Africa’s longest-standing monarchy sidestepped the Arab Spring.

by Larbi Sadiki

Morocco’s kings have perfected the art of simulating change while ensuring that things stay the same. This smoke and mirrors act has enabled this North African monarchy to maintain its stranglehold on power for centuries and most recently to adapt to the Arab Spring’s winds of change.

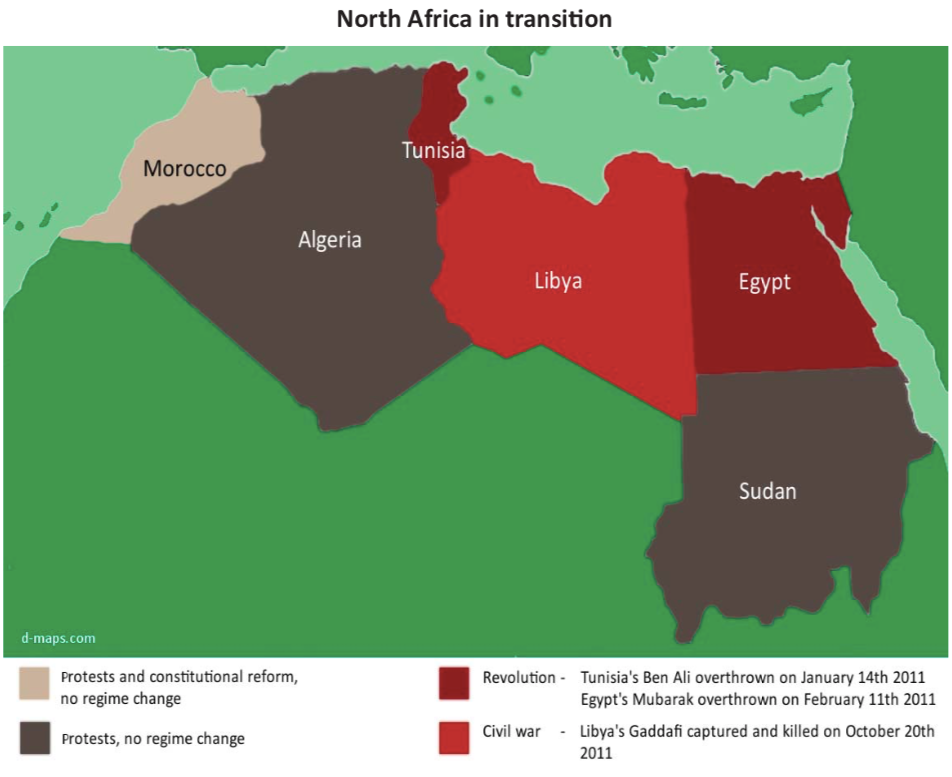

Mass demonstrations in the Arab Maghreb, first in Tunisia in December 2010, followed a month later by Egypt and then Libya, led to the toppling of long- time dictatorships. Protests for political equality and participative governance also hit Morocco. But here, by comparison, little has changed. The young king, Mohammed VI, 49, managed to survive the protests that engulfed his country, proving himself to be an astute political animal.

Mohammed VI remains regal in every sense of the term. Islamists and secularists, elected or non-elected, revolve around him as the fulcrum of power. The king, one of the richest men in Morocco, calls the shots in religious, security and economic affairs. It is a game of concentric arenas of power: in theory the prime minister runs the government, and to an extent he does; but he presides over cabinet and the country’s security council by following agendas scripted by the king.

Mohammed VI protected his throne from an infectious Arab Spring by reconfiguring the political stage through a carefully calibrated reform agenda. In the process, Morocco reaped dividends of political and economic stability.

The king maintained his grip on power in two distinctive ways.

First, he strengthened the legitimacy of the monarchy—a prescient move that he began even before the Arab Spring—thus allowing the kingdom to absorb the shocks of popular and global pressure for change. Second, he promoted the opposition to government and demoted to opposition the parties he had partnered with in the past.

Mohammed not only knew how to respond swiftly and on his own terms to the challenges posed to his reign by the Arab Spring. More importantly, he anticipated them and worked to reform his rule years before unrest erupted in the Maghreb.

In 2004 the king established the Equity and Reconciliation Commission (IER). Though it, he sought to distance his rule from that of his father, King Hassan II. The IER’s mandate is to expose human rights abuses and cases of torture and oppression under the former ruler.

Under Mohammed VI’s rule, Moroccan society has also experienced greater freedom of expression. In 2003, the Mudawwana, another piece of legislation, equivalent to a personal status code that governs family jurisprudence as well as women’s rights, was made law after initial Islamist opposition. It gives women protection against male abuses, including unilateral divorce.

Protests for more rights and freedoms that hit Morocco in early 2011 were a signal that the monarchy needed to up its game. In July 2011 a referendum, strongly endorsed by the public with nearly 98% of votes in favour, brought constitutional reforms which diminish the king’s powers and grant the government executive power. For the first time in Morocco’s history, the prime minister appoints government ministers and is empowered to dissolve parliament. Both were previously strictly royal prerogatives.

To some extent, these changes have increased the Moroccan monarchy’s political legitimacy. They have allowed it to engineer its own version of the Arab Spring and keep centrifugal forces in check, for now. To those who have accepted the monarchy’s reforms, some change, even if it comes from the top, is better than none.

The parliamentary multiparty polls in November 2011 also helped to diffuse unrest. In a stunning political turnaround, the moderate Islamist Justice and Development Party (or PJD, after its French initials) scored a resounding victory. It was unprecedented in the country’s 30-year history of largely cosmetic elections. The Islamists more than doubled their share of seats, increasing the total to 107 from 46 in the 2007 polls.

To many, the PJD’s victory has the potential to upset the balance of power and could usher in the kind of “revolutionary” change neither the monarchy nor a measurable segment of the secular parties loyal to the monarchy would like to see precipitated at this historical juncture.

The party’s dynamism and hard campaigning before the election partly explains the result. But there is also an element of contrivance. The PJD was given an opportunity to participate while the king banned other Islamist parties: notably the Justice and Charity Party, considered Morocco’s biggest opposition force.

Lifting Islamists to power makes sense in the regional context. Islamists are on the rise throughout North Africa. In Egypt and Tunisia, they have proven that they command wide support and enjoy popular appeal.

By facilitating the political ascent of Islamists, the king mimicked the revolutionary rise of Islamists in post- revolution North African neighbours and prevented further revolutionary upheaval at home. But popular choice did not govern which Islamists made it to the top. The rise of the PJD only occurred with the approval of the king. His support broke with Morocco’s history, which permitted secular parties such as the Istiqlal (Independence) to serve as loyal partners of the monarchy and dominate parliament.

Constitutional reform and the rise of the PJD have placated much political discontent. But this redrawn government-opposition map is informed by a modus operandi through which Mohammed VI, as during his father Hassan II’s reign, defines the terms of the political game, demarcates its boundaries, and controls the pace and scope of reform. He remains head of the army, religious bodies and the judiciary. For this reason and others, the February 20th protest movement boycotted the July 2011 referendum and rejected the constitutional reforms.

The ceiling of monarchical reform in Morocco can never measure up to the high aspirations of the new protest movement and the urban youth, who are eager for inclusiveness in politics, economy and society, despite facing threats of coercion and detention.

Some, who first welcomed the developments in Moroccan politics, have since come to the realisation that the changes were largely cosmetic. In May 2012 angry protestors filled the streets of Casablanca, ironically accusing Morocco’s prime minister, the PJD’s Abdelilah Benkirane, of failing to deliver on promised reforms.

The Bloc for Democracy, an alliance made up of eight parties, including two which partake in the governing coalition, have coalesced to ensure the opposition is dynamic in the new parliament, where the winning Islamic party has wider powers than under previous administrations before the July 2011 referendum.

Mr Benkirane has more power than his predecessors. But with or without Mr Benkirane’s consent, the king has used his party as a pawn to ride out the popular protests that hit Morocco. Now that the height of the Arab Spring has passed, the protest movement is divided and weakened, and the threat of revolution has diminished. In September 2012 the king bypassed Mr Benkirane by ordering the arrest of 130 allegedly corrupt customs officials working in Tangier’s port. This effectively renders null and void the constitutional reforms passed in July 2011 while strengthening Mohammed VI’s grip on power. Perhaps even more worrying is how easily he has managed to co-opt the opposition and made it dance to his royal tune.