Despite becoming a beneficiary of Malawi’s subsided fertiliser scheme three years ago, Clement Kalonga of Nsanje district in southern Malawi has never been food secure.

He is just one of Malawi’s subsistence farmers who has found the process of buying subsidised farm inputs chaotic and exhausting. “It’s been one issue after the other,” he wearily tells Africa in Fact. “Some years, I’ve had a problem with buying because the designated fertiliser stores were always full of people… In others, like last year, the fertiliser was not available on time, and when it came, the shop owners prioritised selling to vendors rather than those of us on government subsidies.”

Malawi’s subsistence farmers have long been the backbone of the nation’s agricultural sector, providing food security for countless families across the country. However, despite government efforts to support these farmers through subsidies, many like Kalonga continue to face challenges that prevent them from reaping the full benefits of these programmes.

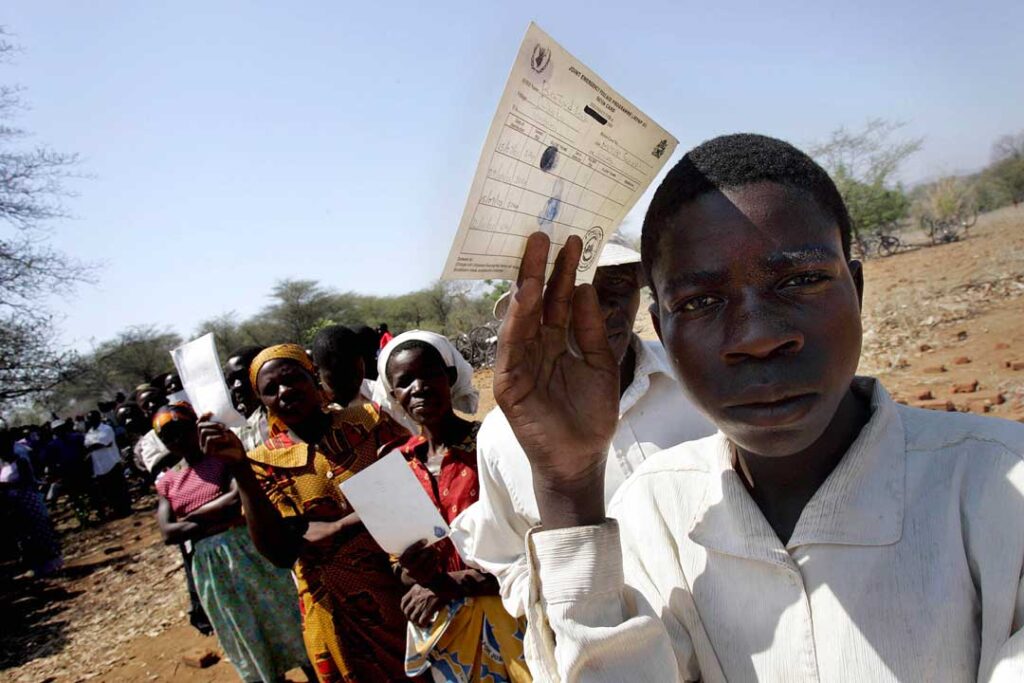

The initiative he is referring to is the Affordable Input Programme (AIP), which was introduced in 2020 to provide farmers with access to subsidised fertilisers and seeds. While the programme has the potential to significantly improve farmers’ livelihoods, it has been plagued by various issues, including delays in coupon distribution, irregular fertiliser availability, and bureaucratic complexities.

Last year, Kalonga and farmers like him fell foul of delays in the distribution of AIP coupons. These coupons, which provide access to subsidised fertilisers and seeds, often arrive too late in the planting season to be applied. The traditional maize farming season in Malawi typically begins in November and ends in March/April, coinciding with the rainy season. Farmers need timely access to coupons to purchase fertilisers and enhance their crop yields.

Added to this was the non-availability of fertiliser at designated traders who have an agreement with the government to sell subsidised fertilisers in exchange for the coupons. Traders instead prioritised customers who bought fertiliser for cash upfront for the equivalent of $68 per 50 kg bag rather than those customers with coupons, which enabled them to buy the fertiliser for the subsidised price of $14.

Mathias Chilumba, the chairperson for the Area Development Committee (ADC) in Traditional Authority Malemia in Nsanje, says many people under his jurisdiction are still food insecure despite receiving the AIP coupons.

He corroborates Kalonga’s experience in that people in his community also borrowed money from loan sharks to pay for fertiliser in advance (from government extension workers who went around the villages to collect money from AIP beneficiaries), hoping they would be able to repay their debt with a good harvest. However, these farmers were now in trouble, he said, because they had not harvested enough to get out of debt.

“It seems the AIP woes will never end,” Chilumba told Africa in Fact. “It’s not helping us rural people as it’s claimed to do. The government needs to do its homework with this programme so farmers have everything in place before the first rains. Otherwise, it’s no benefit to us.”

Overall, the 2022/23 AIP programme faced numerous issues with procurement, distribution, sales, and access to inputs, leading to inefficiencies in supply chain management and delivery.

Both the Anti-Corruption Bureau (ACB) and the Office of the Ombudsman (a public body established under the Malawi Constitution to investigate all cases where it is alleged that a person has suffered injustice) have agreed that the 2022/23 programme had many challenges.

This was despite the introduction of a mobile vending system over that period to reduce the distance beneficiaries had to travel to access inputs and eliminate the waiting period for them. An ACB report noted that the mobile vending system was not properly executed in some areas because there were no proper arrangements to announce when the vehicle would arrive.

Questions have also been raised about the efficacy of the programme given that many AIP beneficiaries still need additional help from the government’s relief food aid during lean times, with some critics suggesting that overall food security would be better served by allocating subsidies to the farmers who produced the highest yields, while those who were not producing more due to AIP assistance should rather seek help from other programmes.

Suggestions of how the scheme can be made more efficient also included the following:

- Coupons should be distributed well in advance of the planting season, ideally starting in September. This would give farmers ample time to prepare for the planting season and to buy fertilisers and seeds when they were most needed;

- The government must strengthen its partnership with designated traders, with agreements between them strictly enforced and penalties imposed on traders who prioritise cash buyers over coupon holders. Adequate supply chain management should also be established to improve the distribution of the fertiliser;

- The government must ensure better transparency and accountability over the AIP, actively involving stakeholders in the AIP planning and decision-making process;

- The government must revise the criteria for participating in the AIP to ensure the programme assists farmers who genuinely need help.

William Chadza, the executive director of Mwapata Institute, an independent agricultural think tank, agrees the programme needs to be better targeted, telling Africa in Fact: “There is a need to revisit [how the] AIP targets recipients so that it translates into productive farming. Non-productive farmers should go to other social protection programmes. This would help in avoiding the duplication of beneficiaries.” Chadza noted, however, that the AIP has not been successful due to politics. “Politicians feel if this is done in a proper manner, they might lose votes,” he said.

The Malawi Vulnerability Assessment Committee (MVAC) report released in August this year indicated that an estimated 4.4 million Malawians were likely to face hunger in the 2023/24 consumption period. This number represents 22% of the country’s population of 19.6 million.

Earlier this year, Ministry of Agriculture Principal Secretary Dixie Kampani told the media that the 2023 AIP programme activities would begin in October, with implementation plans at an advanced stage. At the time of writing, in mid-September, the ministry announced that the AIP programme would target between 1.3 million – 1.5 million households over 2023–2024, a sizeable reduction from last year. The number of beneficiaries would be determined by the final price of the subsidised inputs.

While the AIP has the potential to significantly benefit Malawi’s subsistence farmers, its current challenges hinder its effectiveness. By addressing issues related to coupon distribution, fertiliser availability, advance payments, and programme governance, the government can ensure that AIP contributes to improved food security and poverty reduction in the country. It is essential that these challenges are recognised and addressed to provide better support to the backbone of Malawi’s agricultural sector: its subsistence farmers.

Josephine Chinele is multi-award-winning international journalist. She has worked as a news, features and investigative journalist for newspapers, radio and television platforms in Malawi, Tanzania and South Africa. Josephine has also been awarded several prestigious journalism fellowships in the area of HIV and AIDS, health and human rights among others. She is also a biomedical HIV prevention advocate.