With megacities such as Lagos, Nairobi, Cairo, Kinshasa, Luanda, Johannesburg and Dar es Salaam set to become increasingly important continental economic hubs, this looming explosion in urbanisation has created a set of unique challenges for policymakers and businesses across Africa. Indeed, as pressure for limited resources intensifies due to population migration, there will be a growing need for innovative and sustainable solutions to ensure these potential gains are met. Transport, housing, and financial inclusion are all set to be key priorities as African cities look to transform themselves, achieve prosperity, and avoid socio-economic distress.

Against this backdrop, what can African cities learn from the likes of Medellín and Singapore (and other global success stories) and which cities on the continent are on track to succeed?

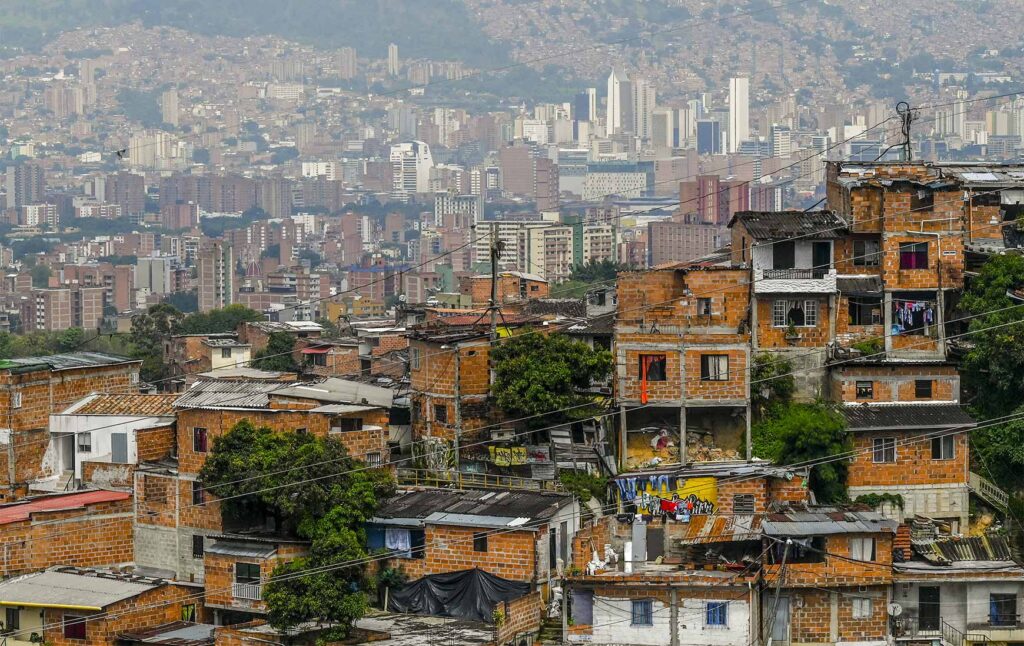

In the early 1990s, Medellín in Colombia was classified as the most violent city in the world. The homicide rate climbed to 381 murders per 100,000 people in 1991, close to 40 times greater than the UN’s definition of endemic violence, at 10 per 100,000 people. Much of the violence can be attributed to the reign of Pablo Escobar, who used Medellín as a base for his drug-related and criminal activities. The illicit trade and turf wars between Escobar’s cartel and the state led to dizzying levels of violence that hurt the poorest parts of the city the most. These days, Medellín is an attractive city with its open botanical gardens, library parks, and enterprising business climate. From being the most dangerous city in the world to becoming a world-class smart city, the transformation of Medellín has been staggering. Just how did a city ruled by crime and drugs turn into a digital nomad haven and tourism mecca in such a short period?

The first factor, which cannot be underestimated, is politics. The combination of urban planning at the local level, security at the federal level, and a truce among gangs on the ground set the foundation for this remarkable transformation. Indeed, the creation of a new social contract was central to the maintenance of peace and drastic improvement in living standards in the city.

Following Escobar’s death, the demobilisation of guerilla groups, major policy changes, the addition of social programmes, and serious infrastructure investments all facilitated greater political and economic stability across the country. With improvements in macro factors, the local leadership of the city undertook a series of ambitious and bold reforms. Several city mayors, starting in 2000, took listening to their constituency seriously. They revamped the city’s education system, implemented initiatives to guide youth away from gangs, upgraded healthcare systems, added millions of square feet of public spaces and renovated parks, built new museums and sports facilities, added electric buses and a citywide free bike-sharing service plus 60 miles of bike lanes. While mayor from 2003 to 2007, Sergio Fajardo adopted the slogan “from fear to hope,” and the sentiment set in as public projects revitalised the city.

Given the newfound stability, conditions were fertile for new investments – the second key priority. Big bets were made on infrastructure investments for public safety. The city also prioritised technology and innovation to improve governance.

For example, Medellín looked across alternative industries and decided to repurpose chairlift technology, conventionally used in ski resorts. Using the existing technology, Medellín built the world’s first urban cable car system (Metrocabal) dedicated to public transport at half the cost of a comparable railway system. The same innovation was used to improve the security landscape across the city by using data to create more efficient crime monitoring systems. Authorities used GPS trackers, CCTV, facial recognition technology, and smartphones for police to make the necessary safety improvements.This attracted corporate partners and powerful multinationals and unlocked private-sector investment, particularly in infrastructure. Indeed, the city’s big spending spree in the mid-2000s was largely a result of a unique private-public partnership between the city and Empresas Publicas de Medellín (EPM).

The third factor was inclusion. The “Medellín model” prioritised building “a cross-class and cross-income coalition for change”. Whereas most smart-city initiatives assist the tech-savvy and well-resourced segments of the community, the transformation in Medellín has benefited chiefly those with the fewest resources. As momentum grew, new schools and cultural centres were built in the poorest areas by the best-known architects in the country. With each project, “the mayor’s office imagined integrated services so that a school would never just be a school but a place for health services, a community centre, a space for adult education.”

With support from microfinance institutions, entrepreneurship centres were set up in slums, providing business support and technical advice to locals. These centres led to the creation of more than 50,000 microenterprises. The city also opened up daycare centres to support and upskill underprivileged mothers and children, providing both resources and employment opportunities. The launch of a new public transportation system in 2004 to connect the city’s low-income neighbourhoods to the city’s central business district was a prime example of this integrated approach. The idea, according to local civil servants, was to provide dignity and value to the most marginalised and to dispel the idea that poor people deserved the poorest things.

The significance of Medellín’s transformation cannot be overstated. Through bold moves in architecture, planning and urban design, it went from lost cause to becoming, in 2012, “Innovative City of the Year”. As architect Alex Warnock-Smith noted in a 2016 piece for the Guardian, an integrated multidisciplinary approach was central to the city’s success. Specifically, an approach of “radical urbanisation” and “an attitude towards urbanism as a tool for promoting social mobility and equity – a process in which comuna dwellers became clients, participants, and stakeholders in the city, with the chance to design their own destiny” was a central feature of the city’s success. “

Singapore is another success story. Policymakers had two key priorities: the first was a focus on making people’s lives liveable, and the second was helping the land become sustainable. Through smart and pragmatic design, an efficient state, and long-term thinking, Singapore was able to achieve these goals.

The first thing policymakers did was recognise and adapt to their unique conditions. They recognised that living environments would need to be designed for a high-density city. However, many planners expressed concern that by creating high-rise public housing blocks, Singapore was creating conditions ripe for a different kind of urban slum.

The Housing and Development Board (HDB) was established in 1960 to oversee the construction of public housing. By the 1980s, more than 80% of Singaporeans lived in HDB flats. This approach to public housing was innovative in many ways, including the use of prefabricated building components to speed up construction, the creation of high-density but liveable communities, and the provision of public amenities such as schools, parks, and community centres. The focus was on providing residents with homes. By 1990, 88% of residents owned their homes, and the number has stabilised at around 90%, one of the highest home-ownership rates in the world.

A strong focus on protecting the environment meant attempts were made to limit air pollution and increase green cover across the city. This, coupled with Singapore’s early investment in essential infrastructure, like public transport, sewers, water and electricity, enabled it to transform into a first-world city in a short period.

In more recent times, Singapore has adopted a smart city model, which describes a city that uses technology and data to improve the quality of life for its residents by making the city efficient, sustainable, and liveable. A smart city incorporates a variety of technologies in its design, such as sensors, data analytics, Internet of Things (IoT) devices, and artificial intelligence (AI) systems, to collect and analyse data about the city’s infrastructure, environment, and residents. This data can be used to make informed decisions about how to improve city services, reduce energy consumption, optimise transport systems, and enhance public safety, among other things.

As noted by researchers Sarah Colenbrander and Ian Palmer, African cities will gain a billion new residents by 2050. But local authorities across the continent don’t have the resources, powers or skill sets to meet the growing demand for housing and services. Against this backdrop, what lessons do the examples of Medellín and Singapore offer for African cities?

Five key learnings stand out. First, to become a competitive, efficient, and equitable economy with a harmonious society requires good governance and efficient public administration, supported by resilient public and private institutions. There is quite clearly no substitute for political will and bold, visionary leadership. African cities have a long way to go in this regard. Barring a few exceptions, the quality of political and technocratic leadership both at a state and local level is simply not fit for purpose and will need to be significantly upgraded.

Second, African cities must embrace technology. This argument is compellingly made by the collaborative African research hub, Intelliverse AI, which argues that in African cities, “the amalgamation of rapid population growth, limited resources, and outdated infrastructure has given rise to complex challenges. From sprawling traffic congestion to energy inefficiencies and strained public services, the urban fabric has become a canvas awaiting the strokes of innovation. This is precisely where the promise of AI becomes compelling – not merely as a technological novelty but as a strategic force capable of reshaping the very essence of urban living.”

There are clear examples of how such tools are already employed in some cities. Cape Town’s open data portal stands out; through this, all data recorded in the city is made publicly available to its citizens. Furthermore, in response to water scarcity challenges, Cape Town now uses AI to monitor water usage patterns, predict shortages, and optimise distribution, thus enhancing its water conservation efforts.

In her analysis for Outside Insight, marketing and communications specialist Thea Sokolowski observes that Kenya’s smart city efforts are well underway. Konza Techno City on the outskirts of Nairobi, dubbed Silicon Savannah, is a proposed satellite city that will gather data from smart devices and sensors embedded in roadways and buildings, enabling optimisation of traffic and infrastructure, smart communication services, and improved citizen participation.

Smart cities and a tech-oriented approach are gaining traction across the continent, with Nigeria’s Eko Atlantic, Accra’s Hope City, and Kigali’s Vision City all emerging as ambitious hubs that aim to replicate the success of modern cities like Dubai and Singapore. According to Mira Slavov, a fellow at LSE, these initiatives are also giving rise to “a new model where governance is shared between the private and public sectors”.

Third, in the push to net zero, the imperative to design, build, and operate more efficiently and cost-effectively is the new norm. The need for sustainable cities is particularly urgent, considering cities generate more than 70% of global carbon emissions.

This shift from “pollution to solution” is important, especially since Africa’s citizens face higher exposure to climate risks than any other continent while having a lower capacity to adapt. The continent’s urban environments are particularly vulnerable to flooding, droughts, and outbreaks of diseases.

This speaks to the fourth lesson: the need to provide dignity to their citizens. As the Singapore and Medellín examples show, deliberate efforts were made to ensure that this was inclusive and helped the most marginalised in society. Bottom-up solutions and ‘dignity by design’ were central tents in both transformations.

Fifth, the right conditions for investment must be created. Given the extent of the challenges and the lack of fiscal resources governments face, there is a clear need for “out-of-the-box” solutions. Private sector investment across hard, soft, and digital infrastructure will be vital. To do this, governments and cities will need to provide clear incentives and regulatory certainty. Public-private partnerships must be prioritised, while data-backed strategies to enhance formal-sector participation and expand tax nets will need to be developed. Cities would also do well to replicate the success of cities like Johannesburg and Cape Town in using green bonds and using financial instruments to raise funds for development.

Given Africa’s demographic challenges and rapid urbanisation, the need for innovative, scaleable, and sustainable solutions is both urgent and obvious. Although the continent’s development path is unique, the case studies of Medellín and Singapore offer inspirational lessons on how to build inclusive, safe, and prosperous cities.

RONAK GOPALDAS is a director at Signal Risk, an exclusively African risk advisory firm. He was previously the head of country risk at Rand Merchant Bank (RMB) for a number of years, where he managed a team who provided the firm with in-depth analysis of economic, political, security and operational dynamics across sub-Saharan Africa. He holds a BCom degree in philosophy, politics and economics (PPE) and a BCom (Hons) from the University of Cape Town (UCT). He also has an MSc in finance (economic policy) through the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) in London.[