South African industry

To revive its manufacturing sector, Africa’s largest economy needs to bridge the gap between labour, industry and government

Africa, so the story goes, makes nothing except holes in the ground. And while extractive industries drive economies across the continent, they do not produce the sort of employment figures that make for sustainable growth.

In South Africa, the continent’s largest and most diversified economy, a yawning lacuna between industry, labour and government is not just curbing manufacturing but promises to swallow the entire nation.

This chasm was plainly in evidence during a forum held last November by Johannesburg-based consultancy outfit Frontier Advisory, operated by Martyn Davies, a leading analyst and former Stellenbosch University academic. Held about once a month, these forums often involve people who would not ordinarily find themselves in the same room. This was certainly the case with “The Future of Manufacturing in South Africa”. The irony is that there is no future for manufacturing in South Africa if representatives from industry, labour and government are not in the same physical space as often as possible.

The preamble printed on the programme did not offer much solace: “Despite having the strongest manufacturing base in the region and strong demand for manufactured goods in African economies, South Africa’s manufacturing sector continues to underperform. Recent strife between labour and investors in the country’s manufacturing sector has only served to highlight how divergent the future vision for manufacturing is in South Africa.

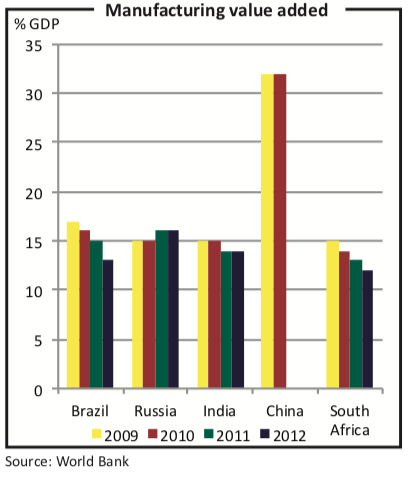

According to the World Bank, South Africa’s manufacturing value add as a percentage is now down to 12% of GDP—the lowest amongst all the BRICS countries.

What is to be done to fix manufacturing in South Africa? What are the views of industry, government

and labour and how can these be reconciled?”

During his introduction, Mr Davies made his views plain: manufacturing in South Africa is in free fall. In 1994, the sector contributed between 23% and 24% of GDP, a number which has now plunged by half, according to Mr Davies. “Hence,” he noted drily, “the enormous unemployment figures in this country.”

Alongside Mr Davies sat Mike Whitfield, the managing director of Nissan South Africa. To his left sat Karthi Pillay, director of IT, Risk and Control at Deloitte, followed by Pat- rick Craven, national spokesman for the Congress of South African Trade Unions (Cosatu). Coenraad Bezuidenhout, of the industry lobbying group Manufacturing Circle, and Bill Scurr, executive director of the Southern African Stainless Steel Development Association, rounded out the panel.

This coterie were all ostensibly invested in stemming the fall and spurring the rise of local manufacturing. But as you might imagine, they drink different flavours of the economy wonk’s Kool-Aid. How to stop the plunge? While each member of the panel had a subtly different outlook, some views overlapped.

For his part, Nissan’s Mr Whitfield wanted us to remember that nowhere in the world do car manufacturers work without co-operation and incentives from government, such as tariff protection, tax breaks and subsidies for building factories. With African plants in Egypt, Morocco, South Africa and, shortly, Nigeria, Nissan’s modus operandi is always based on receiving a helping hand. Mr Whitfield made the point that the size of the incentives guide where and when a car manufacturer sets up shop.

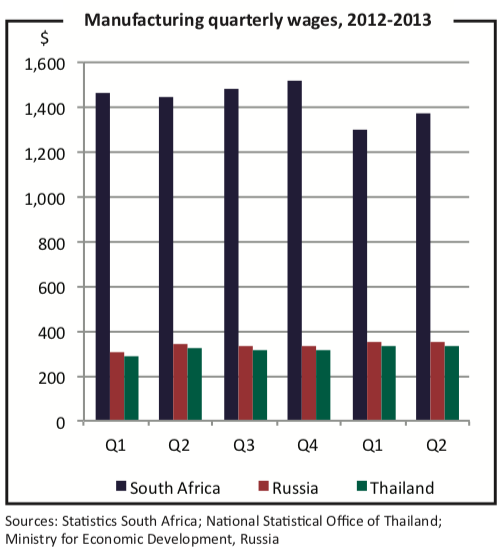

“It now costs 20% more in South Africa than it does in, say, Thailand,” he said. Warily, he noted that the 20% uptick had much to do with labour costs. Seven car manufacturers operate in South Africa, and all seven had just been slammed by almost eight weeks of industrial action led by the National Union of Metalworkers of South Africa (NUMSA). The strikes led to an agreement that saw workers granted a 10% wage increase in 2013, and 8% in 2014 and 2015. This led BMW to pull the plug on plans for an expansion of its manufacturing programme in South Africa. In total the strike cost the sector almost 20 billion rand ($1.8 billion).

Such carnage resonates across the entire sector. Mr Pillay directed our attention to the just-published Deloitte 2013 Global Manufacturing Competitiveness Index, a yearly survey to determine how hundreds of leading international CEOs view the competitiveness of the manufacturing industry in 38 countries around the world.

Unsurprisingly, China ranked number one. Another four emerging economies were included in the top ten: India (4), Taiwan (6), Brazil (8) and Singapore (9). Five years from now, according to the survey, emerging economies will surge to the top three places, with India and Brazil following fast on China’s heels. South Africa? A grue- some 24 out of 38, followed by sundry crisis-hit European states, Saudi Arabia and the UAE. That is not company South Africa can afford to keep.

“This country employs 1.5m people in the manufacturing sector,” Mr Pillay said, by way of explanation. “And manufacturers struggle with a high-wage to low- productivity ratio.” Worker productivity is usually calculated by dividing total output by the number of workers or the number of hours worked. Labour yield has fallen from 7,297 rand ($675) to 4,924 rand ($456) a year since 1967, a decline of 32.5%. From a peak in 1993, labour productivity has plummeted by 41.2%, according to a 2013 report from Adcorp, a Johannesburg Stock Exchange-listed human capital management group.

Industry complaints about productivity generally focus on unions’ high wage demands and an abject lack of skilled or educated workers. However, productivity is not just a worker issue, but a management issue, argued Cosatu’s Mr Craven. “If your productivity is low, don’t the managers need to be held accountable?” he asked.

Mr Craven is not troubled by high wages. He pointed to Brazil’s vaunted “Lula moment” during the 2000s, when then-President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva raised basic wages, social grants and provided subsidies for small businesses. The Brazilian economy exploded, growing 7.5% in 2010, according to the World Bank. “And not,” said the union stalwart, “by underpaying workers.”

The state has a role to play in bridging gaps between industry and labour, Mr Craven said, but perhaps not the same role that the industry representatives on the panel had in mind. “We need a developmental approach,” he added. “Market forces alone are not going to fix this.”

Most of those gathered agreed that a weak rand—usually hyped as a salve for manufacturing—was not a silver bullet. Lowering the value of the currency, while helpful in the short term, was not going to fix the desultory structural issues that were destroying the economy and shedding jobs like so much dandruff.

The issue, Mr Davies suggested, was not that there were no ideas, but that those ideas were not being communicated between industry, labour and government. Mr Davies recalled post-unification Germany as an example of a country that success- fully bridged these gaps.

“Similar to South Africa,” he said, “in 1990 Germany was [a] newly united country, with its population living in…different stages of development. But the Germans were able to significantly integrate the East into the developed economy, drive employment figures up, and keep industry manufacturing high-end goods with skilled and educated employees earning a living wage…and while Europe dies around it, Germany thrives. Never mind the Lula moment, what about the Merkel moment?” he asked, referring to Angela Merkel, Germany’s long-term chancellor.

According to a 2001 study from the Brookings Institution, a think-tank based in Washington, DC, “from 1989 to 1992, GDP in the former German Democratic Republic (GDR) declined by roughly 30%, value added in industry by more than 60%, and employment by 35%. During the same period, unemployment rose from officially zero to more than 15%.” In short, Germany’s east was a backwater in 1992.

But by 2000 the former GDR’s GDP per capita had risen to 65.3% of the for- mer West Germany’s, thanks to a comprehensive programme of wealth transfers and industry-government collaboration. Berlin did everything in its power to ensure factories did not leave Germany; development was not an economic drain, but an economic engine. As the writers of the study argue, “The ultimate measure of the economic success of German reunification is no longer the introduction of a market economy, but rather the attainment of an efficient production pattern made possible by the union of the two regions.”

While Germany’s manufacturers can rely on an endless stream of highly educated, highly skilled workers entering the work force every year, South Africa’s cannot. As Mr Craven has noted, “Our education system is in a crisis and it sidelines 400,000 young people who do not proceed with their studies after writing exams every year. Today, 95% of the people who are unemployed have no tertiary education, 60% of the unemployed have no secondary education. As a result of this crisis, 68% of the unemployed have been unemployed for the past five years or have not worked in their lives.”

What can South Africa learn from the Germans? First, it can buck up employment by ensuring that the education system provides the jobs market with highly skilled, highly productive workers. Next, it can support industry at the research and development level. It can encourage factories to stay on shore with aggressive tariffs and foster an environment of innovation, where industry builds for an international market with an appetite for excellence. Last—and perhaps most important—it needs to create a culture of co-operation, where a win for labour is a win for industry is a win for government.