Central African Republic’s natural resources

In a country mired in violence and chaos, property laws do little to protect underground treasures from predatory interests

The problem with land, or rather “space”, in the Central African Republic (CAR) becomes apparent immediately upon leaving the airport. On the apron side, where shiny planes with acronyms emblazoned on their tails wait for take-off, all is tended planters and graded asphalt. On the far side of the terminal building, Bangui begins: tens of thousands of men, women and children—all belonging to a cohort that human rights organisations term “internally displaced persons”, or IDPs.

Since March of 2012, when the capital was ripped apart by the battle that ended the regime of President François Bozizé, these masses have shifted around the country like pieces on a chessboard. In December 2013 almost 100,000 IDPs crowded into a camp that formed at the airport gates. They were nestling as close as possible to Camp M’poko, the French military base that functions as the headquarters of its Operation Sangaris, named after a local butterfly. Almost 10,000 foreign troops—the European Forces, the African Union and the French—are in CAR to slow what was tipping towards a genocidal civil conflict. A contingent of UN peacekeepers was expected in September, soon after this story went to print.

CAR has endured a history of coups, one-party rule and murderous regimes since independence in 1960. This has paralysed the country, leaving it with weak government institutions and insecure land rights. CAR is currently riven by what has been described as a religious conflict between the Muslim Selekarebels (Alliance in the Sango language) that flooded from the north, and the Christian anti-Balaka militias that formed to counter the new waves of violence after the insurrectionists toppled Mr Bozizé.

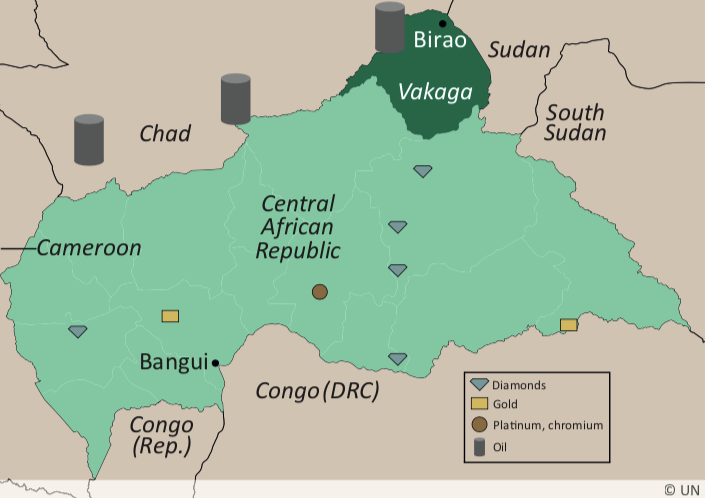

Nominal Selekaleader, Michel Djotodia, won the Presidential Palace in March 2013 but quickly lost control of his forces. Catherine Samba-Panza replaced him in January 2014. But a visit to the main Selekabarracks in Bangui, a ramshackle operation spilling out on either side of a mango tree-lined avenue, allows that the Selekaare just as Christian as they are Muslim. This rebel coalition grew out of the immense dissatisfaction with the pace of development, to say nothing of the foreign cherry-picking of CAR’s underground bounty—diamonds, gold, oil and other resources.

Seleka’spoint is apparent even if their methods are disagreeable. Despite all the hidden bounty, CAR remains one of the ten poorest countries in the world, and is in the bottom 1% of almost every development indicator. Eighty percent of its 4.6m souls are subsistence farmers or nomadic pastoralists. This means that when they flee violence, they leave with nothing. Starvation and humanitarian crises immediately begin stalking the ragged trail of IDPs the moment they go on the run.

The solution to many of CAR’s problem lies not under the land, but on top of it. “Greater security of land tenure rights could help to increase investments for productivity, especially in small irrigation facilities and for women farmers, but an array of other interventions will also be needed to improve the productivity and performance of the agricultural sector overall,” notes the website of the US Agency for International Development (USAID). These sentiments were difficult to implement before the latest conflict. They are close to impossible in the current climate.

Although Ms Samba-Panza installed the country’s first Muslim prime minister, Mahamat Kamoun in August, this has not appeased Seleka. Land rights in the CAR may explain why. Property laws are badly structured and thus endlessly mutable. Throughout the CAR’s 54-year history, land has meant power and power resides in Bangui.

Think of it this way: groups from the north, many of them Muslim, have felt endlessly marginalised because they have no land security.In the scramble of letters that articulate Seleka’s founding coalition, land issues roused groups in the country’s remote and disconnected regions.

The Sangaris have confined Issa Issaka Aubin, a Selekageneral, and his troops to barracks on the outskirts of Bangui. He is convinced that the only way to quiet the conflict is to adopt the resolutions tabled at a conference in Brazzaville, Republic of Congo, in July, which included disarming all rebel groups and the repatriation of foreign fighters that move back and forth across the country’s porous borders. (Central Africa is terminally locked in a low-level international conflict with Sudan; Uganda’s Lord’s Resistance Army has roamed its border since at least 2008). So far, General Aubin claims, nothing has been done. “In my native region,” he says, “you’ll see there’s no road, no schools, no rights, no nothing.” Home for the general is Vakaga, a north-eastern region rich with oil. He finds himself in a race against the petro-curse: if the local population’s land rights are not secured, another oil-soaked free-for-all is in the offing.

The French claim to have secured the roads into Bangui from the east, west and, most importantly from Cameroon in the west—the source of much of CAR’s $2 billion GDP. But for locals, this seems like a cynical ploy to ensure the smooth passage of resources out of, not into, CAR. The war has exploded all the old colonial tropes into an IMAX mega-movie. What remains, according to USAID, is an out-dated framework for land rights—a noisily ticking time bomb that promises to blow the country properly to pieces.

The 2004 constitution insists that all citizens have a right to property but, according to USAID, law No. 63 remains the primary legislation governing land rights in CAR. Dating back to 1964, this law recognises customary law, but limits customary land tenure to use-rights. State land can be privatised through land registration.

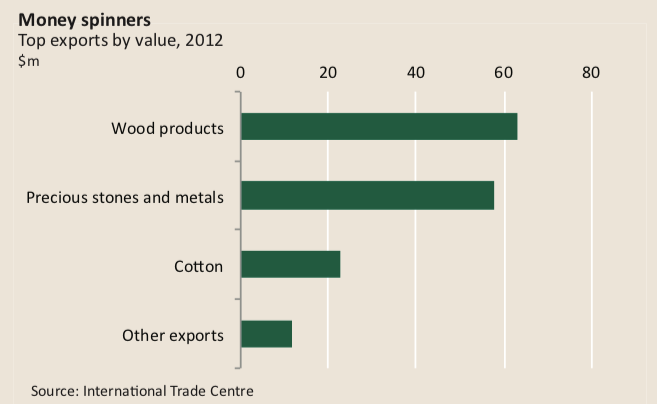

The issue, as far as USAID’s land tenure analysts are concerned, can roughly be divided into three main concerns. The first, and perhaps easiest to address, is the legal structure of land and forest rights. CAR’s byways bustle with men pushing wood to market in Bangui. The re-upped 2008 code, however, does little to protect CAR’s citizens from predatory interests, particularly in the timber industry, the main source of export earnings. It does even less to protect them should infrastructure projects be implemented in their regions.

USAID has four main recommendations: refocus on “customary laws and traditional institutions”; establish a framework for the rule of law and realise the constitution’s principles of fairness; integrate a decentralisation policy that allows power to trickle up; protect and improve the rights of the country’s more marginalised demographics, like women, children, pastoralists and forest dwellers.

Implementing those recommendations might address certain Selekagrievances. So would tacklingthe urban and extra-urban informal settlements that spring up, most notably around Bangui, every time the country tips over into conflict. Dozens of African countries have the same problem but few have weathered the CAR’s IDP storm.

While the state recognises the right to habitation by providing a permit that allows the holder to build a small structure on a regulation-sized plot, these are almost impossible to obtain in urban areas. Formalising land tenure for those “squatting” on the urban fringes might integrate migrants into the larger national project, while offering them the security they need to be melded into the larger economy. They would no longer be outsiders, but members of a greater whole, with access to sanitation, running water and electricity—in so far as these amenities exist in the CAR.

Perhaps most critical, is how desperately the CAR needs to prevent the conflagrations that are certain to spark up around any newly prospected area. This is a country that is barely aware of what wealth lurks underground, and every time someone smells resources, land tenure issues rise to the surface. It makes sense to reconceive the constitution’s reference to “customary rights” as a trickle-up model that ensures community involvement in resource management.

Stare at the situation long enough and the CARs problems can largely be whittled down to two: issues: how the state hands out concessions and leases to individuals and corporations with vested interests; and how Bangui defines land that is “not put to proper use”—land that sits fallow or is not mined or logged quickly enough.

Very simply, the CAR’s unloved and mistrusted politicians have far too much power to appropriate and redistribute land, especially land that holds abundant natural resources. To men like the Seleka’s General Aubin, the current chaos seems like an unbroken stream of colonial or neo-colonial thievery that has lasted centuries. When asked why, 54 years after independence the French are still occupying the airport and pacifying Bangui with armed men, he says, “You tell me. We don’t see any change. We don’t want to be a ‘partner’ with France.”

If the country’s regional districts, a nice way of saying “ethnic cohorts”, are not given a bigger voice in governing their land, the country is doomed. In addition, CAR’s borders need to be managed in a much more coherent way. “Transhumance”, as the wonks describe the sub-legal movement of humans and their herds across borders, has been a constant cause of friction in CAR. If the government’s laws and regulations regarding land use by pastoralists were better considered, these conflicts would be minimised.

“But while national authorities, located hundreds or thousands of kilometres away from the rural areas affected, ignore frequent violence related to pastoralism, local populations, which are the main victims, cannot afford to do so,” according to a June report by the Brussels-based International Crisis Group. “Deep-rooted issues can degenerate into intercommunal conflicts, and constitute a major factor in the confrontation between the Fulanis and anti-Balaka militias in CAR.”

Ms Samba-Panza has her hands full. And the inevitable has, of course, happened. On August 18th, Michel Djotodia, the ex-president, formed the new breakaway state of Dar El Kouti, in north-eastern Birao, where the oil bubbles up. This makes it even more urgent for the national assembly to move forward on land rights just as quickly as on reconciliation. The two cannot be separated. If CAR hopes to have a future, it will come from the land, in the form of bountiful natural resources that will power its nascent economy and by the sense of fairness that will emanate from equitable laws. Mr Djotodia has made his play: CAR is Balkanising. Fragmentation will bring endless war. The land can knit the country together.