Democratic Republic of Congo: Allied Democratic Forces

Another little-known rebel group wreaks havoc in the eastern Congo

The M23 is the armed group which has featured most prominently in the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) in the past year. This rebel group of several thousand, with close links to Rwanda and a long history of destabilising North and South Kivu provinces, recently ended its 18-month insurgency.

But just a bit further north, up the road towards the commercial trading centres of Beni and Butembo, in what is known as the Grand Nord, is the home of one of the oldest armed groups in this volatile region, the somewhat less well-known Allied Democratic Forces (ADF). Its presence in the DRC dates back to the 1995, when a sick and beleaguered Mobutu Sese Seko was still in power in Kinshasa, the capital. Its main enemy, the government of Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni, has declared it dead many times. But it has made a dramatic comeback in the last several years, which has prompted observers to speculate about the source of its newfound strength.

Yusuf Kabanda, who spearheaded the Islamic opposition to Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni, founded the ADF and merged it eventually with the National Army for the Liberation of Uganda (Nalu), another anti-Museveni armed group, which had been based in Congo since the late 1980s. Mr Kabanda was capitalising on frustrations within the Ugandan Muslim community, which had been the target of crackdowns by the governments of Mr Museveni and his predecessor, Milton Obote. Unable to gain a real foothold in Uganda, and facing heavy pressure from the Ugandan People’s Defence Force (UPDF), the ADF settled across the border in the DRC’s remote and mountainous Rwenzori Mountains.

There it eventually merged with the National Army for the Liberation of Uganda (Nalu), which had been chased out of Uganda in 1988 and was then based in the Congolese towns of Beni and Lubero. The new movement became known as the ADF-Nalu. Both groups were anti-Museveni at a time when the Ugandan president was a key post-Cold War ally for the West in Africa. Beyond this main ideological commonality, the two groups had no operational links. They were united by their presence on Congolese soil and two mutual allies: the al-Turabi government in Khartoum, Sudan, and the Mobutu government in Kinshasa.

Nalu had emerged from the Kingdom of Rwenzururu’s decades of opposition to Kinshasa’s central authority and the autonomy it sought from the post-independence Ugandan government. The struggle ended in 1982 when Ugandan President Obote recognised the kingdom’s autonomy. After Mr Museveni overthrew Mr Obote in 1986, Mr Obote’s former intelligence chief, Amon Bazira, created Nalu and recruited some of those who had previously fought for Rwenzururu autonomy. The Kenyan and Congolese governments, which did not trust the Museveni government, a result of long-standing clashes of personality and ideology, provided Nalu’s initial financial and military support. Nalu staged 43 grenade attacks in Kampala, the Ugandan capital between 1990 and 1993, its most active period. But the Ugandan military ultimately defeated Nalu and Mr Bazira was assassinated in Kenya in 1993.

The ADF meanwhile grew out of the increasing oppression of the Ugandan Muslim community, first by Mr Obote from 1979 onwards and then by Mr Museveni, who took power in 1986. But the struggle for dominance within the Muslim community led to violent clashes between rival groups in the early 1990s. This led to the imprisonment of key youth leaders, notably Jamil Mukulu, who had been the leader of the youth branch of the Tabligh Muslims, a movement which preaches an orthodox interpretation of Islam. The Tabligh movement enjoyed the financial support of Sudan’s Muslim-dominated government, which allowed it to recruit young Ugandans into its fold and gave it greater influence in the community. This put it at odds with other Muslim groups. When the group was released from prison, it established an armed group—the Muslim Liberation Army of Uganda (MULA) in western Uganda. But despite significant support from Khartoum, Uganda’s army defeated the MULA in 1995.

In September 1995 Mr Kabanda’s ADF entered into an alliance with Nalu in Congo’s North Kivu province.

In subsequent years, the eastern DRC operated as the base for ADF-Nalu’s 4,000-5,000 combatants to launch attacks into Uganda, according to the International Crisis Group. However, in spite of its relative strength, and although it carried out a number of smaller-scale attacks into Uganda, the ADF-Nalu was never a real threat to the Museveni government. In 1999, at the height of its military campaign, it launched a series of grenade attacks in Kampala. This prompted the Ugandan army to mount a major military operation against the ADF-Nalu in the Rwenzori Mountains. A large number of combatants and some senior leaders died during the battles. At the same time, the Ugandan government succeeded in cutting crucial Sudanese logistical support to the ADF-Nalu, thereby severely handicapping the movement.

In the following years, significantly weakened by the loss of its key Sudanese supporter, ADF-Nalu attempted to survive by creating alliances with several of the Rwandan-backed armed groups also operating in the eastern DRC, notably the largest one, the Congolese Rally for Democracy (RCD) which then controlled large parts of the eastern DRC. It also increasingly turned to crime to support its activities. By 2001, the Ugandan government announced that ADF-Nalu had been reduced to 100 combatants.

Since then the movement has recovered some of its strength, recruiting disaffected youth and demobilised combatants. This has prompted the United Nations Mission in the DRC (MONUC, now the United Nations Stabilisation Mission in the DRC – MONUSCO) and the Congolese national army (FARDC) to launch a series of targeted military campaigns against the ADF in 2005, 2007 and 2010. A number of combatants have also chosen to voluntarily disarm, including the last remnants of Nalu, which effectively ceased to exist in 2008. Since then, the armed group is simply referred to as the ADF.

Fighting between the Congolese army and the ADF and its new allies—several Congolese self-defence units known collectively as Mai Mai groups—peaked again in 2010. The fighting displaced over 100,000 people and led to widespread human rights abuses. This prompted the launch of “Operation Rwenzori”, another joint FARDC- MONUC operation, which lasted until 2011 and in which both sides incurred heavy losses.

Although the Congolese government has invested resources in trying to eliminate the ADF, this is part of a greater effort to re-establish its authority in the eastern DRC. The Congolese government has never really perceived the ADF as a threat to power in Kinshasa, although it has been unhappy about its hold on key trade routes. Lucrative commerce in timber, and to a lesser extent gold, form part of the ADF’s economic network in eastern DRC, according to a 2011 UN report.

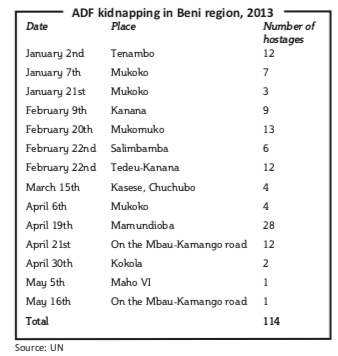

But ADF attacks on several Congolese villages and schools, on the rise since late 2012, as well as its killing and kidnapping of civilians in the last six months, have again shone the spotlight on the group. The ADF briefly took control of the eastern DRC towns of Kamango and Kikingi last July, displacing tens of thousands of people and engaging in drawn-out battles with the FARDC. More recently it has continued its attacks on hospitals and schools, prompting MONUSCO to condemn the attacks. The UN’s intervention brigade in the DRC is also mandated to pursue the ADF.

Although the ADF has not attacked Uganda since 2007, Kampala has historically found it useful to present the group as a greater threat to national security than it actually is and has maintained that its presence in the eastern DRC is a legitimate security concern. Mr Museveni has used this argument to defend his country’s ongoing interference in its neighbour’s affairs.

Most likely for geostrategic reasons, Mr Museveni has made much of the ADF’s religious links in recent years, attempting to paint it as a radical Islamist movement with ties to terrorist groups. The Ugandan government has sought to present the ADF as having clear alliances with the Somali extremist group, the Shabab. To date, such connections have not been verified independently: the majority of reports to this effect have come from Ugandan security forces.

Many reports have focused on ADF leader Mr Mukulu, who Uganda alleges is al-Qaeda’s number two in East Africa. Experts on Islamist movements in Somalia have not confirmed these allegations, according to an International Crisis Group 2012 briefing: “the existence of direct cooperation between the Shabab and ADF remains only a hypothesis, especially as the Ugandan government uses the terrorist threat for both domestic and external policy reasons.”

A look at the ADF’s internal working also does not indicate that it has become a radicalised religious movement at present: the movement does not require its members to be Muslim or to adhere to the Koran. Nonetheless, recent events in Kenya, coupled with an upsurge in attacks, kidnappings and killings in the Grand Nord of North Kivu province, are likely to mean that the ADF will be subject to greater scrutiny.

[author] [author_image timthumb=’on’][/author_image] [author_info]Stephanie Wolters is a journalist and researcher specialising in African conflict zones. From 1998 to 2004, Stephanie worked in the DRC for the BBC, The Economist, and then as the news editor for Radio Okapi. Stephanie is programme manager of the Conflict Prevention and Risk Analysis Programme at the Institute for Security Studies.[/author_info] [/author]