Following IMF directives, President Joyce Banda reaps international praise, but poverty and protests persist

by Elliot Ross

The historian Dame Margery Perham was a major architect of the British colonial technique of indirect rule. “The great gap between the culture of rulers and ruled” was “the basic difficulty” with this method, she wrote. “People do not understand what we want them to do … or, if they understand, do not want to do it.”

The solution, according to Dame Margery, was “to instruct the leaders of the people in the objects of our policy, in the hope that they will, by their natural authority, at once diffuse the instruction and exact the necessary obedience.”

Christine Lagarde, the International Monetary fund’s (IMF) boss, may have felt something resembling Dame Margery’s frustration when she visited Malawi in January 2013 to review the institution’s structural adjustment programme. Malawi’s president, Joyce Banda, is more or less compliant with the urgings of western technocrats such as Lagarde, but the people Banda must try to rule are not impressed.

After years of being frozen out by her predecessor, Bingu wa Mutharika, Banda has restored the IMF to the top table of Malawian policymaking. At the fund’s behest, she has pushed through a sweeping programme of reforms, principally a massive 50% devaluation of its currency in May 2012 and the removal of major subsidies on fuel and other commodities, all in the name of attracting foreign investment. The immediate prize was a three-year loan of $157m. The IMF had withheld these funds from the recalcitrant Mutharika, along with an $80m credit facility. But as a reward for Banda’s currency devaluation, it restored them in June 2012.

The economy has not responded well. Bloomberg recently reported that the kwacha is now the worst-performing currency in Africa. A Malawian research organisation, the Centre for Social Concern, puts the rise in the cost of living for the average low-income urban family at 20% in 2012. Inflation is above 30%; food shortages are spreading; and the cost of fuel and other commodities has been rocketing since the devaluation.

Last November, the cost of petrol rose from 539 kwacha ($1.78) a litre to 606 kwacha ($2). Another hike in early February saw it rise further to 704.30 kwacha ($1.71). Two years ago, in February 2011, an increase from 256 kwacha ($1.72) to 290 kwacha ($1.95) was considered unsustainable.

Malawians reacted to the latest fare hikes by staging public protests in January, and then again in February. Civil servants and teachers went on strike, demanding a 67% pay rise. After two weeks without lessons, the city’s primary school children organised their own march through Blantyre in support of their teachers. They smashed windows at a school named after Joyce Banda and sat in the road blocking traffic before tear gas dispersed them. The strike was broken only when government acceded to a 61% salary increase for the lowest-paid civil servants, saying they would find the money from somewhere.

“The IMF is in panic mode,” says Professor Thandika Mkandawire, a development economist at the London School of Economics. “The social consequences of the policies are dire. The IMF is blaming this on poor implementation of social measures, whatever that means.”

Lagarde acknowledges that the reforms have not gone according to plan. Nonetheless, during her visit to Lilongwe, she ordered Banda to persevere with the IMF agenda. Lagarde left Malawi with a statement offering “congratulations” to Joyce Banda for her “bold” economic policies, and urging her to “stay the course”. Demonstrators in Blantyre, Lilongwe and Mzuzu took to the streets. They sang slogans insisting Lagarde is unwelcome in Malawi and accused the president of selling out the country to the IMF. In its latest review, published in late February, the IMF announced a new $20m loan, while noting nervously the “growing public outcry over falling living standards”.

Banda is a compelling and contradictory figure. Africa’s second female head of state, she is leading her country at a particularly puzzling historical conjuncture. If she is not careful she may not last long in State House. It was in the very first month of her presidency that Banda made the decision that will surely define her tenure: rushing through a devaluation of the kwacha that saw it drop 50% against the dollar. It looked like a bold move at the time. To many observers the devaluation seemed the only plausible option to engineer a rapprochement with an international community that had grown weary of the irascible Mutharika and had withdrawn budget support.

But his sudden death in April 2012 was followed by a brief but highly charged stand-off, which yielded one of the most dizzying political turnarounds in modern southern African political history: the ascension of Banda, more than a year after Mutharika had ejected her from the Lilongwe political machine. When she formed her own political movement, the People’s Party, members were so few in number that their bright orange uniforms signalled an optimism verging on the hare-brained.

There are three questions worth asking at this intriguing moment. The first two concern the balance of Malawi’s electoral calculus and future economic reforms in the developing world. In plain terms: will Joyce Banda lose the election in 2014 if she follows through with IMF demands? What would this defeat mean for the way global economic institutions go about their business in the Third World?

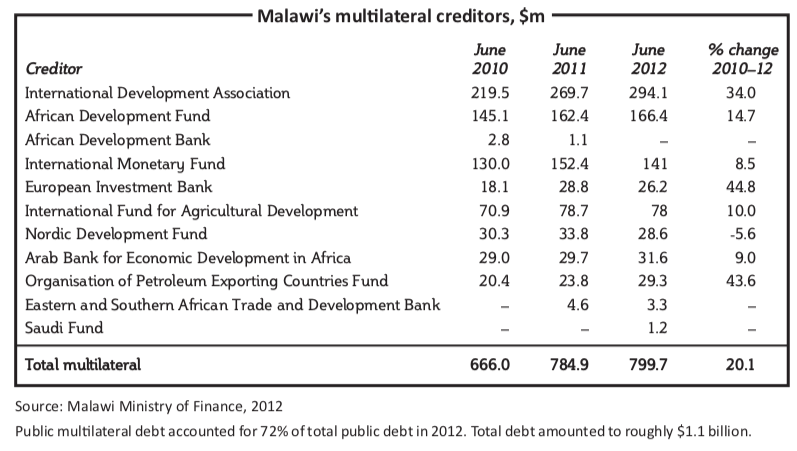

The third question relates to the broader historical and economic currents that underlie the current Malawian situation. In particular, how is it that for just $157m, the Bretton Woods institutions can still dictate the monetary policy of a country such as Malawi in 2013?

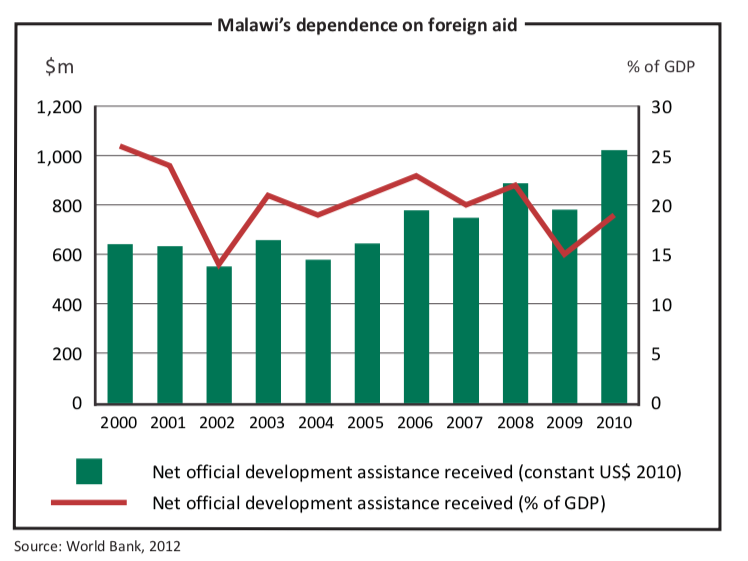

The question of Malawi’s reliance on global financial institutions has not always been so perplexing. This dependence, however, ought to have declined, with China established as a major partner and international energy companies hovering for big resource contracts. The government continues to draw 40% of its budget from foreign donors. The IMF’s own figures estimate that nearly half of the country’s 15 million population live on less than $1 per day.

The Malawian economy has been heavily dependent for many years on its agricultural sector, as the continent’s largest exporter of burley tobacco. Last year, the International Tobacco Growers Association estimated that the crop accounted for 70% of Malawi’s foreign exchange earnings, and 15% of total GDP.

The country’s much-vaunted relationship with China, fostered over the past decade, is not sufficient to allow Malawi to ignore IMF directives. With Chinese financial and technical support, a grand new parliament building has sprung up in Lilongwe; a national stadium is on the way. While Joyce Banda does not imitate her predecessor by wearing a Chinese-collared shirt, relations appear to remain very cordial.

But whatever China is getting from Malawi, Malawi is not gaining much in the way of hard financial clout. In his second term, Mutharika ruled as though the only international relationship Malawi needed was with China. Western donors withdrew. Ordinary Malawians soon found themselves suffering a nationwide shortage of foreign exchange, fuel and medical supplies.

What about Malawi’s natural resources? The country seems to have discovered considerable oil beneath Lake Malawi, creating tensions with neighbouring Tanzania, which also borders the lake. This find has come at precisely the right moment, just when economists around the world were scratching their heads over how Malawi’s economy will function when the world tobacco market finally peters out. Still, it will probably be a number of years before the Malawian treasury takes in its first petro-kwacha.

Until then, Banda has to govern with whatever funds are available to her. In September 2012 she spoke to a private audience at the plush Waldorf Astoria hotel in Manhattan. One of the first things she did after taking office was to examine the national finances as Mutharika had left them. These, she said, were comparable to the numbers one might expect to find in the current account of an ordinary private individual in the United States.

It is a striking claim, and one that certainly helps explain why Banda was willing to take such a sizeable political gamble to get hold of the IMF’s $157m. But it also gets to the heart of one of the defining contradictions of Mrs Banda’s presidential style: she is a gender-rights activist who often sounds like a saleswoman. She attempts to perform simultaneously both these roles on the international stage.

She has learned to speak in the public relations-style language of the business school circuit. She sells Malawi as an attractive investment opportunity, a place to do business. This is no incidental concern, since encouraging foreign direct investment is the fundamental objective of the IMF reforms. Yet in the very same western capitals Banda is feted as a pioneer for the rural poor and women’s rights. She convinces most when she offers Malawi as a sob story.

The two lenses through which Banda depicts Malawi — near basket case on the one hand, confident emerging market on the other — simply do not make sense when offered together. Ordinary Malawians are telling her that they have had enough of “donor-fearing” politics.