Many hoped that Joyce Banda would unshackle Malawi’s press when she became president in April 2012

by Keith Somerville

When Malawi’s former president, Bingu wa Mutharika, collapsed on April 5th 2012 at his official residence, the press went into a frenzy, expressing itself in ways it had not been allowed to for years.

For 48 hours, radio stations and newspapers reported conflicting stories of Mr Mutharika’s condition, some even claiming that he was undergoing treatment at a South African hospital. A major power struggle unfolded between Mr Mutharika’s cronies, who plotted to install his brother Peter as president, and the vice-president, Joyce Banda, who had been sidelined earlier for criticising Mr Mutharika’s autocratic ways as well as his violations of free speech and human rights.

In the uncertainty and confusion following the news of Mr Mutharika’s heart attack, there was no serious attempt to stifle discussion or reporting, however wild and inaccurate it sometimes was. During this brief interregnum, the Malawian press overflowed with opinions in favour of a constitutional process. This outpouring may have contributed to the decision by the army to uphold the constitution and ensure Mrs Banda’s inauguration as president. On April 7th 2012, Mrs Banda finally took the presidential oath—just hours after the state-run Malawian Broadcasting Corporation finally announced that Mr Mutharika was dead.

In her pre- inauguration statements and since assuming office Mrs Banda has expressed a commitment to respect human rights. Malawians, especially the media, have been watching closely to see if these statements result in any loosening of the government’s hold on the press.

Some things changed fairly quickly. In one of her first acts, Mrs Banda reversed the amendment to section 46 of the penal code that Mr Mutharika had implemented in February 2011. The legislature, packed with members of Mr Mutharika’s Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), had adopted this law without serious consultation with the media. It gave the information minister the power to prohibit publications he believed were contrary to the public interest, an arbitrary way to hamstring the press.

Despite this step forward to unshackling the press, there have also been some worrying trends under Mrs Banda. Speaking in Blantyre, Malawi’s commercial capital, in late April 2012, Anthony Kisunda, chairman of Malawi’s branch of the Media Institute of Southern Africa (MISA), said that he was concerned that many DPP leaders who had openly threatened journalists and freedom of the press under Mrs Banda’s predecessor were now part of the new government.

Five months later, in October 2012, MISA put out an alert concerning another proposed law that would impose stricter regulations on internet communications and force editors of online publications to register their personal details with the state.

“The signal we are getting here is of a government that wants to restrict media freedom and freedom of expression…a government that may have grown deeply suspicious of its citizens’ activities online,” said Levi Kabwato, MISA’s media freedom specialist.

The attitude of Mrs Banda’s government was manifested in October last year, when Justice Mponda, a journalist for the news website Malawi Voice, was arrested on charges of insulting the president, criminal libel and publishing false information. He had reported that the Malawian government had given the Tanzanian ambassador 48 hours to leave the country. The government denied this.

The authorities released Mr Mponda on bail and later converted his charges to a single one: publishing false news likely to cause fear and alarm among people. But much of the equipment that was confiscated by police was returned only two months later. Mr Mponda’s trial dragged on while the state prosecutor was granted several adjournments. Finally, he was acquitted in February 2013 due to lack of evidence after state witnesses failed to show up five times.

Overall, it appears that Malawi’s press remains as muffled as ever. Mr Mponda’s arrest was made possible by out-dated laws inherited from the immediate post-independence era, which still govern much of the state’s relationship with the media. “Today some of those laws still exist and they are still being used as a tool to silence critics,“ Mabvuto Banda (unrelated to Mrs Banda), a Malawian correspondent for Reuters, told Africa in Fact.

“Banda, just like any other president before her, is using underhand tactics to bully media houses that are perceived to be against her by threatening loss of advertising revenue or publicly castigating newspapers,” Mr Banda said.

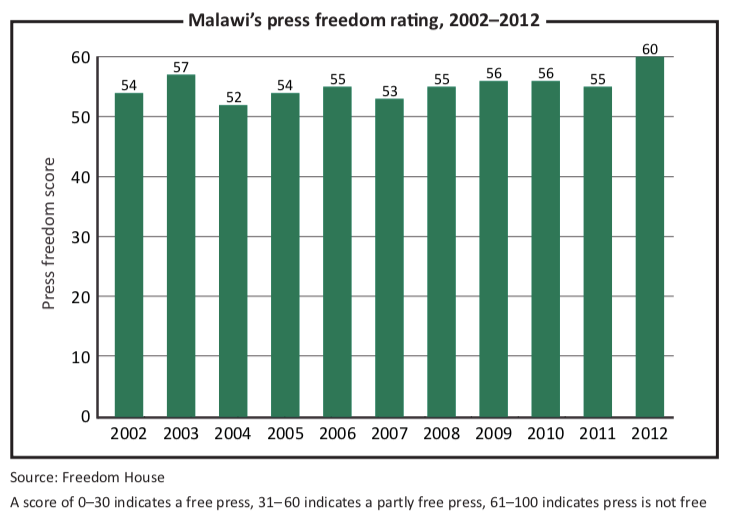

Curbing press freedom and stifling dissent is almost a presidential prerogative in Malawi. It began with the tiny country’s first president after independence in 1966, Hastings Kamuzu Banda (unrelated to Mrs Banda). He manipulated the DPP’s youth wing to intimidate and attack his opponents. Mr Mutharika continued this tradition. Despite shining as an efficient economic manager in his first term, the economic bloom came to an end after he was enthusiastically re-elected in 2009. As criticism of Mr Mutharika’s economic policies increased and evidence of corruption mounted so did his intolerance of the press. As a result, Malawi fell 67 places to 146 of 179 countries listed in the Reporters Without Borders Press Freedom Index for 2011–12.

This watchdog’s latest index, released in January 2013, now shows Malawi at 75 out of 179 countries, up 71 places. Many believe this remarkable rise in the media index is a reflection of international praise for Mrs Banda, who is credited with implementing a new economic policy backed by the International Monetary Fund, and not a true picture of what is actually happening in the country.

Journalists in Malawi still have to jump hurdles such as government harassment and other bullying tactics. They must also sidestep bureaucratic blocking of public information. A 2012 MISA report on government secrecy in Malawi found that “government ministries and departments are still not open and do not freely give out information in Malawi,” and only three of eight sampled ministries responded to written requests for information.

“This encourages speculation because it is so hard for any journalist in Malawi to verify and authenticate their stories before publishing. This to a large extent affects the quality of our stories,” Mr Banda said.

Media ownership is government connections own private broadcast and print media in Malawi. The Malawi Broadcasting Corporation (MBC) dominates radio and television (only 2% of Malawians are able to receive alternative satellite channels and MBC has the only free- to-air television station) and is the voice of the government. The only real competitor for the MBC is Capital Radio, a private commercial station which was hated by the Mutharika government, leading to frequent arrests of journalists.

Another commercial station, Joy Radio, is owned by former president Bakili Muluzi, whose son Atupele is part of Joyce Banda’s new cabinet.

The print sector has heavy political involvement too. The Nation company is owned by veteran politician Aleke Banda and it publishes The Nation, Nation Online, Weekend Nation, Nation on Sunday, Fuko and their associated websites. Blantyre Newspapers Limited (BNL) is a subsidiary of Blantyre Printing & Publishing Company Ltd., which belonged to the late president, Kamazu Banda. It publishes The Daily Times, Malawi News and Sunday Times and is close to the Malawi Congress Party of John Tembo.

Among other publications, The Mirror is owned by Brown Mpinganjira, who was John Tembo’s running mate in the 2009 elections, while The Enquirer is owned by an official of the United Democratic Front Party, Lucious Chikuni.

Such a high level of politicised ownership can hardly be healthy for democracy, even if the ownership is transparent.

The list of challenges to press freedom in Malawi is long. Mr Mutharika’s death created an opportunity for rescuing the media and revitalising democracy. But if Mrs Banda is to make a difference to press freedom, she will have to do far more than she has thus far.