Kenya’s industrialisation

The east African country has failed to kick-start its manufacturing sector, but not for lack of trying

Nairobi’s industrial district is well laid out—or at least looks that way on a map. The district’s main thoroughfare, Enterprise Road, starts just outside the city’s Central Business District and runs for almost 15km. Alphabetically named roads branch off at regular intervals. Each of these ends in a broad cul-de-sac designed to allow lorries to turn easily. The main railway has branch lines terminating at every warehouse to expedite the off-loading of goods.

Off the map and on the ground, a very different picture emerges. The roads are choked with traffic, the sidewalks covered in litter. The railway tracks are overgrown with weeds, and car mechanics and metal forgers have taken over the cul-de-sacs.

This wide gap—between the efficiency imagined on the map and the cluttered chaos on the ground—is analogous to the gap that separates Kenya’s manufacturing plans from its actual progress towards becoming an industrialised country.

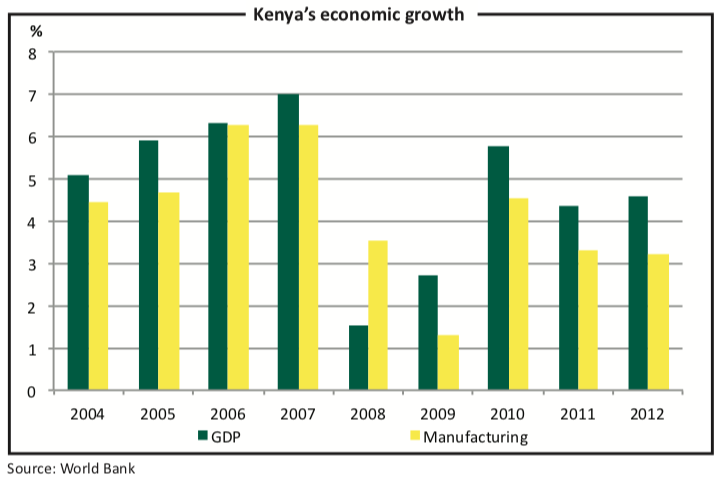

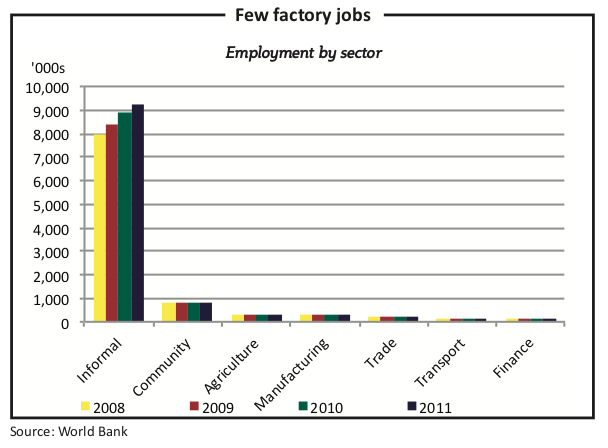

With a two-year hiccup provoked by election violence in 2008 and the global financial crisis, Kenya’s GDP has grown on average 5% annually since 2004, according to the World Bank. Industrial production, however, still languishes at 15% of GDP, with agriculture accounting for 24% and services for 61%, according to the Kenyan National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS).

A historical perspective helps to understand why industry lags. When Kenya gained independence from Britain in 1963 it inherited an industrial policy that aimed at substituting imports for locally manufactured products. Continuing this policy, the newly independent government under Jomo Kenyatta invited foreign manufacturers of locally-consumed products to set up in the country and to make these goods using locally-sourced raw materials.

The government protected these infant industries from competition through quantitative restrictions, import licensing, foreign exchange controls, high tariffs on competing imports and overvalued ex- change rates that made imports uncompetitive. The East African Community (EAC), an intergovernmental body Kenya set up with Uganda and Tanzania to create a common market, customs tariffs and other shared public services, also attracted foreign inves- tors.

This policy of import-substitution worked, for the most part. In the five years following independence, manufacturing value added increased 44%, led by the tex- tiles, food, beverages and tobacco sectors. Annual growth in manufacturing peaked between 1971 and 1973 at over 25%, according to the World Bank.

The downside, however, was that the protective policies were so effective that established foreign companies—such as chemical manufacturer Union Carbide and rubber producer Firestone—enjoyed near monopolies; and parastatals took over tradi- tional spheres such as utilities but also many aspects of manufacturing and distribution.

These private and government-owned monopolies did not permit the develop- ment of a competitive business model and contributed to massive inefficiencies in do- mestic industries. By 1980 this import-substitution strategy had run its course. Imports of consumer goods had declined and new industries could not be established to pro- duce local substitutes. In addition, the collapse of the EAC in 1977 reduced the regional market for Kenyan manufacturers.

Kenya did not participate actively in export, focusing instead on supplying domestic and regional markets, which traded in relatively weak local currencies. The country ran into repeated foreign exchange shortages and found it increasingly difficult to pay for crucial imports, such as petroleum.

Faced with these constraints, in 1980 Kenya became the second country—after Turkey—to sign a structural adjustment agreement with the World Bank. A $55m loan from the bank was conditional on the Kenyan government adopting more liberal trade and interest rate regimes, as well as a more outward-oriented industrial policy.

From 1982 into the 1990s, under pressure from donors, particularly the World Bank, Kenya began shifting import restrictions from quotas to tariffs, and decreasing tariff levels. In 1987, 40% of all importable items had quantitative quotas, but by July 1991, import licences were only used for health or security reasons.

In addition to opening up imports, Kenya introduced several programmes through the 1980s and 1990s designed to promote exports, such as the manufacturing- under-bond scheme in 1988, which allowed manufacturers producing for export to import equipment duty-free, as well as the creation in 1990 of manufacturer-friendly export processing zones.

Kenyan industry experienced a major shake-up during the structural adjustment period, particularly as a result of competition from cheaper imports. Many companies collapsed, including Kisumu Cotton Mills, the Pan Paper Mills, and other state- owned firms that had previously operated as monopolies.

The liberalisation of the market saw an influx of very cheap clothes imported mainly from the US and Europe, which led to the downfall of the local textile industry in the early 1990s. In the 1980s the textile industry was Kenya’s leading manufacturing activity, employing about 30% of the labour force in the manufacturing sector.

Such collapses hindered investment in those industries, with dramatic results. Between 1991 and 1992, for example, the real annual growth rate of the manufacturing sector fell from 3.8% to a mere 1.2%, according to the World Bank.

New hope for Kenyan industry emerged in 2003, when Mwai Kibaki took over from Daniel arap Moi, who had been Kenya’s president for 24 years. Mr Kibaki soon unveiled the Economic Recovery Strategy for Wealth Creation and Employment (ERS). He hoped the plan would provide an environment for private enterprise to drive industrialisation. The ERS sought to improve infrastructure by increasing financial investment in roads, privatising railway operations and re-implementing infrastructure development plans that had been dropped under the previous government. It aimed to ensure that the rule of law was enforced.

While Kenya’s annual economic growth has since jumped from 0.5% in 2002 to an average of more than 5%, it is the burgeoning communications, financial services and retail sectors that have contributed to growth, not industry, according to the KNBS.

Two main reasons for this latest failure to stimulate industrial growth were also partly responsible for the failure of the export-promotion policies in the 1990s. First, policies have often been contradictory. For instance, in the early 1990s monetary strategy sidelined new export promotion programmes by targeting inflation and allowing extremely high interest rates on treasury bills. This made credit unaffordable to the private sector and manufacturing businesses—particularly small and medium-sized— struggled to expand.

The second main reason for the failure has been high-level corruption and mis- management. In 2005 the Centre for Governance and Development, a Nairobi-based non-profit research and policy firm, found that between 1992 and 2003, state-owned corporations—including the Kenya Ports Authority, the Kenya Railways Corporation and the Agricultural Finance Corporation—had “lost” more than $630m.

The post-Moi governments, for all their rhetoric about stamping out corruption, have not been sleaze- free. In 2003 several key ministers in Mr Kibaki’s government were impli- cated in the notorious Anglo Leasing tender scandal in which state contracts worth hundreds of millions of dollars were awarded to non-existent firms. In 2005 John Githongo, a journalist given a government post specifically to fight corruption, resigned, citing frustration with carrying out his job. Mr Githongo later accused several top-level ministers of fraud.

On the flipside, however, several moribund parastatals, such as the Kenya Meat Commission and the New Kenya Co-operative Creameries, have not only recovered, but have turned profitable.

Kenya is taking steps to remove these barriers to industrial growth. The country’s new constitution limits the number of ministries and defines their roles. In addition, the country is privatising state-owned corporations and has merged regulatory bodies to increase efficiency and reduce corruption.

Back in Nairobi’s industrial zone, a 250m-long strip of pitch-black tarmac stands out from the surrounding roads. Chogoria Road, once so badly potholed that it resembled the surface of Mars, now glints smoothly in the blazing Nairobi sun. Aside from fixing the road, the Nairobi City Council has also moved the car mechanics into lots off the road and set up kiosks for entrepreneurs to peddle spare parts.

Chogoria Road shows that it is possible for the industrial zone on the ground to match its promise on the map. Sustained political will and gritty efforts like this one need to be applied on a national level to make sure that industrial plans take root and grow, and do not remain good intentions neatly bound in policy documents.