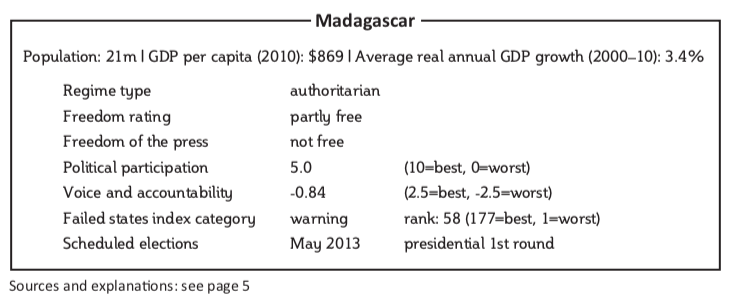

Madagascar, languishing since the 2009 coup, may hold elections in May 2013. Or maybe not.

by Annelie Rozeboom

Monday afternoon in downtown Antananarivo, Madagascar’s capital, and about 100 people are waving their fists in the air. They are standing in a parking lot littered with rocks and debris from looting three years ago. The Malagasy national anthem shrieks through loudspeakers in the ruins of a shop once owned by deposed president Marc Ravalomanana.

“You should come on a Saturday, that’s when this place is full,” says leader Henri François Randrianjatovo. Ever since rival Andry Rajoelina forced Mr Ravalomanana into exile in March 2009, the ex-president’s party has held daily rallies in front of this building. “It gives people hope,” Mr Randrianjatovo says.

Mr Randrianjatovo, once minister of youth and sports in Mr Ravalomanana’s cabinet, insists that Tiako-i-Madagasikara (TIM, or I love Madagascar) should be the ruling party. “We were elected and overthrown by the army, so we were forced into opposition,” he says. TIM has been the core of the opposition to Mr Rajoelina. Smaller parties of two other former presidents joined TIM to create the “Ravalomanana movement”. Its main goal: return the former dairy tycoon to power.

Economic development was high on Mr Ravalomanana’s agenda when he was sworn in as president in disputed elections on May 6th 2002, replacing the socialist Didier Ratsiraka, who had ruled the country for 23 years. He liberalised the economy and foreign investment poured in. In 2004 the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank cancelled $2 billion of Madagascar’s sovereign debt, largely as a result of Mr Ravalomanana’s adoption of free-market policies. Anglo-Australian miner Rio Tinto agreed to invest over $800m in a titanium dioxide mine. Paris-based petroleum giant Total started a tar sands project at the Bemolanga bitumen deposit on the island’s west coast. Several other oil companies began offshore exploration.

But it was another foreign investment plan, by South Korea’s Daewoo Logistics, that sparked Mr Ravalomanana’s downfall. Mr Rajoelina, a disk jockey turned big businessman and then elected mayor of Antanarivo, had his eyes on the presidency.

He used Daewoo’s proposed 99-year lease of 3.2m acres of land for maize and palm oil plantations to rally opposition to the government. Riding on popular rural sentiment, he accused the president of selling off Madagascar’s ancestral land and claimed that the sale would make many farmers homeless. The Ravalomanana government countered that the Daewoo project would bring infrastructure investments and create hundreds of jobs for Malagasy farm workers growing maize on undeveloped land.

The feud between the two rivals had been brewing since Mr Rajoelina’s election in December 2007, when he defeated TIM’s mayoral candidate. Mr Ravalomanana had also become increasingly autocratic, stifling the opposition and amending the constitution to permit a third presidential term.

But the crisis intensified when the president closed down Mr Rajoelina’s popular television station and street demonstrations broke out throughout the capital. Soon it became clear that the army was backing Mr Rajoelina. On March 17th 2009 Mr Ravalomanana resigned from the presidency and fled to South Africa. The international community branded the power grab a coup and cut off all but humanitarian aid. To this day, it does not recognise Mr Rajoelina’s government.

Right after the power grab, the Rajoelina administration, also known as the Haute Autorite de la Transition (HAT, or high transitional authority), began arresting and harassing TIM leaders. “It was the law of the jungle,” Mr Randrianjatovo recalls. “We were trying to organise a rally when soldiers stopped our car. They found nothing, apart from pictures and posters of Ravalomanana, but they accused us of distribution of arms and money. One of the generals slapped me in the face and then they put us all in jail. One of the judges demanded 3m Ariary ($1,300) in bribes in exchange for our freedom.”

In August 2009 the Southern African Development Community (SADC) sat the two rivals down with two other former Malagasy presidents. They signed an agreement to form an inclusive, transitional government that would rule for up to 15 months, until November 2010, by which time elections would be held. Mr Rajoelina formed a transitional government but it was not very inclusive: only two of the 31 ministers were opposition members. SADC rejected the new government.

Negotiations stalled until March 2011, when a roadmap to elections was drafted under SADC’s watch and finalised in September 2011. This time Mr Rajoelina stuck more closely to the compact. By the end of 2011 he had appointed a neutral prime minister, Jean Omer Beriziky, assembled a 35-person cabinet with 12 opposition members and formed a legislature, in accordance with the roadmap’s recommendations. By April 2012 Mr Rajoelina had convened an electoral commission and passed an amnesty bill.

But the new legislature did not live up to its promise, Mr Randrianjatovo explains. “We thought that if we worked with the Rajoelina people, we would be able to implement the roadmap faster. The HAT people decided on the composition of the congress and took care [that] they are in the majority. Every time we bring up a question, they avoid answering and then we are outvoted.”

Mr Rajoelina has not softened his resistance to Mr Ravalomanana either, refusing to allow him to return to Madagascar and excluding him from the amnesty process. He remains determined to prevent Mr Ravalomanana from running in the next elections, contrary to the roadmap’s guidelines.

Elections have been scheduled for May 2013, but political analyst Juvence Ramasy is doubtful that they will take place. “Rajoelina has the power,” Mr Ramasy says. “Why would he hold elections?”

Elections are not the only problem, Mr Ramasy says. The Malagasy political parties focus on charismatic leaders rather than programmes, and opposition parties are always very weak. “Everyone wants to be in power, so after every power struggle, these politicians run over to the winner. After Ratsiraka was exiled by Ravalomanana, his party, Arema, ceased to exist. TIM has weakened also,” he says.

While Messrs Ravalomanana and Rajoelina do not differ in their political behaviour, Mr Ramasy does see a difference in their policies. “Ravalomanana wrote the Madagascar Action Plan—a program for economic development—after he was elected,” Mr Ramasy says. “The HAT hasn’t come up with any policy. The country has been stuck; there is no progress. The government builds new hospitals just to skim money off the top. The businesses of Rajoelina’s supporters are flourishing.”

Mr Randrianjatovo still looks to the foreign community to help Madagascar out of the crisis. “SADC should send people with Ravalomanana to protect him, so he can come back without being arrested,” he says. “The May 2013 elections will be meaningless without Mr Ravalomanana’s participation. These elections are our last hope. If they don’t succeed, fighting might break out after all. If SADC doesn’t succeed, Madagascar could turn into another Somalia. We’ll end up being a divided nation.”