Misrule and misused foreign aid paved the way for the jihadist war

by Isaline Bergamaschi

While French and now African troops battle Islamist insurgents in Mali’s north, the government in the southern capital of Bamako plans to hold nationwide elections in July 2013. Will this latest stumble towards democracy succeed? Will it solve the problems that led to this impoverished country’s crisis — poor governance and more specifically, the squandering of its foreign aid?

Since independence from France in 1960, Mali has suffered droughts, rebellions, two coups and 23 years of military dictatorship. After a free and fair election in 1992 and 10 years of democratic transition, the military deposed the president in a third coup in March 2012. A month later, Tuareg rebels seized control of northern Mali.

Focusing on Mali’s “Islamist terrorist threat” overlooks the complex roots of Mali’s crisis. For decades the Tuareg, a traditionally nomadic, but increasingly sedentary, group have been seeking greater autonomy for their northern homeland that is scarred by chronic drought and now facing major environmental devastation.

Their main grievances, as with other disputes throughout Africa, are tied to resources and land. The Tuareg want a voice in Mali’s politics and economy.

Mali’s governments have countered with repression, decentralisation, demobilisation and development programmes. But these programmes have either failed or benefited only a few local notables and “big men”, according to Morten Bøås, a senior researcher at the University of Oslo, Norway. After Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi’s downfall in 2011, insurgents joined forces with Islamist movements and organised kidnapping, smuggling and drug networks operating in the Sahel. After the March 2012 military coup, they succeeded in taking control of northern Mali and were marching towards Bamako when the French troops arrived.

The military overthrow of President Amadou Toumani Touré, known as ATT, was quick and nearly bloodless. It succeeded largely because ATT was unpopular and corrupt and did little to improve the lot of Mali’s 14.5 million people, whose per capita income in 2012 was $610, according to the World Bank. Critics had accused ATT’s government of networking with drug traffickers and selling off vast swathes of fertile land to international firms at discount prices.

ATT had accomplished this through his politics of “consensus”, a coalition of all political parties and some civil society groups that in effect neutralised any opposition. This alliance not only intensified corruption but, even worse, it hindered efficient decision-making. Most candidates running for president in elections that had been scheduled (before the coup) for April 2012 had worked in ATT’s government, thus offering little chance for real turnover. The military takeover succeeded because party politics was deemed opportunistic and completely discredited.

Over the past few decades, this history of failed governance has left Mali poor and heavily dependent on foreign aid. Structural adjustment programmes in the late 1980s further weakened the state’s public services, particularly to the poor. Many civil servants and public enterprise employees were retrenched. In education, religious groups filled the vacuum created by the government. International donors also tried to help, but prioritised primary education at the expense of Mali’s only university. The nation’s youth are poorly trained, and while national unemployment was at 9.6% in 2011, the rate was about 15.4% for 15–39 year-olds, according to the African Development Bank.

Some conditions attached to aid have further destabilised the country. Since 2000, the World Bank has pressured the government to privatise the Compagnie Malienne de Développement des Textiles, responsible for supervising cotton production (This highly strategic economic sector provides income for one-fourth of Mali’s population). Mali’s cotton sector lacked the capacity to implement the World Bank’s programme. The government’s own resistance to the privatisation and reform agenda have disrupted the production chain and, consequently, producers in the country’s south have lost income and trust in the government.

As of 2009, Nordic donors and Canadian diplomats have insisted on modernising the family code and giving more rights to women, leading to a battle between secular leaders and thousands of Malians mobilised by popular imams such as Mahamoud Dicko, president of the Islamic High Council of Mali.

Equally problematic was former French President Nicholas Sarkozy’s insistence that the Malian government sign immigration agreements to accelerate the deportation of illegal Malians living in France. The government refused for economic reasons: in the south-western region of Kayes, whole villages survive on remittances sent by relatives in France.

The three-pronged strategy adopted by donors — privatising cotton production, reforming the family code and tightening immigration — was deeply unpopular, succeeding in widening the gap between the ruling elite and the electorate.

Aid agencies and the government “chew and digest” every public policy together with little regard for grassroots realities and regional dynamics, said a representative of the Agence Française de Développement, France’s official aid financing institution. In addition, donors turned a blind eye to the regime’s delinquency and maintained Mali’s status of “donor darling”, a privileged recipient of foreign aid.

Budget support, that is aid delivered directly to the treasury, grew and grew. It rose from 12% to 42% of Mali’s total aid since 1999, accounting for almost one quarter of Mali’s public expenses in 2009, according to a joint evaluation by the EU, Belgium and Canada.

This aid stream powered ATT’s politics of “consensus”. Corruption scandals swamped programmes ranging from the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria to the US anti-terrorism efforts in the Sahel. Suspicion that high-ranking generals had “eaten” this money — a popular expression — was a central motive of the putschists. Donors’ political dialogue with the government deteriorated into a purely technocratic exercise. When they tried to engage with the private sector, funders chose to favour an urban, donor-oriented, professional civil society not that different from the government.

Aid in northern Mali helped finance a policy of decentralisation, which was adopted by the government in the 1990s and aimed at co-opting the Tuareg threat, according to Jennifer C. Seely of the University of Denver, who has written extensively on African politics. It improved access to basic social and health services such as clean water or vaccines.

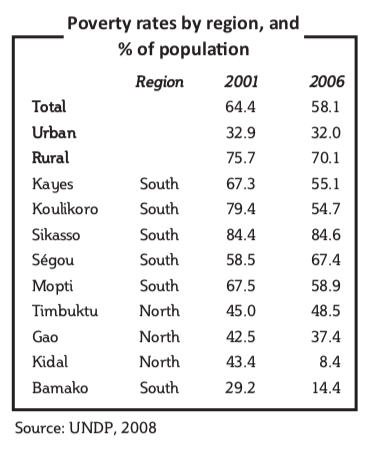

But in the past decade international donors have reduced their activity in northern Mali. Their lessened presence began when national surveys showed that poverty in the regions of Gao, Kidal and Timbuktu was below national levels. Also, as incidents of drug and cigarette trafficking and the kidnapping of westerners increased, donors became too scared to visit northern Mali, or simply could not get there. Crime made it more expensive to build new roads or fix the old ones. The few NGOs, churches and other charitable associations that have ventured there run poorly funded projects lacking coherent vision or planning.

Youna Touré, former coordinator of a European project in Gao, and many others disagree that funds were lacking in northern Mali. Instead, money was poorly used. First, the central government in Bamako limited its allocation to the north. Then, at the local level, fraudulent deals privileged projects badly designed by public bodies and private firms at the expense of the intended recipients, particularly women and youth. After the March 2007 Kidal Forum, a meeting of international donors and the Malian government, a Malian economist alleged that ATT was not committed to development projects in northern Mali and predicted that the country would erupt in five years’ time. From 2009 to 2012, the president’s injection of millions of euros into Mali’s northern cities was a muddled and desperate attempt to buy off Tuareg leaders and ease tensions at a superficial level.

The French armed intervention succeeded in chasing armed groups out of northern cities in January, February and March 2013. In its aftermath, interim authorities adopted a roadmap for a transition to democratic governance. Development assistance has resumed and the international community has pledged considerable funds to Mali.

Here are some recommendations on how to spend this money more effectively than in the past.

First, the three main branches of international aid — military, security and humanitarian — which have so far been used to deal with the crisis are not enough to tackle the conflict’s root causes and pave the way for the post-conflict scenario. Donors need to adopt a long-term development perspective. Their projects should encourage growth by assessing economic potential and identifying alternative activities to trafficking, smuggling and Islamism. One option could be co-ordinated support to the cattle, meat, milk and leather industries, all essential to livelihoods in Mali’s northern regions.

Second, donors and governments should think of Mali as one nation and not divide it into north and south. Mali’s crisis is multi-dimensional and not limited to its Sahelian parts. If future aid is distributed disproportionately to one area, resentments could rise. Aid agencies can help create the egalitarian conditions under which all Malians feel included, better protected by their state and more willing to confront their “big men” countrywide. To do so, aid agencies must not only listen to the central government, but also engage with citizens, elected leaders and social groups at the regional level.

Finally, donors should critically assess the priorities and implementation of past aid efforts. They must not approach governance through standardised, one-size-fits-all approaches, but rather through methods that promote inclusive politics and economic growth. Social services should focus on quality and not only coverage. Donor procedures should be amended so that disbursements are relevant to recipients. Monitoring and follow-up should concentrate on enhancing control and accountability while diminishing corruption.