Nearly a decade after the end of the bloody civil war in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), violence remains endemic. In one corner of the DRC’s infamous north- east, a large-scale mining project has built a public-private partnership to create a secure and prosperous environment for people and business.

Close your eyes and form a picture of the world’s most defiled war zone—a place where people and property are routinely hacked by pangas and aerated by AK47 gunfire. Chances are, you have the north-eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) in mind—Planet Earth’s violent, misbehaving urchin; the centre of War Inc’s blighted soul. Close enough to Rwanda to be singed by that country’s internecine conflict, and within range of Uganda and the infamous Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA), the north- eastern DRC is a version of hell, waiting for the perfect moment to explode.

Were you a geologist with a working knowledge of the world’s more prosperous gold deposits, the north-eastern DRC would blip on your radar for a completely different reason. The DRC is also renowned for its awesome mineral wealth that lies in some of the most inaccessible areas in Africa. Channel Islands-based miner Randgold estimates it to be worth two trillion dollars.

Take, for example, the copper and cobalt deposits in the south-eastern Katanga province. Administered by the parastatal Gecamines, and currently mined by numerous multinational players, Katanga Province’s copper fields offer a fascinating insight into the DRC. The area’s enormous geological wealth was for a long time hamstrung by a perceived lack of security. But today Katanga has emerged as one of the most stable regions in the country, as well as the most developed and receptive to private investment.

Katanga province confirms that private sector involvement in commodity ex- traction (not including oil) can lead to regional stability through public/private law enforcement cooperation, as unwieldy and occasionally dangerous as that cooperation may be.

In many respects, Katanga is the very tincture of an African backwater, policed by a combination of private security firms that have only the mining company’s interests at heart as well as an on-the-take military. Fealty is paid to the reigning Big Men, in this case President Joseph Kabila in Kinshasa, the DRC’s capital, and his Katanga mafia. Mining companies with sound corporate social responsibility (CSR) policies vie with old- school diggers who could not care less about local law and order. But rule of law and the protection of property are the two elements that underpin the capitalist system—no region can grow without them. While Katanga has been around for decades as a going concern, nothing provides more succinct an example of this truism than a pioneering gold mine in the north-eastern DRC, called Kibali.

The DRC shares the rapid growth rates of many sub-Saharan nations, with an estimated 2011 GDP of $15.7 billion and an anticipated $17.3 billion in 2012, according to the International Monetary Fund. With 67.6m people, the glass-half-full view of the DRC is as follows: were it to expand and become a middle-income economy, the opportunities for growth in every sector would be spectacular. But the country’s inherent volatility is inhibiting this possibility. The elections in December 2011, in which old political hand Etienne Tshisekedi challenged the results and violence flared up, reminded observers that political stability in the DRC is still a long way off.

One prevailing canard is that Kinshasa is the capital in name only and that President Kabila has a narrow band of influence, policing the presidential palace and not much else besides. But the government is a presence on the ground, even in areas as infamously contested as North Kivu and South Kivu where the United Nations’ (UN) peacekeeping programme in the DRC (MONUSCO) posts 17,000 pairs of boots. On a recent visit, influential Kabila special representative Kimbembe Mazunga made it clear to this reporter that the government ran the show in the region. He was especially eager to point out the new road that runs from Bukavu to Goma in the eastern DRC, built by Chinese engineering firm China Railway Engineering Corporation (CREC). Indeed, the government is obsessed with roads—Mr Mazunga continuously noted that during colonial times, the country boasted over 130,000km of traversable roadways. Now, that total is anywhere between 5,000 and 30,000km, depending on how one defines “traversable”.

Likewise, gauging the DRC’s stability depends on how one defines “stability”. In 2011, the DRC spent 2.5% of GDP on the military, according to United States Central Intelligence Agency figures. This is a seemingly low figure given the various armed factions that haunt the eastern and north-eastern provinces. (The LRA, while still a scourge, is little more than armed units of three or four men—bandits by another name.) The Armed Forces of the Democratic Republic of Congo, or FARDC, the main military organisation, is currently being rebuilt with the help of the UN, the European Union and a host of bilateral partners, including South Africa. Roughly 150,000 strong, the army is another inefficient civil patronage system among dozens. Real military power is devolved to the Republican Guard and other favoured regional units.

Nonetheless, and as far as Kinshasa is concerned, development depends on a confluence of infrastructure and might, which is another way of saying roads and rule of law. If Kinshasa is able to connect the country so that commodities can be transported easily, and guarantee the peaceful extraction of those commodities and their subsequent exportation, then the DRC has a chance at genuine progress.

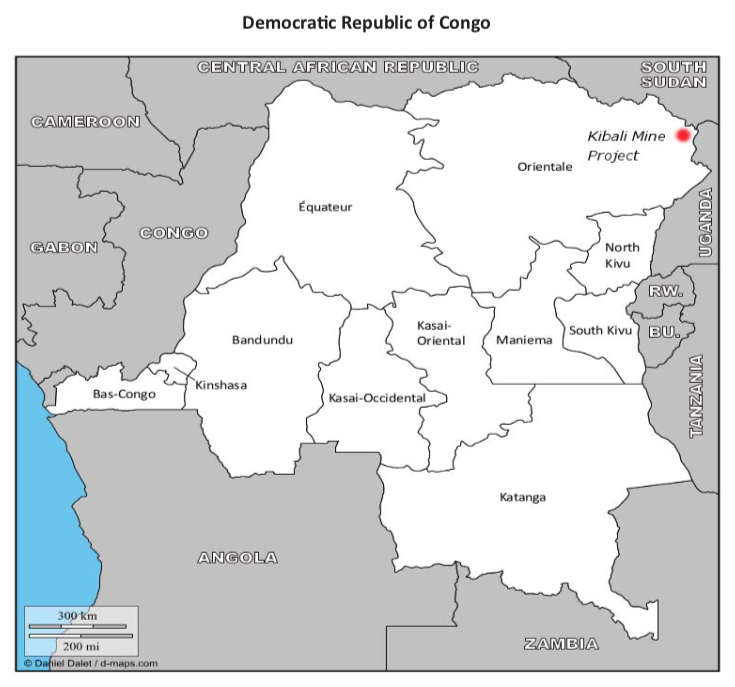

Orientale province, in the north-eastern DRC, is usually under-represented when the country’s natural resources are discussed. But, as the Belgians knew all too well, the area is particularly rich in gold. Canadian mining consortium Barrick Gold was one of the first to return to Kibali in the late 1990s following the collapse of the Mobuto Sese Seko regime, looking to prospect a so-called “elephant deposit” that stretched along the jungle ridges. Artisanal miners from local communities were chipping away at shafts abandoned by the Belgians, who had gone so far as to build a hydropower plant on the Kibali River in the 1930s, transporting the turbine through the jungle in an episode worthy of Joseph Conrad.

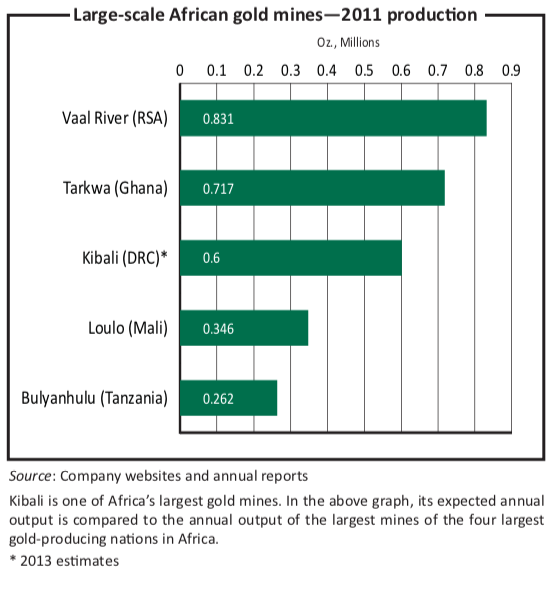

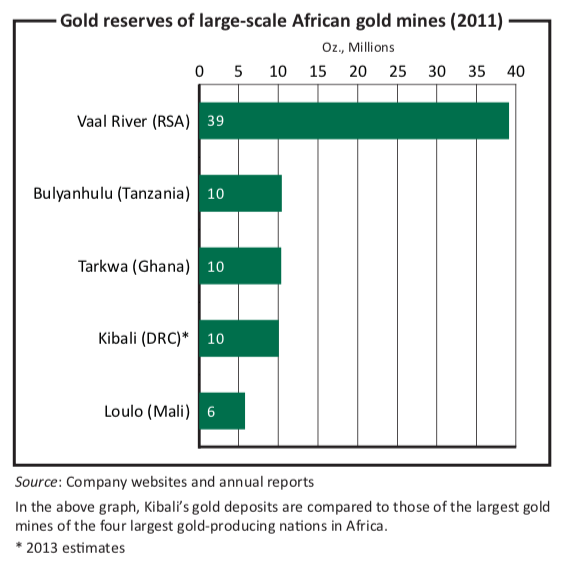

Located 560km north-east of the city of Kisangani, and about 150km from the Ugandan border, it was apparent that Kibali’s deposits were impressively rich, leading some commentators to compare the region to South Africa’s Witwatersrand (a claim geologists would scoff at). Barrick believed they were sitting upon 10m ounces of gold at the very least—Randgold’s recent estimates confirm the proven reserves at that amount, and indicate that it has an estimated additional 30m ounces. When civil war wracked the region from 1998–2003 at a cost of more than 5m lives, Barrick cited force majeure, locking up equipment behind a chain-link fence and leaving a company employee to guard it.

Barrick sold the mine to Canadian exploration firm Moto Gold, beginning a divestment process that now sees all of their African properties on the block. Moto continued to prospect, investing almost $100m in their operation. They in turn sold to Randgold and South Africa-based AngloGold Ashanti, which now own 45% each, along with DRC gold-mining parastatal Sokimo, which owns 10%. Randgold was to manage the mine, which was faced with serious—even fatal—infrastructure and security issues. The miners now had to justify to their shareholders an investment of half a billion dollars in an ostensible war zone and explain how they hoped to protect that investment.

The challenges appeared insurmountable. Artisanal miners were camped all over the site. Communities had to be forcibly removed or voluntarily relocated if industrial mining was to take place. These were not only logistical and human rights issues, but security issues: alienate the locals, and 17,000 enemies would surround the mine. Bring them into the fold, and presto: 17,000 allies.

Here, Randgold and AngloGold Ashanti’s commitment to CSR dovetailed with their need to secure the site properly. They entered into negotiations with Kinshasa and Orientale province, neither of which was likely to okay the forcible removal of the local communities. Tenure is a huge issue with mining companies in the country.

Louis Watum, the Congolese-born Kibali manager, had to put four measures in place. First, relocate the 17,000 people living on the mine site and build new housing, and in some case new towns. Second, offer the artisanal miners buyouts or alternative employment offers. Third, secure the Kibali site. Fourth, build the infrastructure necessary to get the mine running.

Every measure reinforced the next: it was easy to provide alternative economic opportunities if the road to Uganda was repaired; and if the area saw an economic boom, it was more likely to prove stable. The mine retained the services of two private security companies—one local and one multinational, about 80 men in all. It insisted that the guards not carry arms. “As far as we’re concerned,” said the Group General Manager for Operations in Central and West Africa, Willem Jacobs, “policing is the government’s job. We made it very clear to the authorities in Kinshasa that we would not supplement what we regard as the police or the army’s job. The second we have to pick up a gun, we’re out.”

The ploy worked, partly because the parastatal Sokimo was badly indebted to an individual Moto Gold shareholder and needed to develop the mine to pay off the debt. In other words, naked economic interests compelled the government to ensure adequate policing by a legitimate, properly trained (in relative terms) force.

Ironically, the job of policing became less of an issue the more the area developed. By the time Randgold completed the road to Uganda, 150km of graded and packed hardtop, a revival took place in Watsu, the district capital. Markets that once had a few measly stalls now enjoyed hundreds. Cheap Chinese and Indian goods flowed in from Uganda, along with “high-class” prostitutes from Kampala. To be clear, Kibali is a district that would happily exchange all-out warfare for the minor scourge of prostitution.

Several aspects make the burgeoning Kibali site unique. The first is the orderly removal and re-housing of 17,000 locals in homes built and paid for by the mining company—“the largest operation of its kind in African history”, according to Mr Watum. The second is the opening of a gold mine that will cost upwards of $700m in an area that has arguably the worst reputation in Africa outside of Darfur in western Sudan.

Randgold and AngloGold Ashanti are not responsible for the people of Kibali or the future of the DRC. Their primary responsibility is to their investors and shareholders. That said, enlightened self-interest dictates that a happy region means a quiet region. This explains their investment of more than $200m in housing, roads, dams and other infrastructure that promotes this objective.

In turn, impetus from the private sector has sparked the government to improve law and order. The road from Uganda means that troops can be moved more freely. Money for policing is now flowing into Orientale coffers, a scenario that the region’s biggest cash cow—the mine—insists upon.

As big as Kibali is in mining terms, it influences only a tiny sliver of the DRC. But while the Goma region, with its 17,000 UN representatives, has a big security problem, Kibali does not. It is proof that the private sector can incrementally im- prove law and order, even in a country as difficult as the DRC. When companies replace short-term profit-seeking with enlightened self-interest, they can give true meaning to the term “development”.