims that this land is state land, it can be possessed and taken” with the government claiming residents do not have tenure.

The threat of razing informal property depends on the residential community’s legal status and the importance of its location and value to real-estate developers. For example, Izbit Khayrallah is a mountainous and strategic area. There have been several plans to turn the area—with its view of the citadel and the pyramids—into a tourist development. “Businessmen affiliated with [deposed president, Hosni] Mubarak wanted to take the land and make a profit,” said Mr Abdel Halim, explaining why he believes the government wanted to flatten the neighbourhood.

After a deadly landslide in September 2008 in Manshiet Nasser, another sprawling Cairo slum, a presidential decree set up the Informal Settlements Development Facility (ISDF), a government task force. The ISDF identified 404 unsafe areas across the country, including 116 in Cairo, and since then has carried out sporadic evictions and demolitions—including in Manshiet Nasser. After compiling media reports and first-hand accounts, the EIPR’s Mr Shawkat has documented 6,435 cases of home demolitions in Egypt as a result of ISDF projects since 2008. The government has not released data on the number of home demolitions that have taken place and did not respond to data requests.

In the chaotic aftermath of the 2011 revolution, many people started constructing multi-storey buildings here without seeking the required permits or adhering to safety standards that may raise construction costs.

Whatever the reason for the demolitions, most residents in informal neighbourhoods say they feel marginalised, neglected and afraid. “The informal areas have always been seen as something negative, as a problem, rather than…as areas where millions of people live, where people have invested in building communities, and seeing those areas as assets, not just as slums,” said Diane Singerman, associate professor at American University in Washington, DC. “And that’s a very problematic way of seeing areas which are actually very mixed.”

As a first step the government should change its perception of informal areas, said Kareem Ibrahim, an activist and a project leader at Tadamun (“solidarity” in Arabic), a Cairo-based urban rights group.

“Informal neighbourhoods represent a significant portion of the Egyptian economy and the government needs to acknowledge the investment, the contribution from these neglected communities,” he said.

Egypt’s new constitution, passed in January, may open the door to improvements. Article 78 says “the state shall devise a comprehensive national plan to address the problem of unplanned slums, which includes re-planning, provision of infrastructure and utilities, and improvement of the quality of life and public health”.The constitutionsays private property cannot be sequestrated “except in cases specified by law, and by a court order. Ownership of property may not be confiscated except for the public good and with just compensation that is paid in advance as per the law.”

But this document does not define or specify who determines “public good”, leaving this section vague and open to interpretation.Article 63 prohibits “arbitrary forced displacement” but allows state authorities to justify some forced evictions. The new charter does not help the residents of informal areas obtain title to their homes, unlike the constitutions of other countries, such as Morocco, that have faced similar problems and found inventive solutions.

“Some things have been strengthened in the constitution,” Ms Singerman said. “But will it be implemented? That is the question.”

Now the onus is on Egypt’s citizens to ensure the constitution is interpreted in a way that benefits the communities, Tadamun’s Mr Ibrahim said. “We have these definitions in the constitution, but people don’t know what it [the constitution] means. They don’t know their rights,” he said. “It should be a bottom-up process. Civil society and local governments need to be engaged…in dialogue so we can [find] common ground.”