Rape: the South African scourge

by Ivo Vegter

South Africa has a reputation for the world’s worst sexual violence rates against women, men and children. Amid confusing data and complex causes, what is it that makes South Africa unique?

Pinning down the statistics is hard. They often come in an inconsistent and context-free form: one person is raped every 17 seconds, or 26 seconds, or 36 seconds, or 65 seconds, depending on whom you believe. Such formulations are good for sloganeering, but say little about the reasons behind this cruel crime and even less about how to solve the problem.

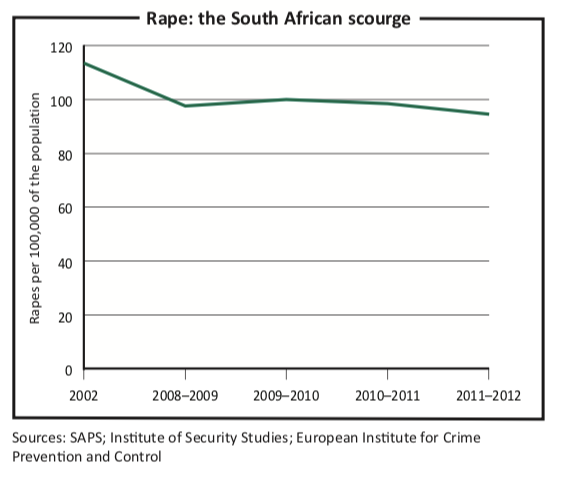

Some surveys find statistics a hundred times higher, but official South African Police Service (SAPS) statistics claim 95 rape cases per 100,000 of the population in 2011–12, a slight decline from a peak of 100 cases per 100,000 in 2009–10. That works out to 48,060 cases per year, or one rape every 11 minutes.

But there is concern that data compiled by police officers, whose own performance is under evaluation, may be unreliable.

More generally, however, statistics depend heavily on whether or not crimes are reported, and sexual crimes often are not. A study by the Institute for Security Studies, an African research organisation, states that “sexual offences suffer from low reporting rates and the crime statistics are thus not a good indication of the actual number of cases.”

The Medical Research Council (MRC) estimates that only one in 25 rapes is reported. Other human rights groups claim the number is one in nine. For all the contradictory data, the MRC calls the South African situation “a globally unprecedented problem of violence against women and girls”.

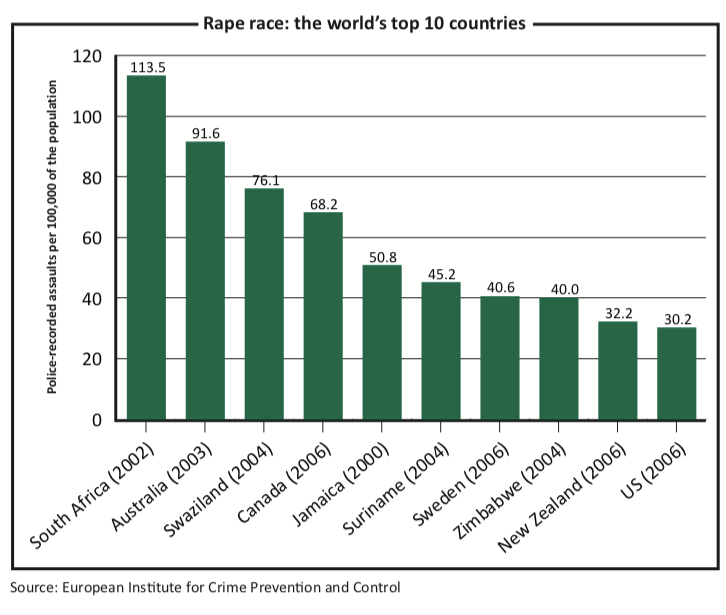

South Africa’s reported rape rate is higher than runners-up Australia, Swaziland and Canada, according to the UN’s European Institute for Crime Prevention and Control. The North American rate exceeds that of southern Africa. Such comparisons are just as confusing and contradictory as the raw data, revealing barely enough to conclude that rape appears to be unusually common in South Africa.

What is it that makes South Africa unique? In a recent series of discussions with a rape victim—let’s call her Chrissy—we explored some of the reasons why rape is such a scourge in this country. Violence, including rape, is often seen as correlated with high poverty and unemployment, as well as high income and gender inequality. The MRC notes that while the “middle classes are often most vocal about the problem of violence, the overwhelming majority of victims are found among the working classes and the poor”.

Cultural norms emphasising male dominance and female submissiveness are also strongly associated with sexual violence. The same is true for carrying weapons, drinking, and drug use, according to the MRC researchers.

Rape cases are notoriously reliant on the victim’s word against that of the perpetrator, which makes them difficult to prosecute successfully. However, matters are made much worse by: unreliable forensic evidence; role models such as President Jacob Zuma, who stood trial for rape while his political allies attacked his accuser; as well as appointments like Chief Justice Mogoeng Mogoeng, who has a record of reducing sentences because of dubious mitigating socio-economic circumstances of rapists.

Prosecutorial difficulty occurs even before cases are reported. According to Antony Altbeker’s book, “A Country At War With Itself”, which is regarded as an authoritative account of South Africa’s crime problem, a widespread social acceptance of violence means that the communities often protect perpetrators while “law enforcement is generally very weak”.

Corruption and lack of resources aggravate the problem. The consequence, according to Mr Altbeker, is that reporting is infrequent, punishment is rare, the law fails to deter would-be criminals, and victims have little faith in the system.

The MRC says more research is needed into the social causes of violence: “poverty, youth unemployment, gender and other social inequity, dominant ideas about manhood, exposure of children to trauma and abuse, harmful levels of alcohol consumption, social norms on the use of violence, access to firearms, as well as the weak policing and legal responses”.

While these issues are common to other jurisdictions, they do not lead to equally high levels of rape. Even harmful myths such as that intercourse with a virgin will cure someone of AIDS are not unique to South Africa. They are also pervasive in Nigeria, Zambia and Zimbabwe, according to researcher Suzanne Leclerc-Madlala.

So, what is it that makes South Africa different? “Apartheid, of course,” replies Chrissy. “We’re so blinded by the rainbow that we forget the damage caused by the past.”

In a 1994 paper published in the journal Focus on Gender, Sue Armstrong blamed the militarised and conflict-ridden society prior to liberation that gave rise to an exaggerated culture of aggression and male dominance, among both black and white. “It was unquestionable that rape was intertwined with the racial injustice of the apartheid system,” she writes.

Many “comrades” also condoned rape during the “people’s war” against apartheid, which hindered the policing of crimes and further anchored violence.

So why do such high rates persist two decades after liberation? Chrissy, who comes from a conservative background, holds the breakup of the family unit responsible. “Men became migrant labourers in the cities and on the mines,” she says, “leaving children behind without fathers, or without any parents at all.” However, family violence has worsened since 1994 and not only because of the migrant labour system.

Political analyst Eusebius McKaiser, writing in the Los Angeles Times, put it in psychological terms: “Both the victims and the perpetrators of violence, state-sanctioned or personal, rarely escape their earlier experiences entirely without professional intervention. South Africa is showing symptoms of post-traumatic stress on a grand scale.”

Vulnerability of children who are orphaned or abandoned by poor, working or shiftless parents is a major factor that feeds into high rape incidence, MRC researchers agree. Mr McKaiser adds: “Archaic patriarchal notions are prevalent—men ought to be bread-winners, strong and independent—leaving many men not only to struggle through their poverty but also to feel grossly inadequate.”

A history of submission and degradation has reinforced this inadequacy. Haunted by inferiority complexes and an inability to play the traditional role of the provider for their families, some victims of apartheid’s oppression exhibit compensating behaviour that is loud, violent, aggressive and domineering, especially towards women and children.

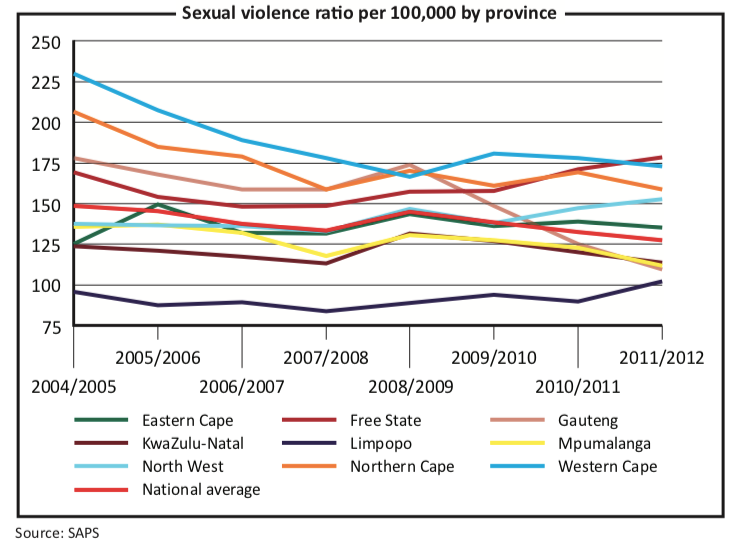

Quantifying rape with cold numbers is fraught with contradiction. It is un- doubtedly one of the worst non-lethal crimes on the books. In South Africa the crime ratio of sexual violence including rape in 2011–12 was 127.5 per 100,000, an unacceptable level. Whatever the numbers, the incidence is much too high for complacency.

However, it is also clear that dealing with the scourge of rape is not a simple matter of “getting tough on crime”. On the contrary, as the MRC observes, that kind of language itself reinforces the violent machismo that contributes to sexual crimes.

New ideas and commitments are needed, the MRC says. Despite the myriad and complex reasons behind sexual violence, we do not escape moral responsibility, Mr McKaiser concedes. His solution however, is little more than “a fuller public conversation about the scars left by our violent collective past”.

That is a small plaster for a gaping wound. The lack of ideas, rather than just alarming data, may explain why policymakers appear so impotent and activists so often display only anger and despair.